When Madison Bishop enrolled in the International Baccalaureate program at Woodrow Wilson High School, she knew the rigorous coursework would pay off with a high class rank that would practically ensure her acceptance into the most prestigious universities.

As she spent hours poring over literature homework that didn’t interest her, she realized IB wasn’t the right fit. She was drawn to science and math and knew she would thrive in the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics program.

She quit IB in favor of STEM, knowing that her class rank would plummet.

That’s because, at Woodrow, class rank and the IB program are inevitably intertwined. In 2018, individuals enrolled in the IB program made up 63 percent of the top 10 percent of students. That number grew to 88 percent in 2019, even though IB students made up only 17 percent of the student body, according to Dallas ISD data.

District officials say unequal representation in the top 10 percent shows how difficult it is for students in Woodrow’s other advanced academic programs to graduate at the top of their class and gain automatic admission to the state’s flagship universities.

In August, DISD implemented a new class rank system that is intended to level the playing field across all academic programs, including IB, STEM, Advanced Placement and dual credit.

The problem, some IB parents say, is that leveling the playing field slapped their kids with a penalty.

A RETROACTIVE REVAMP

Under the old system, rank was calculated based upon students’ grades in their top 24 credits, regardless of subject or academic program. District officials say that prompted some students to boost their rank by taking “easy” electives in challenging programs, whose classes are heavily weighted.

Under the old system, rank was calculated based upon students’ grades in their top 24 credits, regardless of subject or academic program. District officials say that prompted some students to boost their rank by taking “easy” electives in challenging programs, whose classes are heavily weighted.

For example, a student taking dual credit P.E. at community college would get more credit than a student who receives the same grade in general education P.E. at Woodrow.

The problem is that dual credit courses are not offered on the Woodrow campus. Some dual credit courses cost an average of $330, district officials say, and students who can’t afford to pay do not have the same opportunities to boost their rank.

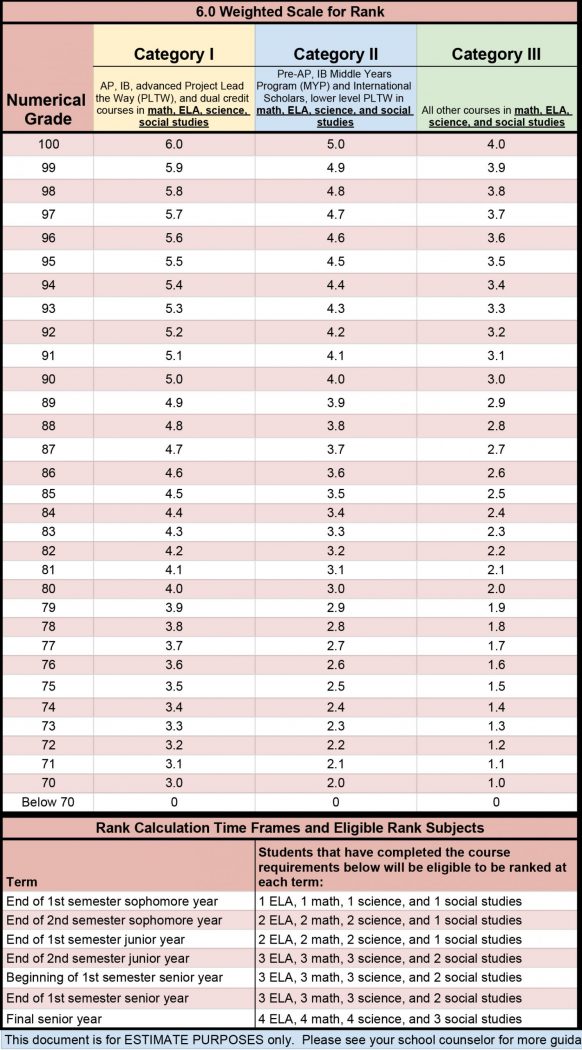

To create a more equitable system, rank will now be calculated based upon a student’s performance in 15 core classes that everyone must take to graduate. Eligible courses in math, science, English and social studies are assigned to three categories based upon their level of difficulty, and grades are converted to a 6.0 weighted scale.

