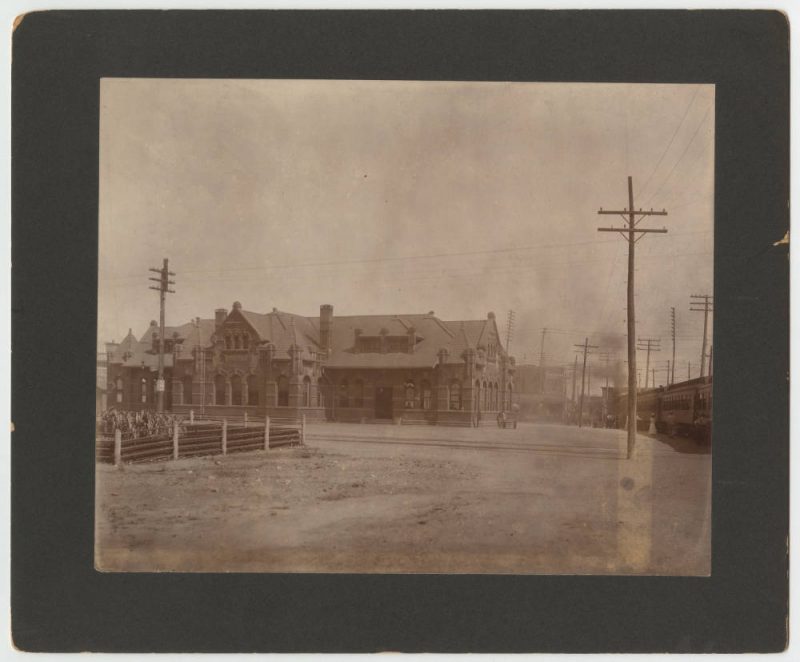

Photo of the old Union Depot, courtesy of Flashback Dallas.

It was Dallas in the late 1800s. Post-Civil War rebuilding had begun, and the city’s leaders had a plan to grow the economy. They knew the railroad was the key. With the help of former Confederate army officer and landowner William Henry Gaston, they convinced the Houston & Texas Central Railroad to build its northward expansion closer to the city than originally proposed.

Preparation began. Trees were cleared, and the major east-west streets — Elm, Main and Commerce — were expanded. The first trains roared through the city in 1872. People and businesses followed.

Within a year of the railroad’s arrival, 750-900 buildings were constructed. The population increased to more than 10,000 in 1880 from 775 in 1860.

Without the railroad, Deep Ellum wouldn’t be the loud, lively place it currently is. But a look at the neighborhood today won’t reveal everything about its past.

Shortly after the railroad arrived, the area that became Deep Ellum included agricultural fields, restaurants, lodging houses, variety theaters and saloons. Freed slaves formed a community north of downtown, near the intersection of Thomas Avenue and Hall Street, called Freedmantown. They settled and set up businesses along the railroad in an area known as Central Track, which divided Deep Ellum from downtown. By the early 1900s, Central Track was populated mainly by Black communities, while Elm Street was populated mainly by white people.

Deep Ellum’s reputation as an epicenter for music and entertainment dates to the 1890s. Businesses such as the Black-owned Black Elephant vaudeville theater were popular by that time, but the city’s tightening regulations forced it and others like it to close. However, Black-owned theaters rebounded during the first few decades of the 20th century.

Those theaters in Deep Ellum catered mostly to Black audiences, though they also welcomed white visitors. The Tip Top dance hall, located on the second floor of a former railroad hotel, was one of the popular spots during the 1920s. Musicians including T-Bone Walker played on the weekends for customers shopping at the downstairs tailor shop.

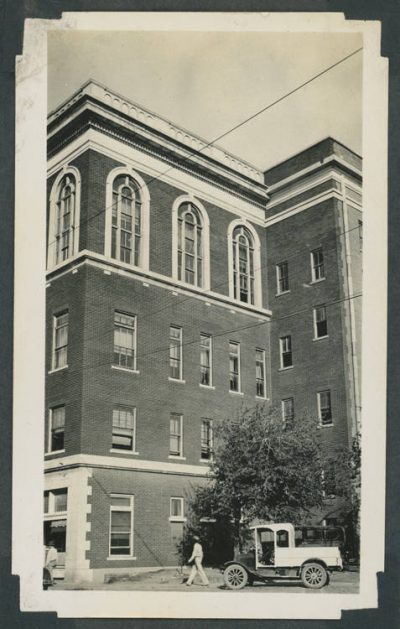

The Knights of Pythias Temple. Photo courtesy of the George W. Cook Dallas-Texas Image Collection at SMU.

Some of the city’s historical buildings were erected after the turn of the century. In 1916, architect William Sidney Pittman designed the headquarters of the Grand Lodge of the Colored Knights of Pythias on the 2500 block of Elm Street. The building was the site of a 1922 speech by Marcus Garvey. The next year, George Washington Carver demonstrated sweet potato products there.

The success of musicians such as Blind Lemon Jefferson prompted other blues and jazz artists to flock to Deep Ellum in the 1920s and 1930s, searching for work.

Deep Ellum was a hub for small businesses, many owned by Jewish immigrants who arrived by trains. These shopkeepers were, in general, kind to the Black community. They welcomed them into their stores and let them try on clothes, something not allowed downtown. Many business people were pawnbrokers who lived in South Dallas. Their shops included Uncle Sam’s Pawn Shop, Rocky’s and Honest Joe’s, all on Elm Street. Another Deep Ellum establishment was The Model Tailors, which clothed everyone from George “Machine Gun” Kelly to civil rights leader A. Maceo Smith.

After decades as a thriving entertainment and commercial district, Deep Ellum began to change in the 1950s. Small businesses closed when they lost customers to malls. The Great Depression had quashed peoples’ entertainment budgets. And as integration efforts were implemented and the possibility for upward mobility emerged, some Jewish and Black families moved.

Source: Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, by Alan Govenar and Jay Brakefield, 2013

Rock ’n’ roll originator T-Bone Walker, who grew up in Dallas and got his start in Deep Ellum. Photo courtesy of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.