Photography courtesy of the Dallas Municipal Archives.

NOVEMBER IN DALLAS is known for other things, but the 11th month also marks a maritime disaster and the arrival of German war prisoners.

Each November, the somber anniversary on Dallas’ collective mind is that of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, which to many remains one of the most devastating events of the American 20th century.

It is little wonder that our city’s inhabitants don’t dwell much on other events of Novembers past. Yet a few forgotten happenings are worth recall.

Here in the White Rock Lake neighborhoods, the 11th month marks milestones including the sinking of the Joe E. Lawther, the arrival of captured war prisoners and an oil tycoon’s purchase of Dallas’ larger replica of President George Washington’s Mount Vernon, to name a few.

November 1937: Sinking of the Joe E. Lawther dredge boat

Every 18-20 years, buildup of lake-floor sludge necessitates an expensive undertaking that involves excavating excess sediment and debris using massive vacuum-like machinery.

The inaugural White Rock Lake dredging launched Nov. 5, 1937, and involved a craft worth more than $6 million in today’s money. Likely considered unsinkable as it left its port on the northeast side of the pond, the vessel would, within a few days, become ensnared in one of our burg’s costliest maritime disasters.

White Rock Lake was in its mid-20s when buildup began causing offensive odors and unsanitary conditions, explained a report by Civilian Conservation Corps, a contingent of young Americans and their officers, who, following Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, had been working the previous two years to transform the park into the urban oasis we know today.

Relentless Texas sun caused rapid evaporation in the northeast creek, where hundreds of trapped fawning fish died and rotted, according to the report. It was not a good look, or smell, for a Dallas attraction then riding a reputation as The People’s Playground, with all of its private fishing cabins, dance pavilions and speedboat racing.

The report proposed “reclaiming shallow marshlands that had formed at the mouth of Dixon’s Branch,” the creek that flows into Sunset Bay, which at the time was called Dixon Bay, author and Dallas historian Sally Rodriguez says. She clarifies, “Sunset Inn overlooked Dixon’s Bay and at some point it mutated to Sunset Bay.”

To do the job, the City of Dallas procured a $31,973 shallow-draft hydraulic boat and called it the Joe E. Lawther for the former mayor who championed park preservation. Although slated to begin Sept. 15, the effort did not get underway until Nov. 5, and at 8:30 p.m. Nov. 17, Lawther sprung a leak, sending crew members Jesse Perkins and F.H. Luttrell “scrambling to escape” as the craft sank into six feet of water, as told in the text, Legacies: A History Journal for Dallas and North Central Texas.

“This book has a colorful way of describing Dallas’ history,” says Rodriguez before reading passages about the ill-fated voyage aloud.

“At first no one was sure who to blame for the accident. For a while it was rumored drunken CCC workers were at fault, a story that proved unfounded. After W. J. Redman, a professional diver from Galveston, refloated the Lawther, it was discovered that manufacturing defects, including a lack of hard timbers to overcome vibration of the engines caused four leaks in the hull.”

Later that winter, the Lawther was repaired. The dredging resumed and eventually reclaimed nearly 90 acres, 20 at Dixon’s Branch and 68 at the northern end. CCC and City workers used some 500,000 tons of removed silt, according to City of Dallas archives, to fill marshy areas around the lake.

The last dredge was in 1998, and another is expected following a feasibility study, which was approved last year and is underway to determine project goals, risk factors, possible alternatives and associated costs.

November 1937: Purchase of Mount Vernon, White Rock Lake version, for $69,000

While Texas oil tycoon Haroldson Lafayette Hunt Jr. — more commonly, H.L. — did not move his family in until New Year’s Day 1938, he purchased Mount Vernon on White Rock Lake in November of the previous year, records show.

According to a 2010 Forbes article, H.L.’s youngest son, Ray Lee Hunt, inspired the creation of the TV show Dallas and J.R. Ewing.

The elder was a character in his own right. He and his first wife Lynda Bunker shared Mount Vernon with their seven children. Texas lore holds H.L. married his second wife Frania Tye before Lynda’s death, and they had four children. H.L. and his secretary Ruth Ray, whom he married following Frania’s demise, had another four.

In 1999, Lakewood resident Robert Barnett, who built his family’s home in 1926, told The Advocate about his encounter with the Hunt household in January 1938.

