Forget the latest culinary craze — here’s what keep the regulars coming back, and back, and back

It’s a challenge to keep up with the trendy and innovative restaurant landscape in Dallas. Every day, it seems, brings the announcement of a new upscale taco joint or slow-food gastropub or microbrewery.

Amid the blur of media clamoring to cover the city’s latest and greatest foodie hotspots, it’s easy to forget the neighborhood restaurants that have stuck with us over the long haul.

But the regulars don’t forget.

They patronize their favorites week in and week out, sometimes daily. Their allegiance isn’t just about the food. They tend to be loyalists and creatures of habit, in contrast to those of us who have restaurant attention deficit disorder.

The neighborhood eateries with established regulars aren’t typically the ones enjoying Twitter and blogger buzz. If we lost them, however, they would leave gaping holes in the fabric of our community.

While most of us play the restaurant field, we salute the regulars who make sure our neighborhood’s dining staples will be around when we crave them.

The guy who knows everyone (and everyone knows him)

The bar is Joe Porter’s favorite place to dine, here at Terilli’s and elsewhere, too, because it’s the best place to strike up conversation. Photo by Danny Fulgencio

“They call him the mayor of Greenville,” whispers a waiter at Terilli’s, beckoning toward Joe Porter.

Porter had grabbed a small booth near the bar and was sipping iced tea, since it was still early in the afternoon. (“The sun has to be over the yardarm before I’ll take a drink,” he later explains, quoting the old sailor expression. “I was just raised that way.”)

He’s frequented the restaurant “since Jeannie [Terilli] opened the place” more than 25 years ago, and remembers when her daughter, Amanda, would run downstairs and grab her coat on the way to elementary school. The little girl often gave the Irishman a warm “hello.”

“And when I got older, she never forgot me,” Porter says of Amanda Terilli Ahern, who is now a managing partner. Ahern greets the family’s longtime customer with a hug on this particular day.

The Terilli’s folks call him the mayor of Greenville because their bar is only one of Porter’s haunts.

“Why not be a conservationist?” Porter asks. “Park your car to where you can walk to four or five different bars.”

This is his routine two or three times a week, most often around Lower Greenville, Henderson Avenue or Uptown. Porter lives in Casa Linda and works in the area, so these hotspots are conveniently located when he wraps up business for the day.

“Hey, it’s around-town Joe!” says Blue Goose Cantina manager Jim Jernigan when Porter stops in across the street from Terilli’s.

“Around-town Joe” is another of Porter’s monikers, this one given by Candleroom nightclub owner Tommy DeAlono, Porter says. He’s also been nicknamed Crocodile Dundee “because I do my walkabout,” he says. Others know him simply as Mr. P.

It seems that everyone knows Porter, and vice versa. He was a regular at The Londoner when it was on Lowest Greenville, before Barry Tate decided to move it to Uptown. “Whenever a space came available, [Tate] said, ‘I’m going to open up,’ ” Porter says. He knew Peter Kinney as The Dubliner’s bartender, before Kinney and Feargal McKinney took over the place and later opened the Old Monk, Idle Rich Pub, Blackfriar Pub and Capitol Pub.

Porter recently spotted Pat Snuffer in the parking lot of the Greenville restaurant and stopped to chat, learning the longtime burger joint would be torn down and rebuilt. He spent time with the late Matt Martinez — “the recipe guy, the front guy, the schmoozer,” he says — while his wife, Estella, ran the business. When Martinez died, Porter says, “Estella never missed a beat.” He also knew the late Bob Peterson, who opened Blue Goose and Aw Shucks (“Everyone called him ‘Dirty Bob,’ ” Porter says. “I just called him ‘Bob.’ ”), and he knows the Blue Goose’s Jernigan as “Elvis,” a nickname from his sideburn days.

“Anytime you hear anybody call him ‘Elvis,’ that’s one of the old crew,” Porter says.

