For our March cover story about cinema-worthy East Dallas neighbors, we had the pleasure of photographing motorcyclist Leslie Porterfield.

In 2008, Porterfield set a Guinness World Record after her bike repeatedly shot across Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats at over 200mph. The Discovery Channel had turned its lens on her, as had BMW and TIME Magazine. Beyond her speed-demonry, Porterfield owns High Five Cycles, a local motorcycle shop; she’s also a bombshell and mother of twins. In short, she’s a badass.

And I had to shoot her.

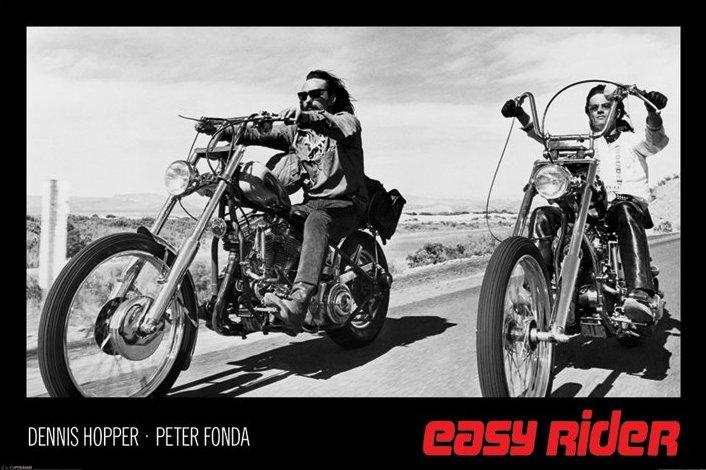

From the outset, two phrases kept coming to mind: Make it cool. Make it cinematic. After researching biker flicks, I settled on the 1969 Easy Rider movie poster that has graced many a dorm room wall. If your college days are still a little hazy, the poster looks like this:

Spoiler alert: Here’s what we ran on the cover:

But before we got to that point, many moving parts had to be threaded into place.

Where could we find a linear, barren backdrop near East Dallas? Would Porterfield be down with the concept? And what day and what time of day could we shoot? And where would the sun and shadows be at that time? What kind of cloud coverage could we expect? Could we light this shot from a moving vehicle? Could we get a driver? Whose car would we use? How high would that car sit? Could we get a photo assistant? What focal length would best communicate the shot? Shoot with a prime lens for sharpness or a zoom lens for flexibility? What would be the expectant flash recycle time if trying to burst toward the shot? Could we get a police escort? Could we do this quickly? Could we do this safely?

Questions like these start firing soon after an assignment comes down the pike and a concept kicks into high gear. Sure, serendipity plays into the equation, but photography seems to often be an explosive compromise between fantasy and reality. And sometimes things are wonderfully pleasant and you get what you want–or what you pleasantly didn’t expect; but sometimes, well, not so much. Pushing the needle in your favor can be a matter of isolating and accounting for variables. Preparation, they call it.

So, in a nutshell, things went down like this: Scour Google Maps, then Google Street Views–that bridge over Lake Ray Hubbard between Garland and Roulette looks perfect. Whose police jurisdiction is that anyway? Garland? Rowlett? Dallas? Call public information officers. Leave messages. The Dallas PIO never calls back.

Then drive to the prospective locale at the time of day you expect to shoot. Be sure to lash a tripod-mounted point-and-shoot camera to a passenger-side seatbelt at a correlative angle to the shot you want–push record, drive back and forth across that bridge. It’s a four-lane bridge. Where is the road roughest? Can you handhold your camera at 1/30th of a second to communicate an intense but controlled illusion of movement? If so, do you have enough neutral density filters to account for high noon light? Now review the footage. How much time do you have between rows of leafless trees and signs? Around 10 seconds? Good. Now recruit a driver. Photographer Jennifer Shertzer says she’s available. Now recruit a photo assistant. Photographer James Coreas says he’s available. Hope they show up on time. Hope you show up on time.

You did. Great. They did. Great.

And so, on a bright, chilly winter morning, we met at Porterfield’s shop and shot a few frames for inside the magazine. We used three SB-900 flash units, two motorcycles and an electric leaf blower. Here’s one of the shots we came up with:

And here’s a portrait we snagged:

Here’s a behind-the-scenes photo from James Coreas:

And then we flew over to Location #2: the bridge.

I drove. James drove. Jennifer drove. Strangely, Porterfield left her shop on a motorcycle well after we did yet she arrived shortly after we did.

Then it was a matter of choosing between shooting from a sedan or a crossover. The sedan sits lower, which is good, but the crossover has a wider wheelbase, meaning increased stability, meaning the potential for a slower shutter speed, meaning more intentional motion blur. Choose the crossover.

Then we were off.

And, naturally, the first angle doesn’t work. Porterfield’s too backlit. Then there’s another issue: James yells, “The flash is blowing away!” Which it was, because it was hanging out of a car window on a boom and sitting in a small octabox that acted like a sealed parachute when driving at 35mph. Despite the layers of electric and duct tape holding the rig together, things were getting sketchy. Which is to say nothing of the road.

And so we ran without flash on the second go-around. But the angle was wrong. Too high. So, somewhat on a whim, I lied on the rear floorboard of the vehicle with my shoulder holding the rear passenger’s-side door open and my head angled down near the ground.

“You’re crazy,” Shertzer said.

Still, we crossed the bridge at 35mph while I shot at 31mm and Leslie dug into the pedals.

Turns out that 1/30th was much too slow, and 1/250th was sharp enough for Leslie but slow enough for the desired amount of motion blur.

After a few passes across the bridge, we called it quits, partly because I felt we’d gotten the shot, and partly because I felt another pass might test our luck.

Later, after a simple bout of color correction, exposure adjustments, split-toning, cropping, vignetting, gradient layering, dodging, burning, sharpening and formatting, the shot was done. In the end, despite the hours of pre- and post-production, the photo we ran was made in only 0.004 seconds.

And here’s the cover: