NOTHING POLARIZES AN ASSEMBLY OF CITIZENS and civic leaders like a discussion about affordable housing. So when the Dallas City Council, determined to tackle a metro-wide shortage of accessible homes, met last year to consider the construction of multiple Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) developments near our neighborhood, drama ensued.

A proposed project along Central Expressway enjoyed the support of most Council members and several housing advocates who said it would provide 200 homes, half of them at an affordable rate, in a “high-opportunity area.”

But a number of neighbors and their Council representative, Adam McGough, opposed the project. Dissenters cited homeless camps, drug deals and public nudity happening in the area.

City Council representative Adam Bazaldua said he couldn’t believe what he was hearing. He admonished those who conflated people earning less than the median salary with criminals. The objections, he said, were “frankly about race.”

Following the combative session, the Council voted 9-6 to approve the project. But the neighbors took the fight to State Rep. John Turner, who had the right to override the City’s decision, and the apartments were never built.

The case drew criticism from local media and City leaders, who are under pressure to build homes and reduce what researchers at Up For Growth say, as of 2020, is an 87,000-unit deficit.

As house prices and rents increase and conversations about housing become more fraught, one might wonder who is right — homeowners demanding a say in neighborhood planning or those who argue we need to build more housing at every opportunity?

The answer, of course, is both. And neither.

Policymakers cannot ignore the neighborhoods’ desires and concerns. They would be out of a job if they did.

But pressure to construct and rehabilitate more homes is only going to increase, and negative public opinion about affordable housing can be a big barrier to meeting Dallas’ mounting need.

If we cannot strike up more constructive conversations, promising developments will keep croaking in infancy, and our city’s housing demands will go unmet, say those inside the city planning world.

Unaffordability can lead to housing insecurity, homelessness and a host of societal problems that affect every socio-economic bracket, says David Noguera, director of the Dallas Department of Housing and Revitalization.

Ensuring our city is a place where people of varying incomes can rent, finance or purchase a home begins with public support for all types of housing, he says.

“We can help create and preserve affordable places for people making around $50,000 a year — bear in mind this means some teachers, your delivery drivers, post office personnel — or we can let them figure it out themselves,” he says.

The problem with the latter, he says, is sprawl and the loss of valuable members of society, as residents move farther out or leave Dallas for somewhere more affordable.

“Dallas is going through a level of growth we have not seen in years,” Noguera says. “We are not building enough housing fast enough. Take the word affordability out of it altogether — we need more, period.”

Research from Up for Growth, in a report titled Housing Underproduction in the U.S. 2022, backed that up.

“Spotting and responding to under-production trends can improve lives, economies and the planet,” said Mike Kingsella, CEO of Up for Growth, a non-profit committed to solving the housing shortage and affordability crisis.

He attributed underproduction in more than 200 metropolitan areas to “NIMBY-ism (not in my backyard) and exclusionary zoning.”

Noguera has seen examples of people who say they support affordable housing but don’t want it in their neighborhood.

That’s often due to misunderstanding what affordable housing is, he says.

“When people hear ‘affordable housing,’ they think it is going to attract undesirable neighbors,” Noguera says. “I think, from one perspective, we need to educate our residents on what it means and on the impact of our decisions.”

But in some cases purported concerns about traffic, parking, building height, property values, the environment or character of the neighborhood mask biases and racist attitudes, he says.

“I have heard things at these meetings that make my jaw drop,” he says. “Those kinds of comments make it difficult for everyone involved in trying to get something done.”

A HOT-BUTTON TYPE OF HOUSING

The housing tax credit is the City’s most essential financial tool for producing affordable housing. It’s not the only one, but it is a good place to start as we learn about what affordable housing is and is not.

It is a term we will hear more as the Dallas area strives to build enough homes to accommodate a population that, according to the Dallas Federal Reserve, grew by almost 100,000 in 2020-21.

The housing tax credit has been around since 1986. (Texas removed the words “low-income” in 2005.)

Through this program, banks and other corporations put cash into a development that includes affordable units in return for 10 years of credits against their taxes.