Porter will give any place a try, but the places he visits time and again have a couple of distinct qualities.

Good food is the initial draw, he says, but “I’m not talking about 3-star Michelin. If I like the chicken-fried steak, I like it. If I don’t, I don’t.” Even if the food is “just OK,” Porter still might sit at the bar, sip a Guinness and talk to people.

“I like to walk in somewhere like ‘Cheers,’ where you know people, they know you. That’s my kind of place,” Porter says. “The stuffy corporate thing, I don’t like.”

He knows when a certain person will be at happy hour at this bar, and someone else will be grabbing a bite at that restaurant, and he moves from place to place accordingly. He knows the bartenders pretty much everywhere.

“Bartenders were the original psychiatrists. The layman’s psychiatrist,” Porter says. “I love hearing the stories.”

He has plenty of old friends, but loves making new ones. “I’m an Irishman,” he says, explaining his ability to strike up a conversation with anyone in his vicinity.

And sometimes, Porter just listens.

“I’ve been in marketing and sales one way or the other for 40 years, and when you are, you become a people watcher — they are the ones who are going to buy your product or not,” Porter says. “What better place to watch people than in bars and restaurants? Because you see them all the way from the business side to the wild side.”

The 68-year-old makes a point to listen to people much younger than him. He has done this for decades, since the heyday of the Gypsy Tea Room and Trees in Deep Ellum. Porter used to make the rounds there, too. Once he was asked by a young guy checking IDs, “Are you lost?”

“It kind of looks like it, doesn’t it?” Porter responded, laughing.

The “old guys” with whom Porter converses wonder why he wastes his time.

“Our generation runs the world right this minute, but in a very short period of time, our generation is not going to run it — theirs is,” Porter says. “So I want to know how they think. I don’t want to be sitting on the couch and saying, ‘I don’t know what the hell is going on with the world.’

“Why would they want to talk to me? I don’t know. But a lot of them do, so I talk to them.”

Over the decades, he has watched as restaurants and bars in Dallas have opened and closed, expanded or moved. He believes he knows the secret to the enduring success of places like Terilli’s and the Blue Goose.

And it’s not the food.

Sure, the food should be good, Porter says. “But say the food is good, you know what the rest of it is? People.

“You can have the right idea, but if you don’t have the right people to put it into effect, it’s not going to work.”

Terilli’s

2815 Greenville

214.827.3993

The Blue Goose Cantina

2905 Greenville

214.823.8339

Order like a regular:

“Food is simply a matter of personal taste,” Porter says. But in his opinion, these are the best menu items at Terilli’s and Blue Goose:

Terilli’s: “Tom Landry used to eat here, and there’s a dish called the Tom Landry. It’s very good,” Porter says of the grilled chicken breast with roasted red peppers, Texas goat cheese and ancho chili pepper sauce. He also likes the restaurant’s soups — lobster bisque, cream of jalapeño and minestrone.

Blue Goose Cantina: Porter likes to order the salsa verde enchiladas with extra verde sauce, and charro beans instead of refried. “I believe the Blue Goose has the best verde sauce in town,” Porter says. “I’m trying to get them to tell me [the recipe], but they won’t say.” His other go-to is the beef chile relleno. “It’s made Durango-style because the people who created the dish are from Durango,” he says.

The neighborhood loyalists

For the last year and a half, Peter and Judy Czarny have spent every Friday night at Daddy Jack’s on Lower Greenville.

It’s their date night, and they have a standing reservation for a booth. The New England chowder house with red-checkered tablecloths and a menu devoted to fresh seafood is cozy and tranquil.

“It’s kind of a bit away from the maddening crowd, so to speak, so it’s more comfortable,” Judy Czarny says. “If you go farther up toward where the old Whole Foods used to be, that gets into the rush and bustle, and it’s kind of nice when you go out on Friday to not have to worry about that.”