“My horse, Firecracker, ran away. I got on my bicycle and started riding around the lake searching for the horse. I finally found him grazing on the lawn of a family just moving into their new house overlooking the lake,” Barnett recalled.

It turned out to be his only encounter with the owners of the mansion modeled after George Washington’s Virginia estate. Its facade does not look much different today than it did back then, but owners over the years have renovated the interior.

November 1944: POWs come to town

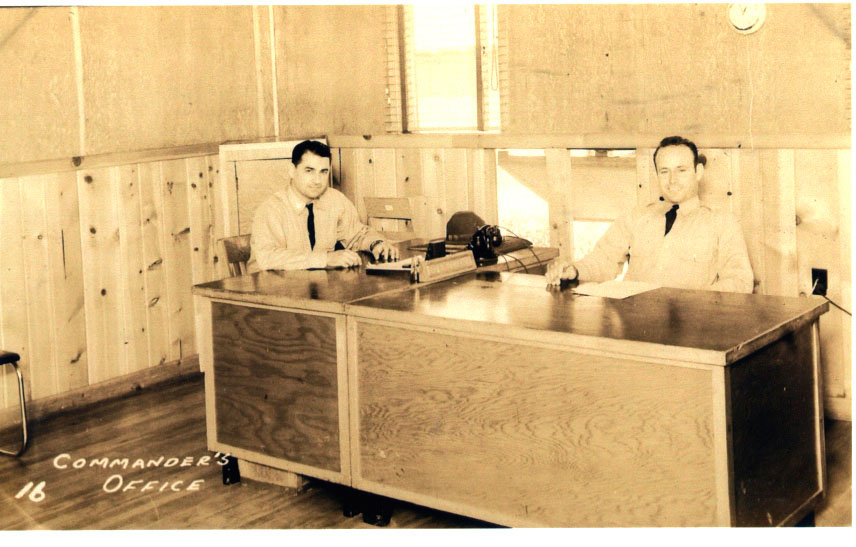

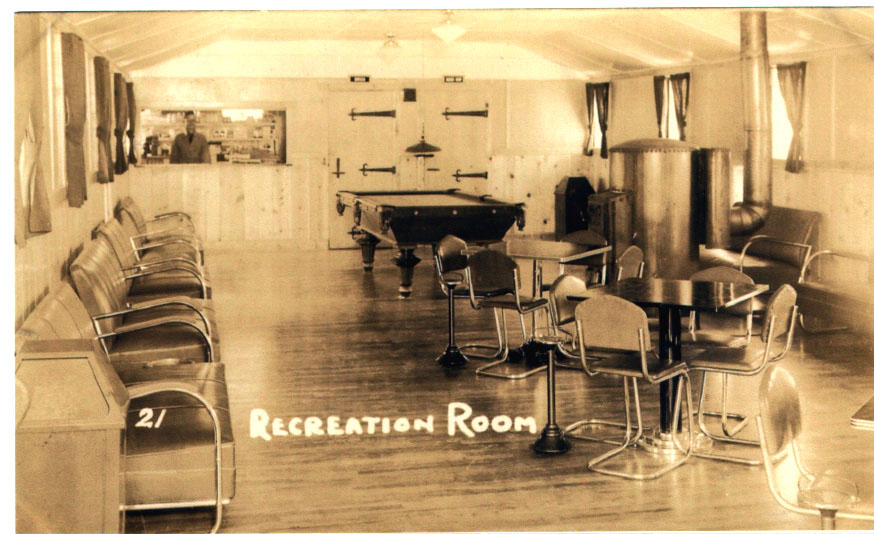

On Nov. 20, 1944, 300 skinny, sunburnt, battle-beaten, khaki-clothed veterans of the German Africa Corps rolled into East Dallas and set up camp among the White Rock CCC’s unoccupied wooden barracks.

American workers no longer needed the beds, after all. Pearl Harbor meant the end of that particular park-improving program, as all the able-bodied young men joined the war effort.

The new arrivals hailed from Hitler’s prized expeditionary force in North Africa, which fell to Allied forces in spring 1943. The United States took 400,000 of these POWs, and 200,000 came to Texas.

Mexia, a Hill Country town of 6,000 at the time, received more than 3,000 prisoners, notes author and historian Ronald H. Bailey, who described townspeople lining up to watch the captives detrain, wearing “large bill-cloth caps and goggles that symbolized Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s infamous Afrika Korps.”

