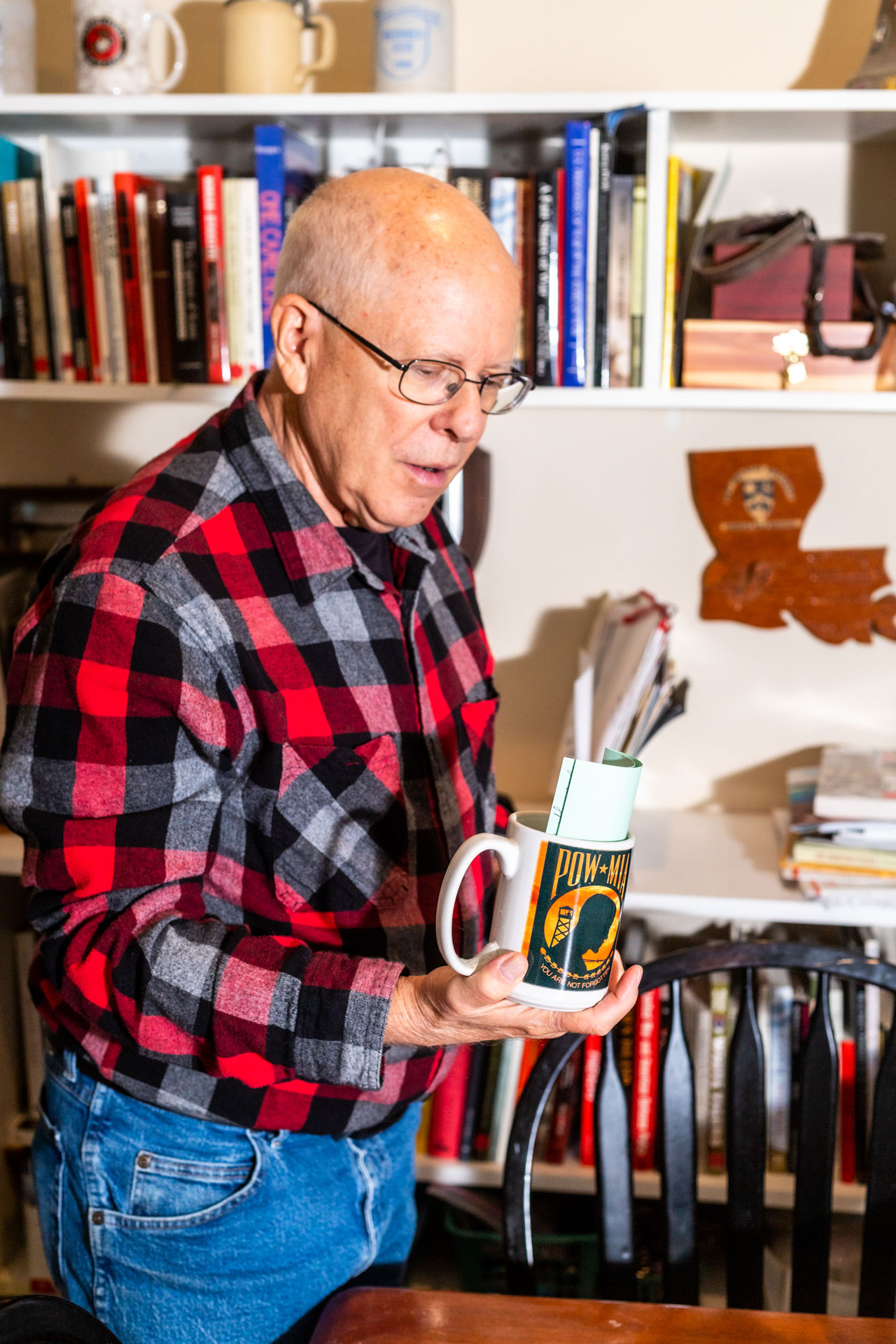

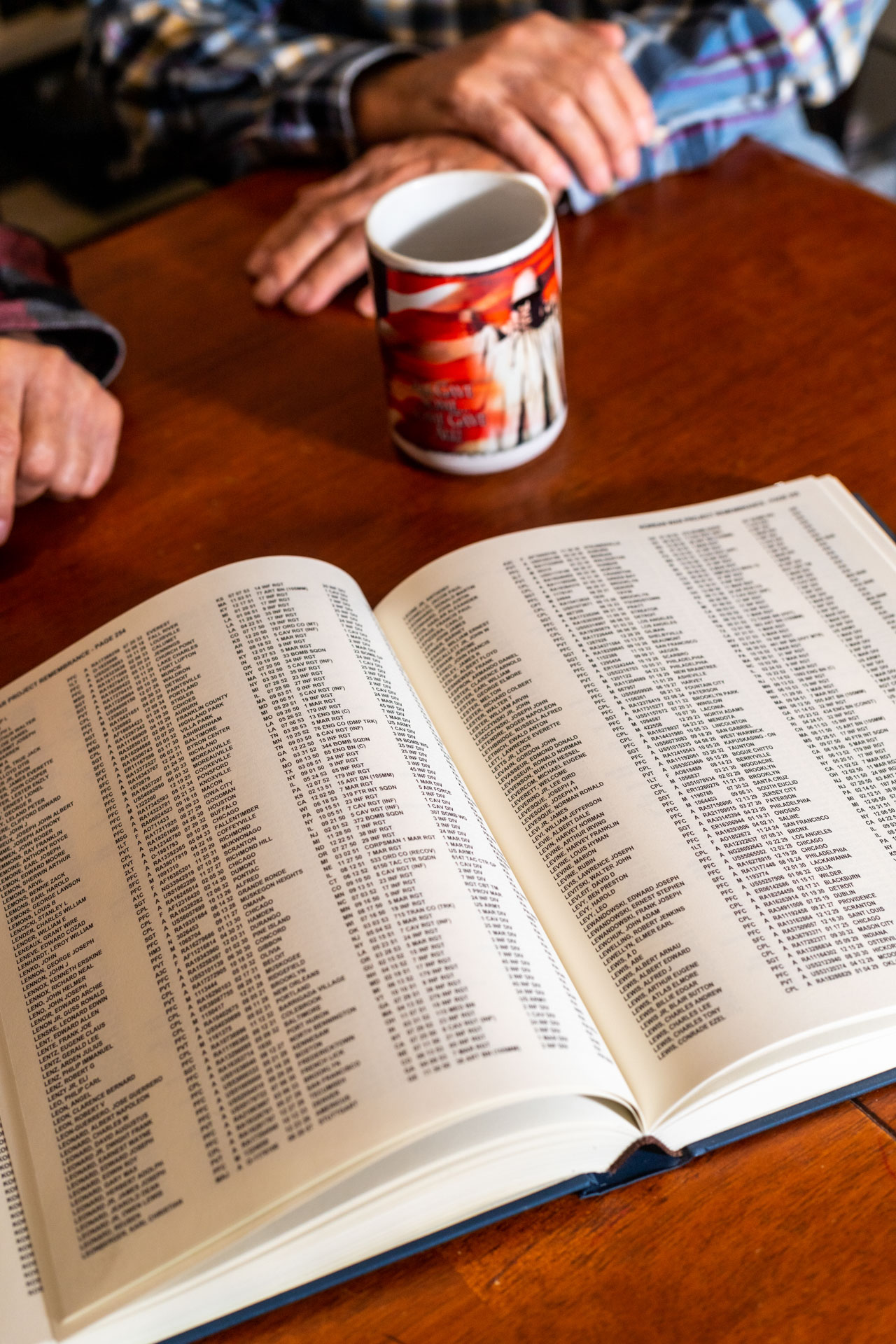

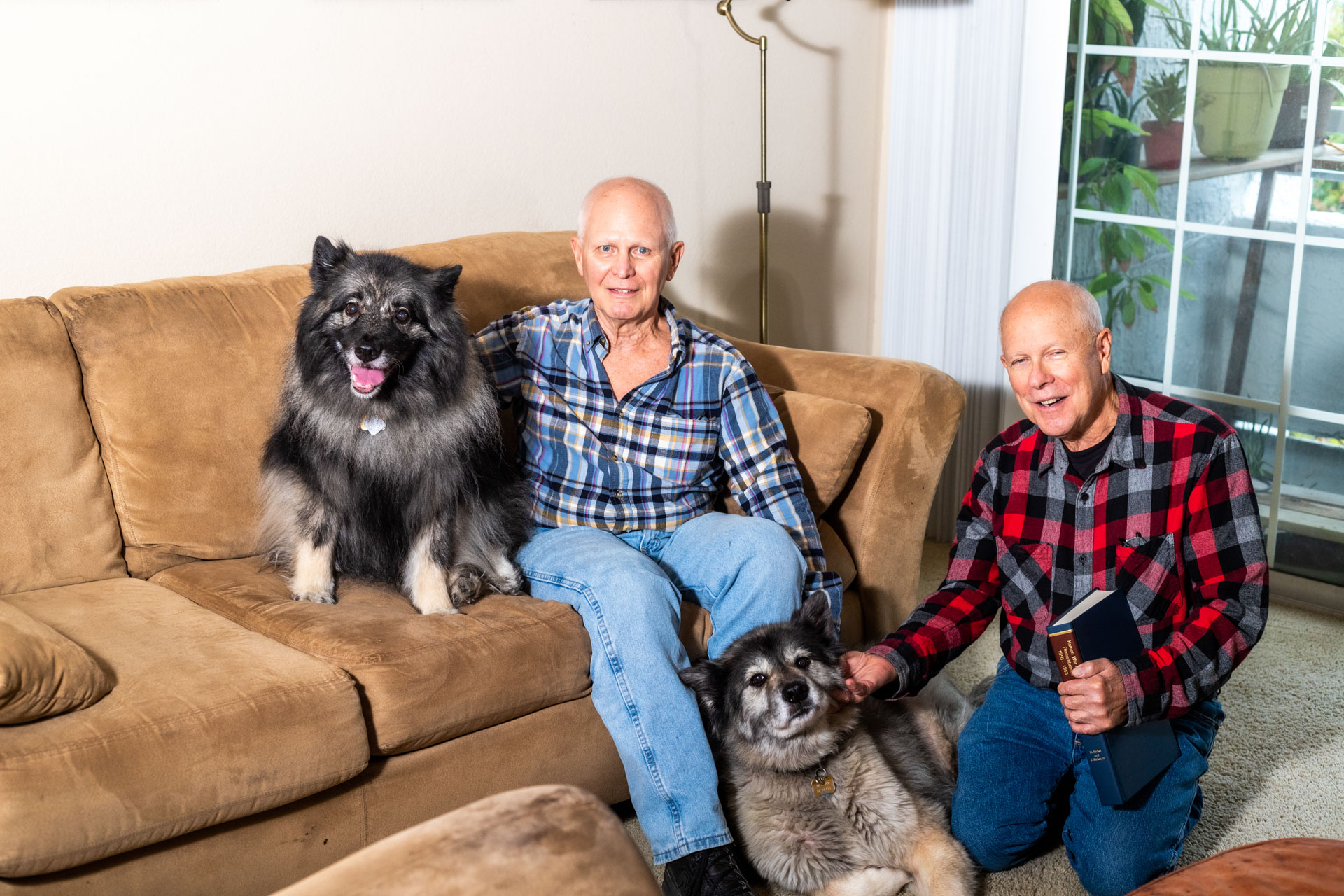

Hal Barker and Ted Barker sit with their published "Korean War Project Remembrance 1950-1953" book at their residence near White Rock Lake. Photography by Jessica Turner.

When Hal Barker asked his father about the Silver Star on his uniform in 1979, his questions were shut down immediately. His father, Marine Lt. Col. Edward Barker, told him never to mention the Korean War, often called the Forgotten War, again.

“So that immediately got me going,” Barker says. “I wrote the commandant of the Marine Corps, and about a week later, I got a letter saying that he had won the Silver Star at Heartbreak Ridge.”

Barker’s father, his aircraft hit and damaged in the October 1951 battle, made three attempts to rescue an airman who had been hit by friendly fire, only returning to base when he realized the task was impossible by helicopter.

