Photography by Julia Cartwright.

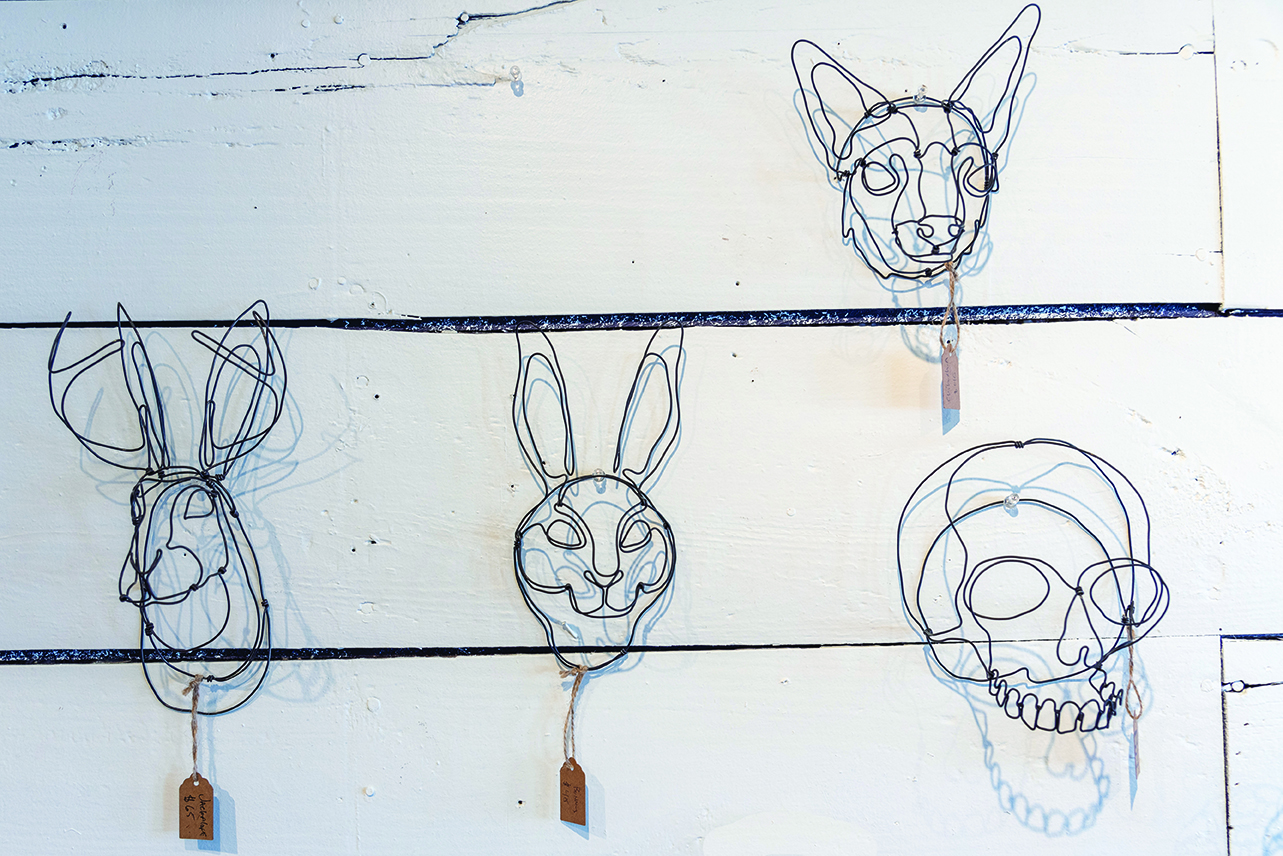

It was an unseasonably warm November day, and the open-air market at Greenville and Oram was packed with people. Among the vendors offering all sorts of wares, like custom skateboards or homemade hot sauce, there was a tent filled with wire sculptures of animals.

Maxwell Rasor, the man who made the sculptures, sat at the back of the tent, twisting a bird into life with a pair of pliers and looking just as wiry as his creations. He sat the bird down every time people stopped by the tent in order to greet them. His hands were stained black from the oil coating the wires, so handshakes were out of the question, but he offered every guest a wave and a hello. Then, he waited patiently to see if they had any questions about the art.