“The term is a very loaded one, and it attracts attention from all sides of the housing debate,” Noguera says.

People often conflate housing tax credit projects with slums, poverty and crime, but in reality, the developments he’s looking at all involve mixed-income housing, he says.

AFFORDABLE HOUSING, A GLOSSARY OF TERMS

LIHTC/HTC: Low Income Housing Tax Credit or, in Texas, Housing Tax Credit, is the City’s most essential financial tool for producing affordable housing. Written in 1986, the program allows banks and other corporations to put cash up front into a development that includes affordable units in return for 10 years of credits against their taxes.

SECTION 8: Named for Section 8 of the United States Housing Act of 1937, this housing choice voucher program is the federal government’s major program for assisting very low-income families, the elderly and the disabled to afford decent and safe housing in the private market.

WORKFORCE HOUSING: Urban Land Institute defines workforce housing as housing affordable to households earning between 60% and 120% of area median income. That’s about $36,000-$72,000 a year in Dallas. The term aims to conjure images of young teachers, mail carriers and health care workers.

ACCESSIBLE HOUSING: As housing proponents try to scrub affordable housing’s image, they try other words that mean essentially the same thing, and this is one of them.

MISSING MIDDLE: Architecturally, between apartments and single-family houses, are lower-density multi-unit or clustered housing types, such as duplexes, that are closer in scale to houses. The term also is often used to describe the population who would live in these dwellings.

NIMBY: Not in My Backyard. Coined in the 1970s, according to Oxford Languages, it is a person who objects to the sitting of something perceived as unpleasant or hazardous in the area where they live, especially while raising no such objections to similar developments elsewhere.

YIMBY: Yes in My Backyard. Pushing back against the NIMBYs, these supply side advocates are pro-development activists in pursuit of equity, or they’re gentrifying tricksters, depending who you ask.

GENTRIFICATION: When an influx of more affluent residents and businesses change the neighborhood’s character.

EXCLUSIONARY ZONING: These ordinances place restrictions on the types of homes that can be built in a particular neighborhood with the intent of restricting housing for low-income residents. Common examples can include minimum lot size requirements, minimum square footage requirements, prohibitions on multifamily homes and limits on the heights of buildings.

SUPPORTIVE HOUSING: Temporary, long-term or permanent, supportive housing combines affordable housing with intensive coordinated services, or wraparound services, such as medical or mental health care.

NOAH: Naturally occurring affordable housing is available on the regular market, open to anyone and not subsidized by a government or nonprofit, but it falls within the budget of many families.

MARKET-RATE HOUSING: Housing that is available on the private market, not subsidized or limited to any specific income level.

DPFC: Created in 2020, the Dallas Public Facility Corporation is a public nonprofit that partners with private developers to build affordable housing. It has been used successfully in other municipalities, and Dallas staffers say they are learning best practices by watching for problems and successes in other metros.

DHA HOUSING SOLUTIONS: Formed in the 1930s as the Dallas Housing Authority, the agency oversees voucher programs and other programs to find homes for low-income residents.

WALKER ET AL. VS. HUD: In 1985 Dallas resident Debra Walker and six other women sued HUD, the City of Dallas and Dallas Housing Authority over segregated and inferior housing and won, forcing the DHA to change its practices and spread affordable housing throughout the county. It’s one reason many City leaders are pressed to develop affordable housing outside of South Dallas.

A good project might include a third of its units at market rate, a third at 30% area median income and a third at 60% median income, for instance.

The City scores housing tax credit projects based on various components — crime rates in the surrounding census tract, for example, or proximity to transit and medical hubs.

When a housing project contains “affordable” or “tax credit” in its description, that does not mean voucher housing, transitional housing or a homeless shelter, Noguera says.

Those are things we as a community also have to address, he says, but when people conflate those things, it does nothing to advance the creation of more homes for Dallas residents.

DAMAGING DIALOGUE

HTC projects are not the only ones to rile up the neighbors.

Developers of a proposed mixed-use project in East Dallas, Standard Shoreline which would include 50% “attainable” housing, have held meetings with neighboring residents in hopes of explaining themselves.