The information left Barker’s curiosity about his father and the war unquenched. He ended up going to 24 reunions of the 23rd Infantry Unit and became an honorary life member of the unit.

Barker volunteered to join the military in 1967, the middle of the Vietnam War. His brother, Ted, had joined the Marine Corps. But Hal wasn’t able to enlist because he failed his physical. The cause was asthma, which he says developed after consuming contaminated drinking water at the Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, where his family once lived.

“Military kids go in the military because you don’t know anything else,” Barker says. “So that screwed up my whole career path.”

Barker got a degree in history from North Carolina State University, was a photojournalist and spent most of his career working as a carpenter. He has lived with his brother near White Rock Lake for decades. Throughout it all, he has kept his ties with Korean War veterans.

Barker’s dedication to helping them led to his involvement in safeguarding funds for a memorial, visiting Heartbreak Ridge — a hill inside the Demilitarized Zone, where no Americans had stood since the war — as a guest of the Korean minister of defense, creating a website about the war and the people who fought in it, and ultimately getting caught up in the politics of the Capitol, or as Hal calls Washington, D.C., a “snake pit.”

The Korean War Veterans Memorial Wall of Remembrance, which was unveiled in July, is meant to honor thousands of soldiers. Some of their names are spelled correctly. That’s significant to many families, who were able to take photos of their relatives’ names and place flowers in memory of them, Ted says. But what can’t be forgotten is that the people in power made an avoidable mistake with the new monument. Actually, it’s more like 1,400 mistakes.