Here are the answers to the most common ones: Each sculpture takes about an hour to make, maybe longer if it’s particularly detailed. Birds and fish are the most popular with customers, because sporadically people will recognize their favorite species. Dogs are a popular choice, too, but Rasor says that a lot of the dogs he makes are by commission, so customers can receive a sculpture based on the likeness of their own pet.

One of the other common questions is how Rasor conceptualizes each creation in a 3D space. That question is trickier to answer, because it comes to Rasor naturally. But part of it is because he’s been making sculptures for almost his entire life.

“My dad was a sculptor growing up, so I was always kind of into it,” Rasor says. “I kind of grew up sitting in his lap with him bending wire right in front of my face, and it just kind of caught on.”

Rasor was born and raised in Oak Cliff, and he made his first creations when he was about 6 years old. That is also about the same time his father stopped sculpting; Rasor’s parents got a divorce, and his father had to focus on being a single parent. But Rasor never stopped, and he attended W.E. Greiner and Booker T. Washington for middle and high school to keep honing his artistic skills.

After high school, he moved with his then-girlfriend Ariel Reno, who is now his wife, to Austin. They moved around Texas as Reno, who designs prosthetics, completed residencies. Her last residency was in San Antonio, and when she completed it, she received a job offer in the city. A few years later, she gave birth to the couple’s first child. When Reno returned to work, Rasor would stay home to watch their son, but he continued to sell his artwork, too.

“My wife is definitely the breadwinner in our family,” Rasor says. “She was like, ‘I can make more money than you can, but make what you can.’ And I do. I watch the kid and save cash and make sure he is learning how to read.”

Then, when their son was a few months old, the COVID-19 pandemic began.

“And so I spent two years just making stuff,” Rasor says. Rasor and Reno moved to East Dallas in October 2021 to be closer to Reno’s parents.

“I think the pandemic changed everything here,” Rasor says of Dallas’ art scene. For example, before he moved away, there were few vendor markets. “When I got back to Dallas, they were just all over the place, which is just awesome.”

In addition to the vendor markets, Rasor says there’s a strong network of artists involved in various collectives around the city, and galleries will occasionally do open calls in order for local artists to showcase their works.

For Rasor, the biggest challenge to being an artist is not selling his works, but finding time to make them. His first priority, of course, is raising his son. Reno is pregnant with the couple’s second child, and Rasor knows a second kid will make life even more hectic.

“Just having a 3-year-old, he eats up 90% of my time. I have about an hour and a half that he takes a nap where I can work quietly,” Rasor says. Then, when Reno gets home, the family has a sit-down dinner and spends time together until Reno and their son go to bed.

“Then I start working again. I work until the late hours in the night, and then I go to sleep, and I don’t get enough sleep, and then I wake up at 7 o’clock all over again.”

But when I asked if Rasor still finds his work rewarding despite the stresses associated with it, he didn’t hesitate to answer.

“Oh, yeah. I would never be in a situation where I couldn’t make stuff all the time,” Rasor says. “I am, at my core, a maker.”

Rasor’s home is filled with his artwork. Not just his wire sculptures, but other creations, like wind-up automatons and kaleidoscopes. Rasor doesn’t usually make anything that he wouldn’t display in his own house, which is a good thing, because that’s where he keeps most of his artwork before he takes it to market.

“If I didn’t have to, I wouldn’t sell anything that I make,” Rasor says. “I would just give it to people if I wouldn’t get in trouble for it. But I have to pay the bills.”

He sees his love of creation reflected in his son.

“My kid is already like a little builder guy,” Rasor says. “Like, I can barely give him toys. He’s just taking them apart immediately, because he (has) spent the first two years of his life watching me cut wooden cogs out.”

Rasor’s creations are best enjoyed in person. If you ever get the chance, be sure to stop at the Underground Market, which is held every Sunday at Greenville and Oram, and look for the wiry man with his palms stained black.