A total of 403 of the Mexia prisoners relocated to White Rock. Each afternoon during the Mexia camp’s 11-month tenure, the internees rode a bus to work at the Dallas Regional Quartermaster and Repair Shop at Fair Park, where they mended clothing and equipment.

“In one large room ventilated by three six-foot-high wall fans, 95 men sit at sewing machines repairing G.I. uniforms,” according to a 1940s Dallas Morning News article.

Geneva Convention rules afforded even Nazis humane conditions — Texas was a popular locale for POWs due to its climate, which would save the War Department on heating bills and keep prisoners comfortable. Rules allowed POWs to work, provided the labor did not relate directly to the conflict and was safe.

Dallas historian and author Sally Rodriguez describes the prisoners’ first order of business.

“Upon arrival, they constructed their own enclosure, an eight-foot tall barbed-wire fence around the camp’s perimeter, because there was no fence, no need for a fence, before,” Rodriguez says.

She says the prisoners enjoyed relatively pleasant conditions and had no ostensible reason to abscond or rebel. In fact, she points to an interview with the era’s Park Director L.B. Houston, who considered many of them “artisans.”

In Houston’s transcript, the late director discusses how “artistically inclined” and “brilliant” the POWs appeared.

“They developed stencils and stenciled a mural around the walls, you know, flowers and animals. It was really an attractive place. They had gardeners. They wanted seeds, which we furnished. They made it a real attractive place,” Houston said.

Neighbors in the 1940s were, as now, concerned then with lake-area goings on, to the extent that one could be during wartime. In fact, at one point the army wanted to use these same barracks as a medical facility to treat women with venereal disease who were associated with, or “followed,” American soldiers, Houston explained.

“You can imagine how unpopular that thought was to the people of Lakewood and Dallas generally,” Houston said in the transcribed interview. “That argument ended shortly with the army deciding not to use it for that, but they did assign it to the Fifth Command. A lot of men, young men, right in the Dallas area, were inducted and did their boot training right at that location out there at White Rock Lake (prior to the POWs).”

As for the later military use for captured Nazis, Houston reported, “If you drove by outside, if you just looked through the barbed wire and saw men in there, you probably wouldn’t have realized what it was.”