They discovered the place nearly a decade ago when their now 26-year-old son, Nathan, was a high school senior. The Czarnys don’t eat red meat, so Daddy Jack’s was a perfect find for them, and “we’ve been going ever since,” Judy Czarny says.

“We’ve tried other seafood places around Dallas, and for the price and the quality, you can’t beat Daddy Jack’s,” she says.

Also, Czarny says, “we like to stay in the neighborhood,” and Daddy Jack’s is a true neighborhood restaurant. Owner Cary Ray is “100 percent local. They live in the neighborhood, and they have their business in the neighborhood, and that’s a big plus, in my opinion,” she says.

The Czarnys are on the Wilshire Heights neighborhood board, and Ray donates gift certificates for its annual chili cook-off prizes or silent auction. “He’s always really good to our neighborhood,” Czarny says.

Ray is there every Friday night when the Czarnys dine. Part of the experience is chatting with him and also with Felissa, one of the waitresses, who takes care of feral cats. “We enjoy talking to her about how all that’s going,” Czarny says.

“Of course, when everybody knows you, it’s nice going there,” she adds.

Daddy Jack’s

1916 Greenville

214.826.4910

Order like a regular

The Czarnys generally order one of the specials, such as “sea bass, ahi tuna, halibut — a variety of things like that with a variety of different sauces,” Judy Czarny says. Owner Cary Ray offers only what he can procure fresh, so between the specials and the regular menu (“We’ve probably had everything on it,” she says), they can’t go wrong.

The routine customer

Victor Nichols Jr. used to take his mother to the beauty shop at Buckner and Northcliff. Because Alfonso’s was in the same shopping center, “it was real convenient to take her to the beauty shop then eat with her at Alfonso’s,” Nichols says.

He started dining there 18 years ago, and his mother has since passed away, “but I continue the same schedule,” Nichols says. He’s still at Alfonso’s every Thursday afternoon.

He also eats there on Sundays after attending church Downtown at First United Methodist. Sometimes his sister, who also attends church there, joins him.

“I always have the same waitress,” Nichols says. “Her name is Cynthia, and she’s been there about five years, so of course when I go in twice a week, she knows exactly what I want.”

Nichols is a 66-year-old retired bachelor who worked for the City of Dallas water utilities for 32 years. He eats out nearly every day and has a pretty set routine — the Casa Linda El Fenix for the Wednesday enchilada special, Circle Grill at I-30 and Buckner two or three times a week for breakfast, and the Black-Eyed Pea at Town East at least once a week.

“I just figured, you know, being by myself, it’s just easier to go out and eat,” Nichols says.

Just like at Alfonso’s, he sits in the same sections and is served by the same wait staff each time he dines. He learns about their lives — Cynthia has two children, he says, and the husband of his Black-Eyed Pea waitress is a printer at the Dallas Morning News.

The waiters know Nichols, too, and take care of him.

“My waiter at El Fenix, Francisco, is really, really good,” Nichols says. “He’ll do special things for me — give me extra tortillas and chips and let me take them home.”

Cynthia, who prepares a glass of iced tea as soon as Nichols walks into Alfonso’s, gives him similar special treatment.

“She usually gives me garlic rolls to take home,” he says, “and today she put an Italian cream cake in there, so you can’t beat that.”

Alfonso’s Italian Restaurant

718 N Buckner

214.327.7777

Order like a regular

Nichols is a vegetarian, and he appreciates the good vegetables and fresh salads on Alfonso’s menu. On Sundays, he always asks for his regular — vegetable pizza. “It’s kind of strange to have a vegetable pizza, but it works out real good,” Nichols says. “Cynthia will make me a real big salad, and I can take some of the pizza home.” On Thursdays, he changes it up, usually ordering something like the veggie baked lasagna or the minestrone soup.

