A fire that destroyed yet another neighborhood landmark in late December evidently will not extinguish a 12-year-old zoning dispute between the landmark’s owners and neighborhood residents.

Since the Greenville Avenue Christian Church at Llano and Greenville closed in the early 1980s, the investors who bought it repeatedly tried to rezone the 1929 Mission Revival and Romanesque building and adjoining property for commercial uses.

Each time, they failed in the face of overwhelming opposition from Greenville Avenue area homeowners who united against the expansion of commercial uses into their neighborhood.

And although a representative of the investors says there are no current plans to sell or rezone the now-vacant property, some members of the three closest neighborhood groups – Greenland Hills, Lower Greenville and Vickery Place – say they are not going to wait for the owners to make the first move.

“We’re planning to have a meeting to discuss the property, and then we’ll probably take a survey of the community to try to develop a consensus as to what would be an acceptable use,” says Bobbi Bilnoski of the Greenland Hills Neighborhood Association.

Most area residents would prefer that the six lots in question be used for housing or “a daytime use so that parking is available at night when the residents get home from work,” Bilnoski says.

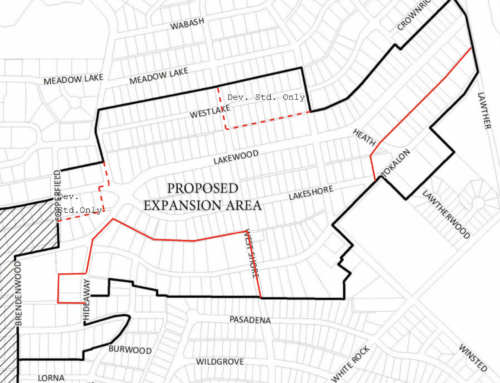

The six lots – consisting of the first four lots along Llano east of the intersection of Greenville and the fourth and fifth lots on Vickery Boulevard also east of Greenville – have residential zoning, which permits the operation of a church but not a business.

Bilnoski and members of the Vickery Place and Lower Greenville neighborhood associations says they feel most, if not all, of the lots would be viable for construction of single-family homes. They cite several new homes built in the immediate area in recent years as proof that in-fill housing in older neighborhoods is realistic.

Not so, says John Holmes.

“You couldn’t give away a lot at the corner of Greenville and Llano to a builder for constructing homes,” says Holmes, who describes himself as a representative of the owners but declines to identify the investors.

“We’ve always thought that restaurant zoning would be the best use for that property.”

Politically, at least, the Greenville Avenue Christian Church probably was doomed from the day the congregation decided to sell it. The building that no longer filled a need as a house of worship also happened to be located along one of the City’s most eclectic and congested entertainment corridors I the midst of an aging residential area that was being revitalized by active neighborhood groups.

While other old churches have been converted to restaurants, law offices and other uses, every use proposed for this church seemed to add to the problems homeowners were trying to solve.

Longtime City preservation activist Virginia McAlester says she saw the writing on the wall from the outset but could not dissuade her husband from joining the initial group that bought the church. The McAlesters no longer are associated with the investor group, she says.

“My husband attended that church as a child, and he wanted to save it with an adaptive re-use,” McAlester says.

“Before he bought a part of it, I told him, ‘Absolutely not,’ that an adaptive re-use would not work in this area…The neighborhoods felt assaulted in the 1980s, and they drew a line in the sand.”

Over the years, the investors and others floated several plans for the property, ranging from remodeling the church into a restaurant/bar (a zoning effort that was rejected in 1982) to demolishing the church and erecting several buildings designed for a mixed use of retail, offices and apartments (a zoning effort that was turned down in 1986).

During and after those attempts, uses discussed or proposed included: an antique mall, a museum for musical instruments, a showroom for a company that builds church organs, a landscaped parking area to serve businesses along Greenville Avenue, a police storefront and even another church.

Nothing panned out, sometimes because of concerns about neighborhood opposition, but also – especially in later years as the church building deteriorated – because the estimated cost of renovation or restoration was immense.

A recent repair estimate, provided last fall to a potential tenant who wanted to use the church as an antique mall, exceeded half-a-million dollars.

“I did a very cursory look at the building and applied some preservation criteria to it and estimated that it would require in excess of $600,000 to make the building useful for anything,” says Norman Alston, a Dallas architect and member of the City’s Landmark Commission.

“It needed thousands of dollars worth of work to repair or replace everything from walls to windows, heating, air-conditioning, plumbing, wiring, the roof, etc.”

After absorbing this devastating financial news, the prospective tenant dropped the idea.

The building had become, quite literally, a mere shell of its former grandeur. Even before the Dec. 22 fire, which is being investigated as arson by fire officials, the oft-vandalized church building was slated for demolition by the City because it had been classified as an urban nuisance, says Jim Anderson, a historic preservation planner for the City.

“The property owner had not done a good job of keeping it secure or repaired,” Anderson says. Demolition by the City was pretty much assured but could not be carried out until government-required documentation of the building’s architectural record – a process called mitigation – was completed, he says. The fire and ensuing emergency demolition short-circuited that process.

Once neighbors shook their heads and groused about living near a three-story building whose facade was punctuated by broken windows and doors pried open by vandals, and whose sanctuary had been defiled and stripped of usable materials by vagrants, drug dealers and graffiti artists.

Not they look at the freshly turned earth of a scraped lot and consider turf battles yet to be fought.

“I think everyone was sad to see the church go, but I don’t think there was a good solution” to the dilemma, says Karl Stundins, president of the Lower Greenville Neighborhood Association.

“And it’s still going to be a very difficult issue to resolve because there isn’t going to be a lot of gray area for the neighborhood.”

Church or no church, residents’ concerns today are much the same as those of a decade ago when it comes to land use and quality of life, says Gary Lawler, a board member of the Vickery Place Neighborhood Association.

“I hope there’s some middle ground we can find” among the interests of business owners, property investors and homeowners, he says.

“It’s one of those things where you can see everyone’s side…and exactly where they are coming from and why they ended up on a collision course,” McAlester says.

“It was just unfortunate for the building and for the people who bought into it thinking they were going to save it.”