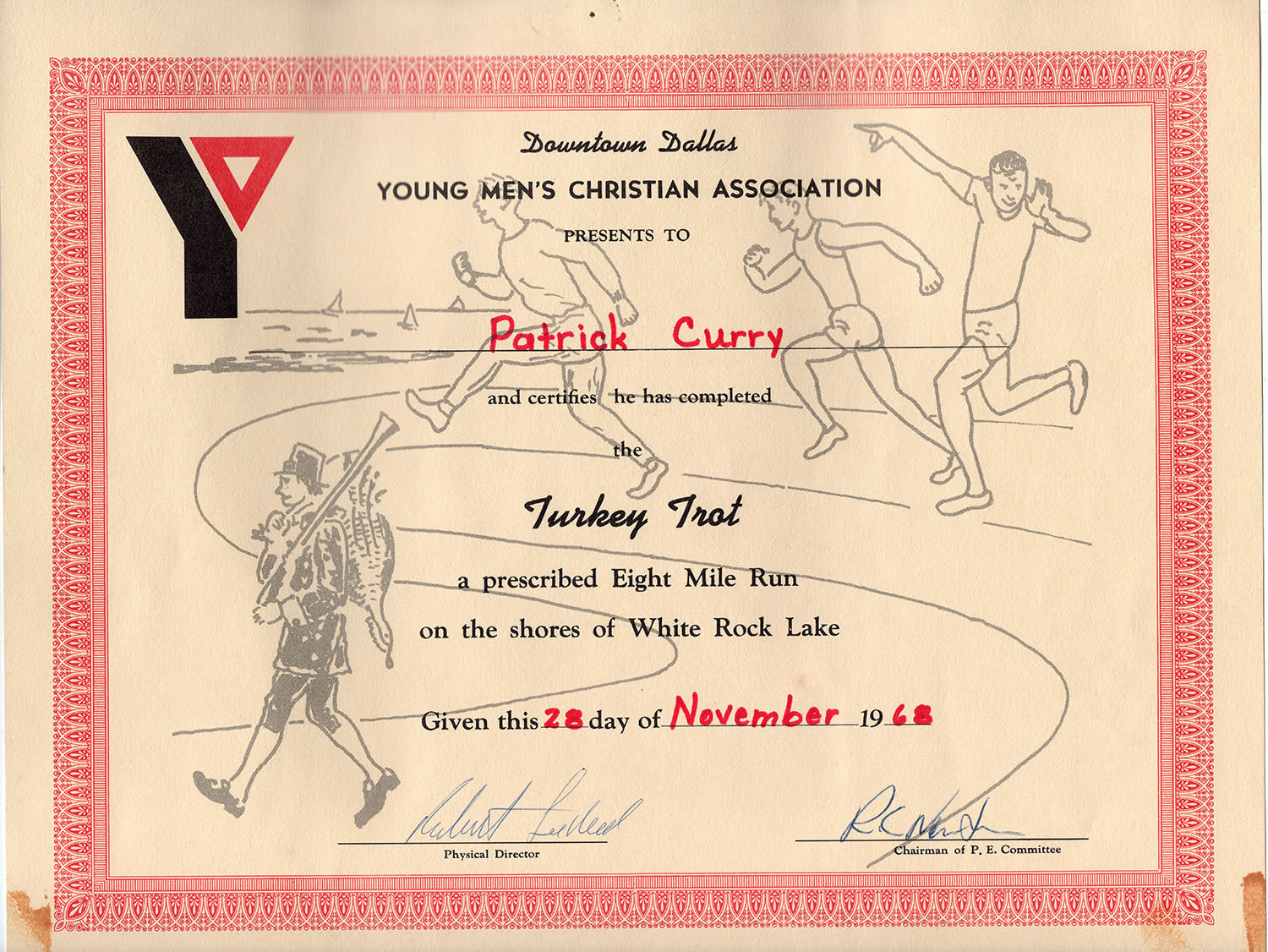

November 1968: The Turkey Trot becomes Thanksgiving tradition

It was a cold morning, temps in the low 40s, ideal by runner standards. The Cowboys would play the Redskins that afternoon, but first, 107 competitors toed the line at the first official Dallas Turkey Trot at White Rock Lake.

A tradition at Fair Park throughout the 1920s and 30s, Dallas dropped the event during the Depression, and the Park Board revived it Nov. 28, 1968.

Ralph W. Trimble and Nancy Norvell won the men’s and women’s races respectively that Thanksgiving, and all finishers earned a certificate showing “completion of a prescribed eight mile run on the shores of White Rock Lake.”

Today the race, which relocated to City Hall in 1979, draws more than 40,000 entrants and is tradition for many Dallas families. Old news clippings indicate it’s always attracted competitive broods. A 1970 Dallas Times Herald article by Steve Israel profiled the Buckinghams — mom, dad and six adolescent children — who reportedly trained together and were known to take division awards. The previous year, all eight took home trophies in their respective age and gender groups.

Also in the race’s third year, 29-year-old Miki Hervey, later Miki Snell, a Braniff airline hostess, won the women’s race. Years back, she told The Advocate it was at that Turkey Trot on the White Rock Lake trail that she met her husband, the famous New Zealand Olympian turned Dallas doctor, Peter Snell.

A newspaper article notes that Hervey, winning again the following year, was a crowd favorite.

The couple was married for 36 years until Peter’s death in 2019.

Sally Rodriguez’s books White Rock Lake (2010) and White Rock Lake Revisited (2014) are available through Arcadia Publishing, arcadiapublishing.com.

Timeline of Novembers past

Nov. 15, 1910

Seven workers were injured in a derrick accident at the White Rock Lake dam construction site. City Archivist John Slate says the City of Dallas planned the reservoir as a municipal water source and many of the historical photos of its construction were taken in the fall of 1910. White Rock Lake was established in 1911.

Nov. 5, 1937

A boat named for Dallas Mayor Joe. E. Lawther began and ended a few days later in a costly maritime disaster.

Nov. 17, 1937

Oil tycoon H.L. Hunt purchased Mount Vernon, a replica of George Washington’s estate, on the shore of White Rock Lake, for $69,000 — the equivalent of about $1.3 million today. He moved in with his first wife Lyda Bunker and their seven children early the next year.

Nov. 5, 1944

Three hundred prisoners of war arrived at the army barracks located near Winfrey Point where they lived for almost a year.

November 1968

The inaugural Thanksgiving Day Turkey Trot involved 107 competitors who raced 8 miles along the shores of White Rock. In 1979, when the event became bigger than the lakeside park could bear, the Dallas Park Board relocated to City Hall.