“There’s no reason for it to happen,” Hal says. “It only happened because they didn’t want the two guys, Ted and Hal, getting the credit.”

The first iteration

When the Vietnam War Memorial was dedicated in 1982, Hal says he was the man the Korean War veterans called, asking why there wasn’t one to commemorate the war they fought in.

“So I said, ‘Well, I’ll go check.’ So the next time I went to D.C., I checked, and there was an organization fundraising, but they had some big problems, legal problems,” Hal says.

The National Committee for a Korean War Memorial, as it was then called, had lost its corporate registration and was raising funds illegally, Hal says. In a fact sheet presented to the United States Senate in 1985, the American Battle Monuments Commission writes the National Committee for a Korean War Memorial had collected over $300,000 in 1984, but none of that remained for construction of the memorial.

By 1985, Hal had started a trust fund, his $10 contribution the first donation. He and veteran Bill Temple traveled to Washington to advocate for their way of fundraising — which was making sure money went directly to the American Battle Monuments Commission, inaccessible to anyone except those with government approval. They made their case to Congressional aides in four minutes, two for each person, with Temple providing a veteran’s perspective and Barker pushing for safe harbor in a Treasury account.

Their elevator pitches convinced two Congressional committees to approve Barker’s plan, he says.

The Korean War Veterans Memorial was dedicated July 27, 1995, 42 years after the armistice ending the war was signed. Nineteen statues of members of the Air Force, Army, Marines and Navy are placed in the triangular Field of Service, advancing up a hill.

The Barkers weren’t invited to the dedication ceremony. Hal says he thinks it’s because the government didn’t want him and his brother to get the credit.

“That was highly disappointing but expected,” Ted says.

But the Barkers still attended as members of the public. Ted says he spent hours passing out water to other visitors, who needed hydration during the hot, humid day.

Creating the Korean War Project

In February 1995, the Korean War Project website went live. It was a single page, mostly detailing Barker’s 1989 trip to Korea.

The site drew traffic from the beginning. Some days, the Barkers say they would receive hundreds of emails from war veterans, then in their 50s and 60s, as well as their family members.

Soon after, the Department of Defense reached out, wanting help identifying the more than 8,000 people designated as missing in action. Hal wrote a program and put it on the website, while Ted worked the phones. They helped connect the government with families with whom they’d lost contact, allowing for the identification of thousands of people who fought in the war. And they did it as volunteers, receiving no compensation for their donated time or technical skills.

“It wasn’t for the government,” Barker says. “It was for the families.”

The Barkers kept adding to their website, and Korean War Project became a registered nonprofit in 1997.

Since then, Hal and Ted have spent almost all of their time on the project, collecting documents, resources, photographs, maps and other information regarding the Korean War. They still communicate with families, veterans and the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing in Action Accounting Agency, which works to identify missing personnel.

The wall

The Korean War Veterans Memorial Wall of Remembrance lists the names of more than 36,000 Americans and 7,000 Koreans who died in the war. Of those, Barker says, there are 894 misspellings and 540 missing. By his count, more than 37,000 Americans died in the war.

For comparison, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial had about 100 spelling errors.

The Barkers purchased the original Korean War casualty databases from the government in the early 1990s. They were called Records Group 330 and Records Group 407. After sorting through the names, manipulating the information into usable datasets, the Barkers could start verifying the spelling of each name by consulting gravestones, birth certificates, draft information, families and newspaper articles.

“We try to get confirmation of the name at least two or three ways, and we’ve been doing that now for almost 27 years,” Hal says.

Though the Barkers weren’t the only people trying to correct the mistakes, Hal says, they were the ones with a website.

Some of the errors they identified in the original data were caused by the way casualties were recorded. Soldiers’ names were typed first by companies or battalions. Each time the lists were retyped at various levels of the military, an opportunity for an error was introduced. A name might be shortened to fit a certain format, such as a punch card, which only allowed 25 spaces for names. Puerto Rican names, which use more than one family name, were often recorded out of order. The Barkers have also found that many Native American and Hawaiian names are incorrect.

Starting in 1998, the government combined Records Group 330 and Records Group 407. They worked on it for years, and eventually it became known as the Defense Casualty Analysis System 2008 file. This was the database referenced when compiling a list of names for the Korean War Veterans Memorial Wall of Remembrance, Hal says..

In 2014, when it was clear the government wanted to create such a wall, the Barkers were contacted by Bill Weber, the chair of the Korean War Veterans Memorial Foundation — the group responsible for fundraising for the monument. Weber asked Barker to give his casualty list to the foundation.