“Attainable” units at this development, which would occupy the former Shoreline City Church site on Garland Road near Centerville Road, would be for people making about 80% of the area median income, Daniel Smith, a managing director at Ojala Holdings says, which would mean housing for educators, health care workers and mail carriers, for example.

But Ojala’s neighborhood meetings have been intense.

Dallas Morning News columnist Sharon Grigsby wrote, following an April session to discuss the project, that it was “the ugliest town hall (she) had ever attended.” Citizens reportedly trashed hypothetical Shoreline residents — a bunch of “drug addicts and prostitutes” — bashed the church that owns the property and harassed City Council representative Paula Blackmon.

The president of Lochwood Neighborhood Association, Scott Robson, when introducing the developers at that meeting, said, “they will be doing their dog and pony show about their concerns for teachers, nurses and firefighters.”

Grigsby concluded there were valid concerns about the project buried beneath the hateful rhetoric, but that the way it was delivered was “hardly the way to do what’s best for your neighborhood.”

The Shoreline forums have been emblematic of what happens when we do not have constructive ways to discuss housing.

That 2021 Council meeting where members debated an HTC project at Central Expressway and Forest Lane was similar — neighbors opposed a 50% affordable housing complex due to its proximity to a “homeless camp,” they testified about drug deals and public nudity near the site, complained that developers of lower income apartments would let just anyone live there and said the area already had enough diversity.

Councilman Bazaldua said he “heard a bunch of NIMBYs who were not only saying to people — people like cooks and front-line, essential workers, people who make around $30,000 a year — that we do not want them, and then going even further and comparing the working class to criminals.”

Councilman McGough, who has seen his share of these types of meetings in his district, says that when people associate affordability with crime and vagrancy, it gives ammunition to critics who would call all concerned neighbors NIMBY or worse.

“There are going to be outliers and people who say things that they’ll interpret as racist and other things,” he says. “And it absolutely kills me when it happens, because the majority of people, in my experience, genuinely want to help figure this out.”

So, how do we get to a place of less anger, more understanding and collaboration to more smoothly bring housing to all Dallas neighborhoods?

EDUCATION —WHERE WE STAND

We need all types of housing — from expensive houses on large lots to townhomes and condos to multifamily buildings.

The City also has Community Development Block Grants to build single-family homes, a repair program to preserve single-family homes and a downpayment assistance program, says Kyle Hines, assistant director of Dallas Housing & Neighborhood Revitalization.

Homeownership remains the primary driver of household wealth.

But when people give up on homeownership, because of high prices or too much competition, they enter the rental market, explains West. Then there is less supply and more demand in the rental market. “People who could pay more and cannot find a place go down to the next level and it can trickle down until the people in the lowest AMI category are out of luck.”

Noguera says it is critically important that whatever the city is investing in serves a mixture of incomes. “I don’t want the conversations to be pigeonholed into discussing housing for a particular group of people, because our city needs more housing at all price points,” he says.

An “affordable dwelling” is often defined as costing 30% of a person’s gross income, whether you are at the lower or upper-midpoint of the income spectrum.

“At all levels, if you’re spending more than a third of your income on housing, it impacts your ability to pay for the basic things like food, gas, car insurance and health care.”

Affordable housing is not just for poor people, he says. However, those with lower incomes have a tougher time obtaining housing, which is why affordability for lower-earning house-holds receives more attention.