Several school districts, including Plano, Frisco, Carroll and Wylie, have made similar policy changes to reduce GPA chasing. Although those districts implemented their policies with incoming freshmen, at DISD, the new rank system is in effect for the junior class.

For parents like Lakewood mom Michele Matney, the fairness of the new system isn’t the problem. It’s the fact that it’s being applied retroactively.

“The bottom line is, you can’t come in junior year and say, ‘We’re playing by a different set of rules,’” she says.

Although Matney’s daughter—who graduated from Woodrow in 2019—would have benefited from the policy, the same can’t be said of her son, a junior enrolled in the IB program. He was counting on IB and AP classes to boost his class rank. When the new system was unveiled, he discovered his advanced electives in foreign language and other subjects wouldn’t count.

Matney’s son suffered another blow when district officials counted his eighth grade math class toward his class rank. Parents see this as another flaw in the system, considering that students from various middle schools with varying educational standards can transfer to Woodrow.

“In eighth grade, my son was 13 or 14 years old,” Matney says. “The mindset is that if you have a C in math, it doesn’t matter now, but next year, everything you do will matter. I would have had a much different mindset with my kid.”

Although DISD officials recognize the concern, “our various academic programs necessitate that the policy become effective immediately to ensure all students have the opportunity to compete with their classmates, regardless of their pursued program of study,” says Ivonne Durant, the district’s chief academic officer.

Waiting to implement the new system would “allow the inequities in the previous rank system to exist for an additional five years,” she says.

THE IB ISSUE

Elizabeth Furrh, president of the Woodrow IB Parent Organization. Photo by Danny Fulgencio.

Although students in other advanced programs may be negatively impacted by the class rank change, much of the outcry has come from Woodrow IB parents.

What is it about the IB program that seems to catapult students into the top 10 percent? One theory is that IB curriculum requires juniors and seniors to take six of the hardest courses in each of their final two years. Whereas a STEM student, who excels in math and science, might take advanced courses in those subjects but opt for lower-level classes in English and social studies.

“If you’re an IB student who hates math, too bad. You have to take IB math. You don’t have a choice,” says Lakewood neighbor Elizabeth Furrh, president of the Woodrow IB Parent Organization. “You can’t expect to take [only] two or three hard classes and compete because there are some students who take the highest-level classes the moment they walk in the door.”

To complicate matters, Woodrow IB parents have had a rocky relationship with DISD over the past year.

In May 2019, just days before graduation, some students received a new class rank because of a DISD administrative error that doubled the number of credits awarded to some IB courses. Then in recent months, parents opposed district changes to the IB application that they say could threaten the program’s existence at Woodrow.

Although Hillcrest High School has an IB program, Woodrow is the only DISD school with IB graduates. Therefore, it must consider applicants from across the district, per regulations from the international IB organization. But in December, the district cited overcrowding at Woodrow as the reason for restricting the IB application to students within the school’s feeder pattern.

After school board trustee Dustin Marshall intervened, the district reopened the application to students throughout the district. However, priority is given to students within the feeder pattern.

“Everyone in the district pays for this expensive program, so everyone should have access to it,” Furrh says.

CLASS RANK INEQUITY

Lakewood neighbor Debra Bishop. Photo credit by Danny Fulgencio.

Lakewood neighbor Debra Bishop has advocated for a change in the class rank system for years—even before her daughter, Madison, dropped out of the IB program. As she saw an increasing number of students “cheat the system,” she and a small group of parents became more vocal about the class rank inequity.

“It really divides the school,” Bishop says. “You can’t say, ‘We’re all in this together’ because you’re not unless you provide the rest of the school with opportunities.”