Barker, a career carpenter whose business revolved around contract work, wanted a contract in place first, to know his responsibilities and how the list would be used. He told Weber that there was still years of work to be done, but he received no response.

The next time Barker heard from Weber was in 2015, when Weber again asked Barker for the list. Barker again asked for a contract. He also wanted some form of compensation for the years of work he and his brother had spent compiling a list, rather than just handing it over, but there really weren’t any serious conversations about dollar amounts.

Barker says he rejected a $20 offer by Weber, who died in April, to cover the cost of mailing a copy of the database. He then mentioned funding for a book that he would print, not the government. His quickly conceived thought was that if there were sufficient funding for it, they could ramp up their research over the next few years. Weber told him he could only dole out $200, Barker says, so the book idea didn’t last.

Michel Au Buchon, a spokesperson for the Korean War Veterans Memorial Foundation, says in an email that because Weber is now dead, “any insight into what may have been discussed cannot be verified.” But James Fisher, the former president of the foundation, told Texas Monthly that Weber told the board the Barker brothers asked for $200,000 in exchange for their list. Barker says Weber created that number “out of thin air.”

Weber and Barker agreed that the Barkers’ list was “far more accurate,” as Weber wrote in a 2014 email to Barker, compared to the list the government would use for the wall and read during a ceremony. But the Barkers’ list wasn’t used.

“All I cared about is getting it right,” Hal says. “And what’s the most important part of a memorial list of names? The names. And what’s the part that they showed the least interest in? The names.”

The Department of Defense knew about some errors years ago, even as far back as 1998. Hal highlights an example from the Virgin Islands. According to the Wall of Remembrance, 76 Virgin Islanders died in the Korean War. By Barker’s account, only seven Virgin Islanders should be on the list; many of the rest are actually Filipinos or Canadians.

Barker wrote a letter to the National Capital Planning Commission in 2019, claiming that 36,574 was not the correct number of American forces who died in Korea and that there were over 1,000 spelling errors in the names to be inscribed on the remembrance wall.

In a commission meeting shortly after, the members discussed the letter. Col. Richard Dean, the vice chair of the Korean War Veterans Memorial Foundation, told the commission that the Barkers could release their list but wanted to be paid for their data.

One member asked if it was a “shakedown.”

“Could be,” Dean said.

Legislation passed by Congress mandates that the Wall of Remembrance at the Korean War Veterans Memorial should include the names of American military members who died in the war, as determined by the Secretary of Defense, as well as the number of members of: the Armed Forces of the United States; the Korean Augmentation to the United States Army; the Republic of Korea Armed Forces; and other countries in the United Nations Command who were killed, wounded or missing in action or were prisoners of war.

But visitors to the memorial wall can see that the names, not just the number, of the Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army, are included.

Names were compiled by the Secretary of Defense and passed to the Secretary of the Interior, who provided the list to the Korean War Veterans Memorial Foundation. Nowhere were the Barkers involved.

“To have these heroes’ names mangled is just very upsetting to me,” Ted says. “I try to control my emotions, but internally, I’m very, very upset.”

No surrender

About 18 months ago, Hal wrote to the White House, Secretary of the Defense and Department of the Interior, telling them about the need to fix the Defense Casualty Analysis System 2008 file and requesting a General Accountability Office audit.

Hal received an email in October 2022 from a representative at the Department of Defense, who asked for “any information that you can provide that would assist the Department in updating and correcting the Korean War Casualty List.”

But Hal says correcting that list won’t have an immediate impact on the wall. For the corrections to be made to the monument, the Department of Defense would need to issue a new database, and Congress would have to mandate some solution.

Hal has also filed for a Senate Armed Services Committee investigation into the misspellings, as well as the hundreds of dead soldiers the Department of Defense has refused to include in the Defense Casualty Analysis System 2008 file.

The dead include people such as Air Force Lt. Col. George Wellington Foster, who was from Dallas. In July 1950, Foster was piloting a plane that left Haneda Air Base in Japan and was headed to Itazuke Air Base in Japan on a courier mission. The plane crashed into the ocean about 64 miles southwest of Tokyo. The U.S. Air Force determined that Foster’s death, and the death of the others on the flight, were not war-related because the crash didn’t happen in the Korean War zone and the flight was not en route to or from the war zone.

Another passenger who died on that flight, Major Genevieve Smith, had been named the chief nurse for Korea by General Douglas MacArthur. Like Foster, Smith has been left off the wall.

“And so now we have the worst memorial in the history of the country, just because some guys didn’t want civilians involved,” Hal says. “Except, my brother was in the military.”