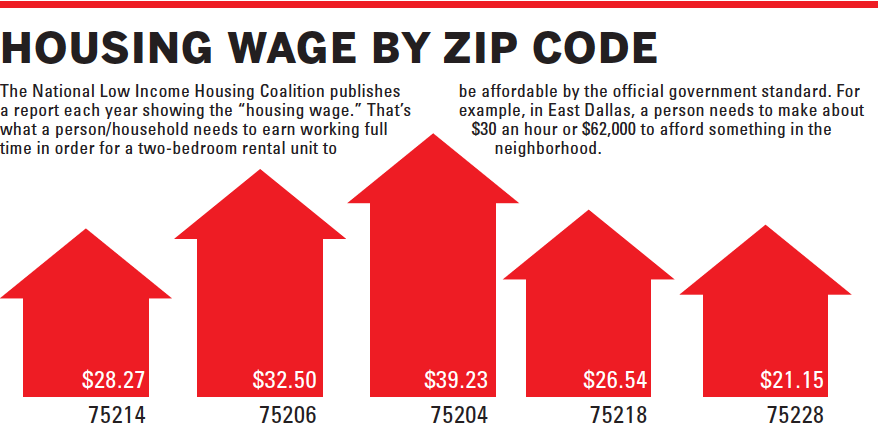

The median annual income for Dallas households is about $62,000, he says, while the typical for-sale home is about $340,000 and the rent is approximately $2,500 a month.

“That is the issue. Those gaps,” Noguera says.

KEEPING NEIGHBORS IN THE LOOP

KEEPING NEIGHBORS IN THE LOOP

The Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs has a running list of housing tax credit projects across the state and their status.

But homeowners in the vicinity of any proposed project should be hearing about these things before they even land on a list like this.

While council members don’t agree on everything, many have said the only hope of gaining neighborhood support for most multifamily projects, much less affordable ones, is to bring neighborhood stakeholders in on plans from the start.

Councilman Chad West, who is on the City’s housing committee, points to the way Councilwoman Cara Mendelsohn introduced a homeless shelter to her district. After the Council agreed to place one in each of 14 districts, she went to her constituents right away, explained the situation and got their input, effectively letting them decide where it would go.

“I wish I would have done that,” West says, and it demonstrates a way we might gain neighborhood support and improve the public perception of affordable housing developers.

In his 16 years working for Dallas, McGough says he’s learned one thing for sure.

“The No. 1 thing you do, is you communicate with the neighborhood, identify changeable pieces, and you do your best to honor the community.”

The developer is responsible for “effectively communicating” with the people, he says, and while some City officials have said the same, others said it is also a responsibility of the Council member.

FIXING WHAT WE HAVE ALREADY

Another barrier to public support in dense areas is the condition of existing multifamily communities.

In December, the Dallas Police Department began pinpointing “hotspots” that record the most violence in the city. A stretch of Ferguson Road in East Dallas, where there are multiple aging apartment buildings, was near the top of the list.

In each violent-crime category, micro-level data show the glut of Dallas’ violent crime happening in rundown multifamily residential communities.

At a recent safety committee session Dallas police Maj. Paul Junger said, “apartment complexes are driving our murders.” So, it is easy to understand why nearby residents are not clamoring for more.

ALL HOUSING CONSIDERED

The stories we tell about the “affordable housing crisis” often “fail to explain why housing is increasingly out of reach for many people or the societal benefits of creating and preserving affordable housing,” writes housing researcher Tiffany Manuel, in the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Many see differences in housing quality as an inherent feature of the market, as inevitable, Manuel says. They believe differences in affordability and access indicate that the market is healthy.

“Those notions allow us to rationalize disparity,” she says. “This idea allows us to justify the fact that so many live in unstable situations.”

Once people understand structural causes of inequity — such historical redlining, segregation and unfair housing practices — they might better accept the need for structural solutions.

“If we do not explain the systemic causes and consequences of lack of affordable housing, we allow the view that the housing market is beyond human control to go unchecked,” Manuel says.

The more we learn, the more enlightened our discussions about homes and the health of our housing ecosystem, the better and stronger our city can be, says Councilman West, who is working on a “more visionary” housing document to complement the City’s Comprehensive Housing Policy.

Just as closed-minded homeowners who oppose everything are problematic, hurling insults at them can be just as harmful, because it impedes much-needed communication and understanding, McGough says.

Three years of research by Stanford on strengthening the affordable housing sector’s public image reflects the limitations — yet the significant role — of language.

“Changing how we talk about affordable housing for all will not, in itself, rewrite the future,” Manuel says. “But it is an important part of reaching that dream.”