The retired old men eating out

Ed Waters, Morris Holman, Ross Williams and Boyd Jones contribute to the lively conversation each weekday morning at Barbec’s. Photo by Danny Fulgencio

Head to Barbec’s any weekday morning between 7 and 8:30 a.m., and you’ll find the Romeo Club sitting in the corner of the main dining room.

Any weekday but Thursday, that is.

“It used to be five days a week, but one of our group began laying out on us because he had to play golf on Thursday,” Dick Atkinson says.

“I got a prescription from my doctor to play golf,” Ed Waters quips, and the other men shake their heads and laugh.

Romeo stands for “retired old men eating out,” they explain. They meet at Barbec’s because most of them live near White Rock Lake, so the diner is conveniently located.

No one can remember when this morning ritual began.

“We’ve been here so long, we’ve told all the jokes we know,” Atkinson says. “We just say, ‘No. 2,’ and everyone laughs.”

It’s been long enough that the restaurant puts out a “reserved” sign for the men each morning, and their waitress, Carrie Skaggs, knows their usual orders.

“And just like being in church, everyone sits in the same ol’ pew,” Jim K. Brown says.

Brown retired from the United Methodist Church; he pastored both Ridgewood Park and Lake Highlands Methodist churches during his years in ministry.

“And boy, when he retired, he retired. He comes back on Easter and Christmas,” Waters says, ribbing Brown.

“I’d have to say he makes it about 50 percent of the time,” Atkinson says.

“I couldn’t do it 100 percent,” Brown admits. “I never had perfect attendance.”

Atkinson also retired from the United Methodist Church, but still works for White Rock United Methodist overseeing pastoral care and visitations.

Most of the men know each other because they attend the same Sunday school class at the church, located a few blocks from Barbec’s in Little Forest Hills. The exception is Jerry Cole, a Main Street Church of Christ member and also the quietest of the bunch.

Cole used to sit at a table behind the one where he sits now, and after a while, the men encouraged him to move closer and join them.

“Jerry kind of keeps us in line,” Waters says.

“It’s not an easy job,” Cole says.

Boyd Jones joins the bunch around 8 a.m. He’s part of their Sunday school class, too. Another occasional member is their Sunday school teacher, Morris Coleman, a recently retired Eastfield College professor.

“He’s become unreliable now that he’s retired, but he is an honorable mention,” Waters says.

“The other folks who come in here have the benefit of overhearing,” Atkinson says, gesturing toward the customers seated elsewhere in the dining room.

“Yes we do!” a woman pipes up.

“We’re often called the think tank of East Dallas,” Waters says.

“But we don’t think much,” Brown says.

“And we don’t think often, either,” Waters says.

When the jokes cease, if they ever do, the discussion revolves around that day’s Dallas Morning News headlines.

“This group is never serious about anything except politics and religion,” Brown says.

“Well, we start the day with a laugh,” Waters says.

“And it goes downhill from there,” Brown says.

Barbec’s

8949 Garland Road

214.321.5597

Order like a regular

“Coffee is all I have,” Atkinson says. “I still have a wife who fixes breakfast for me.” Jones orders “two pancakes and a strip of bacon — I don’t want to overdo a good thing.” Cole’s usual is oatmeal with raisins. “We’re creatures of habit,” Waters says. “Except me — I change every day.”

The fortuitous friends

Stelly Hofelt remembers exactly when she began eating breakfast at Goldrush Café. It was in 1991, when her husband, Jerry, broke his leg.

Up until then, he would get up every morning and fix his own breakfast before going to work, she says. When he couldn’t, she began cooking for him; after a week of it, she suggested they go out to breakfast on Saturday.

She didn’t realize what she was signing up for.

“Once he retired, my comment was, ‘We are not going to go to the Goldrush every day,’” Hofelt says. “By God if we aren’t here every day.”

They aren’t the only ones. Each morning the main dining room fills up with customers who know each other so well, they talk across the tables and swap seats on occasion.

The room isn’t large, and it was the only dining area before the restaurant expanded into the adjacent space next door, “so when you came for breakfast, you sat with whoever happened to be here,” Hofelt says.

