Four years ago, when a federal judge forced Dallas to establish single-member City Council districts, the pundits and wise guys predicted the end of effective government.

They were wrong then, and they’re still wrong.

Nothing demonstrates this more than the series of neighborhood-City meetings held in January and again this month to discuss a number of knotty traffic problems in the M Streets and Vickery Park areas relating to the Central Expressway construction.

This is remarkable for any number of reasons, not the least of which is that the City staff’s traditional attitude toward traffic and road disputes in East Dallas has been to bulldoze first and ask questions later. Who could forget their wonderfully wacky plan to add a reversible lane to Greenville Avenue?

But this “we know best and you only live there” posturing – last seen when we had the reversible lanes on Ross and Live Oak shoved down our throats – is a refreshingly absent from the current discussion.

Instead, staffers and neighborhood residents are meeting to work out a reasonable solution to what in the past might have produced TV news shots of people hollering at each other.

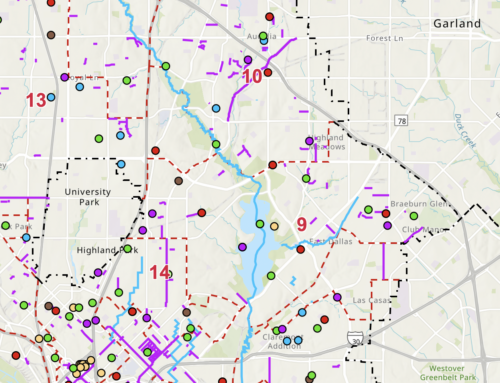

The focus of the meetings – the product of a concerned effort by Councilmen Mary Poss, Chris Luna and Craig McDaniel to give residents a voice in the decision – is a sound wall that the City and state have agreed to build on the east side of Central Expressway, somewhere between Fitzhugh and Mockingbird.

The meetings will help pin down exactly where the wall will be built. This is a question that has repercussions not only for the people who live there, but for the thousands of neighborhood residents who drive in the area.

First, there are engineering and construction considerations to keep in mind in determining where to build the sound wall. It doesn’t make much sense to put it some place where it won’t block the sound of traffic from the expressway.

But there are a host of neighborhood considerations as well:

• Which cross-streets will be closed and turned into cul de sacs. Some streets, such as McCommas, can’t be closed, since they are routes for emergency vehicles. Otherwise, the decision will come from a consensus established at these meetings.

• Which houses will be torn down. The wall needs land, and unfortunately, people live on that land. This is the sort of difficult decision that usually infuriates neighborhood residents, who rarely see how City planners make their choices. This time, residents cannot only see how it’s done, but can help make it.

• What the wall will look like. An ugly wall, or one that is too high or too low, could be as harmful to property values as if there was no wall at all.

• A host of other concerns, including garbage pickup, street maintenance and the like. If a street is closed, for example, garbage routes will have to be changed.

This progress in resolving thorny issues such as the sound wall and its traffic problems is called democracy. It’s a direct result of our current system of government, which has given the neighborhoods an increased voice in how their neighborhoods are governed.

There may be people who are unhappy with the results of the meetings. But no one can say they weren’t given the opportunity to influence those results.