The Greenville Avenue Christian Church burned down four months ago, but the fire hasn’t done anything to clear up the property’s fate.

If anything, its future is hazier than ever.

In fact, the entire imbroglio bears more than a passing resemblance to the bad old days in East Dallas, when developers and neighborhood residents fought each other with the political equivalents of tactical nuclear missiles.

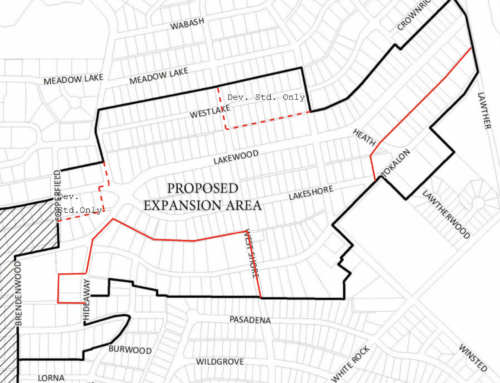

“What we’re trying to find is a development that is compatible with the neighborhood and that has the neighborhood’s support,” says Councilman Craig McDaniel, whose 14th district includes the site at the corner of Greenville and Llano.

“So far, we haven’t been able to do it.”

About the only thing anyone has done since the fire is dance around the property’s future as if they were trying to avoid getting caught in the flames. Here’s how ironic the situation has become: McDaniel is the only one who is willing to discuss the issue, hardly the sort of position that’s a favorite with most public officials.

The site’s developer, John Holmes, isn’t talking about his plans. The neighborhood, in the person of Lower Greenville Neighborhood Association president Karl Studins, points out that the site was zoned for single-family homes, and he says there is no reason why single-family homes can’t be built there.

An atmosphere of distrust hangs over the proceedings like a summer thunderstorm. The neighborhood, say the half dozen or so people I talked to, doesn’t trust Holmes, who it blames for the parking lot that sprouted up on the vacant lot shortly after the fire.

City inspectors quickly closed the lot in response to neighborhood complaints, but whatever confidence the neighborhood had in Holmes’ good faith was gone.

And Holmes, according to everyone I talked to, is less than happy with what he considers the neighborhood’s refusal to work with him to find a mutually beneficial use for the property.

At this rate, the vacant lot will remain a vacant lot well into the next millennium. And East Dallas already has entirely too many abandoned buildings, empty lots and the like.

On the other hand, this atmosphere of distrust hasn’t been supercharged by name calling and innuendos and counter-charges – one of the hallmarks of the bad old days.

Both sides went out of their way not to say anything nasty about their counterparts – and I gave them plenty of opportunities to do just that. Given how strongly each side seems to feel about the other, this may be a reason for optimism.

Each side seems to have left itself a little room to maneuver, another sign that this isn’t the bad old days. Holmes apparently realizes he can’t do anything without the neighborhood’s consent. The neighborhood seems to realize that Holmes is entitled to develop property he bought with the intention of developing. These attitudes are a beginning.

There is no reason to believe each side won’t eventually give a little, because it’s in their best long-term interests to do so. It’s hard to believe that anyone wants to bring back the bad old days, which were as unprofitable for the developers as they were for the neighborhoods.

It’s hard to believe that either side will forfeit an opportunity to further the progress East Dallas had made in the past 10 years in reviving itself. We’ve come entirely too far for that.