When the IB program was implemented in 2010, it was intended to not only provide students with a holistic international education, but to bring families back to DISD schools. The plan worked—possibly too well. During the 2018-2019 school year, 600 students transferred to Woodrow, pushing the school beyond its capacity, according to records previously obtained by the Advocate.

The IB, AP, STEM and dual credit programs made Woodrow an attractive choice for students outside the feeder pattern—and outside the district—who wanted to graduate at the top of their class, Bishop says. Many opted into IB simply because it offered the most difficult program and, therefore, the highest weighted GPAs. Completion of the program practically ensured students would graduate in the top 10 percent of their class and gain fast-track admission to Texas colleges.

Competition for a spot in the top 10 percent is fierce. That’s because a state law requires all state-funded universities to automatically accept students who graduate in the top 10 percent of their class.

Texas created the policy in 1997 as an affirmative action rule to benefit students at predominantly poor and minority schools, like Woodrow. DISD data shows the majority of students at the school are minorities and students with low socioeconomic backgrounds.

But in 2019, Woodrow’s top 10 percent was comprised of 70 percent white students and only 23 percent economically disadvantaged students, according to DISD data.

Although some teachers say students will be discouraged from taking upper-level electives under the new system, Bishop hopes that students will have more freedom to choose classes that interest them.

“All the classes are equally hard,” she says. “IB parents would love to tell you their kids deserve more credit, but that is not always the case. You can’t tell me IB Film is harder than AP Calculus.”

Like IB, the AP program offers college-level coursework and has rolled out its own two-year diploma program for students who want to challenge themselves. AP Capstone consists of two complementary, yearlong classes students take during their junior and senior years. The program is multidisciplinary and culminates in a written thesis and defense designed to prepare students for college research.

Capstone is already at five DISD schools and will be available at Woodrow next school year.

“I’m hoping that what happens now is that kids pick a program they truly want to be in and go for it in any academy,” Bishop says. “That’s the way it’s supposed to be, not because you want to be at the top of your class.”

The strategy has worked well for her daughter. The senior excelled in her core classes and was free to take electives—some weighted, some not —that prepared her to major in business next year at the University of Colorado.

“Madison is going to college, but what about the kids whose parents can’t write the check?” Bishop asks. “We still have 50 percent of the school in general classes, and they need opportunities also.”

TAKING IT TO THE TEA

Woodrow parents opposed to the changes have pleaded their case with the Texas Education Agency and the Dallas ISD Board of Trustees without success.

A spokesman for the TEA says it does not provide any oversight on class rank. The decision on how to calculate rank is at the discretion of local districts. Although districts like Frisco and Plano let their school boards decide, DISD officials changed and approved the new system without consulting trustees, Marshall says.

There are three levels of education policy: state policy, board policy and regulation policy, which is set by the superintendent and his or her cabinet. Modifications to rank all happened at the regulation level, and the superintendent is not required to inform the school board of those changes, Marshall says.

Regulations can change multiple times a year, and they are very rarely anything that draws public attention, he says.

Superintendent Michael Hinojosa and his cabinet approved the regulation in August, and the school board saw a detailed version for the first time in about early September, after it had been passed.

“Ultimately, I’m not the decision maker,” Marshall says. “I sympathize with the argument that the change should not be retroactive, but all I can do is make sure they’re heard. I can’t make sure they get the outcome they want.”

Making no headway with the school board, parents filed an official complaint against the district. DISD spokeswoman Robyn Harris says she cannot comment on its current status.

If the complaint reaches Level 4 status, the final step in the complaint resolution process, parents can make one final appeal to the school board. The matter will be placed on the agenda of a future meeting. Trustees then have until the next regularly scheduled meeting to make a decision. If the board fails to reach a verdict, the district will uphold the decision at Level 3.

In the meantime, the class rank change remains in effect, immediately benefiting the majority of students, district officials say.

“When you talk about equity, everybody says, ‘Yes, I want equity, but not for me. Wait for them,’” says Oswaldo Alvarenga, assistant superintendent in teaching and learning at DISD. “If we see an inequity but don’t act, what are we really saying?”