“When this gentleman started coming, he started pushing tables together,” Hofelt says with a gesture toward Ted De Bosier.

De Bosier has traveled extensively, and everywhere he goes, he seeks out a place “that when you walk in, it feels distinct,” he says. When he moved to our neighborhood and discovered the Goldrush, he knew he had found what he was looking for.

“My analogy is, everyone looks for a ‘Cheers’ bar, and this is it in a breakfast place,” De Bosier says. “People don’t know each other, and in half an hour, they’re good friends. It really is fodder for good conversation and camaraderie, and even though there are disagreements about religion and politics, it’s about the friendship.”

“And I don’t sit with people who disagree with me,” Hofelt quips.

The friendships would be unlikely outside the incubator of the Goldrush, they say, but because they are breakfast companions, they now attend each other’s Christmas parties and know each other’s relatives.

In fact, “it’s like my family,” Hofelt says.

And owner George Sanchez is the patriarch.

“This would not be the place it is if it wasn’t for George,” De Bosier says.

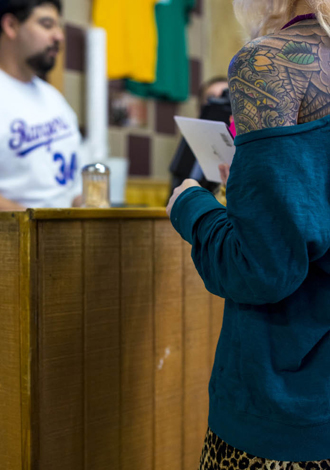

They laud him for embracing the motley crew that makes up his clientele, including the patrons with “purple hair and tattoos,” Hofelt says.

“It’s the old people in the morning and the rock crowd at lunch, and George gets along with all of them,” De Bosier says.

Once you order something two or three times, Sanchez will remember it as your regular, they say. They’ve joked with him that he should put “The Regular” on the menu, and list the cost as “market price.”

“You don’t even have to use the menu,” points out Rich Grayson, who’d grabbed a seat next to Hofelt. Even still, Sanchez can keep track of everyone’s preferences and nuances, they say.

Hofelt remembers coming in on one of Sanchez’s days off and complaining about the bad service. Another regular corrected her: “We don’t get bad service when George isn’t here; George spoils us.”

“And I thought, ‘That’s true,’ ” Hofelt says. He then adds, “It’s not that I want to critique the food, but we don’t come here for the food.”

The reasonable cost of meals is a draw, however.

“If you’re going to be a regular, you’re not going to pay $15 for breakfast,” Grayson says.

Sanchez modestly credits his customers for making his restaurant what it is. He’s going on 33 years in business, and says 85 to 90 percent of the clientele are regulars. He has watched customers who were dating marry and have children, and “now their kids come in and have a usual,” he says.

“If it wasn’t for them, there wouldn’t be a Goldrush,” he says. “They love it here, and I love serving them.”

The conversation around the tables continues well into the morning. Hofelt passes around the creamer pitcher as she sees a need arise, and De Bosier buses dishes as people finish their food. Coffee cups clink in affirmation of a statement or idea. And laughter is prevalent.

“Sometimes there’s so much laughter here in there morning, I wonder if people think that we’re drinking,” Hofelt says.

Gold Rush Café

1913 Skillman

214.823.6923

Order like a regular

Grayson usually orders oatmeal or a breakfast taco. One of Hofelt’s classic go-to meals is two poached eggs, sliced tomato and avocado, and a toasted English muffin, which she turns into a breakfast sandwich. Most mornings, De Bosier orders two poached eggs, a toasted English muffin, grits and either sausage patties or sausage links. “I’m pretty boring and simple with my palate,” he says. Sometimes, though, he splurges. “Their real strength is in their Mexican-style dishes — huevos rancheros, and their breakfast tacos and morning burritos.”