How name and route changes affect the former White Rock Marathon, and the marathon’s effect on the city

More than 40 years ago, fewer than 100 people ran the first White Rock Marathon, a 26.2-mile race that circled the lake a couple of times.

Over the years, the marathon has increased in popularity, blossoming into an event that accommodates 22,000 participants, transverses multiple neighborhoods, boosts the Dallas economy nearly $9 million per year and brings in charity funds also in the millions.

Growth doesn’t come without complications, however. From traffic issues to runners’ complaints to resistance to change, those associated with the marathon have seen their share of conflict.

For example, the race’s board of directors in May announced that the event was rebranding and would henceforth be the Dallas Marathon. The name change came on the heels of a location change from Fair Park to Downtown.

Organizers say the evolution is necessary in order to take the race to the next level. A top-tier marathon would be a financial boon to the city, organizers say, but big events bring logistical burdens. And not everyone thinks this historic race needs to evolve.

Reasons for the name change

There is some confusion about marathons in Dallas. Advocatemag.com commenters frequently mention the many marathons at White Rock and in East Dallas neighborhoods. However, there are only two sanctioned marathons in Dallas each year: the Big D Marathon in the spring and the White Rock Marathon (now Dallas Marathon) in the fall.

There are many other races, such as the Dallas Rock ‘n’ Roll half-marathon (March) and the Dallas Running Club half-marathon (November) and the Hot Chocolate 10k (December), but only two marathons.

Besides mileage, what is the difference? Typically, people will not travel to run a 10k or even a half marathon. In contrast, vacations often are planned around running a destination marathon.

One of the reasons for the name change is to avoid more future “lumping together,” says executive director of the Dallas Marathon Marcus Grunewald.

“From a strategic point, if we don’t use Dallas Marathon, inevitably someone will come along and start the Dallas Marathon. We want to be the destination marathon in Dallas. We own the rights to both Dallas Marathon and White Rock Marathon now, so we will avoid potential confusion there.”

In order to pull off the marathon, Grunewald and his team need the support of many city departments, as well as DART and local churches and businesses. The idea for changing the name came as the group discussed potential course changes with city staffers, says Grunewald, who ran his first marathon at White Rock in 1984, and ran another nine times before an injury kept him from running again. Then he became the race’s director.

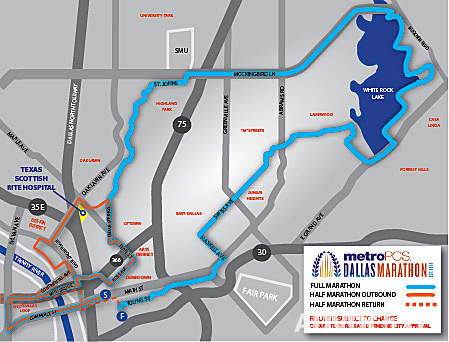

“We met with the city manager, and we talked about running the course by city milestones — the Arts District, the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge — and we got to thinking that this is bigger than White Rock Lake now. In fact, the half marathon doesn’t even see the lake. That’s where the process of changing it to Dallas Marathon started,” he says.

Some are disturbed by the decision to change the name.

“Dallas has no soul,” one Advocate reader writes on advocatemag.com about the name change. “It always is trying to be something else, some other city. Always on to the next shiny new thing.”

The name change signals a lack of pride in the marathon, says neighborhood runner David Renfro.

“In order for the marathon to be on the same level as New York, Chicago or Boston, the people of Dallas need to be proud of the marathon and show support for the race. Do you think the day after Boston people are complaining about traffic and not being able to get out of their driveways? No way.

“Here most people don’t even know about the marathon and are surprised when roads close, then they write into the newspaper and try and see what they can do to have the race canceled for next year. People here just don’t get it.”

Renfro, who has run three White Rock Marathons, says he believes the organizers took a step backward with the name change.

“I’m proud of the lake, and ‘Dallas Marathon’ doesn’t have the same feel. It’s not as personal to the city. One less thing to be proud of when it comes to this race.”

Others figure splitting hairs over a name is pointless while we could be arguing over more important things, such as the course. “I don’t think the name change will hurt anything; however, the course I detest,” White Rock Running Co-op member Michael Farrell says. “The long stretch of Mockingbird looks to be horrible. I will run since it is local, but I would not travel to this kind of course.”

The course

Change to the name, logo and course of our city’s oldest and largest running event could impact neighborhood residents as well as runners.

Always 26.2 miles, the marathon course has changed several times since its first run around and around White Rock Lake. It has seen starts at City Hall, Victory Park and Fair Park, and Dec. 9, it will return to a Downtown start. Every time the board makes a change, Grunewald says, it’s to make the race better. The changes have been based on both feedback from runners and requirements of the city, he says.

“The goal is to make this a better, not even necessarily bigger, experience for the runners.”

The city also receives feedback from residents and businesses, and sometimes changes are based on those comments, Grunewald says.

Planning the marathon course is an ordeal. First the board must submit an application to the office of special events. That department works as an umbrella over the other departments.

“Because of our size, police, DART, parks and recreation, traffic … we need approval from practically every city department,” Grunewald says.

The events office alerts each department, and then the marathon staff meets face-to-face with all of the involved departments to answer questions. (That session, for the 2012 race, had not happened at time of publication.)

Usually the official permit doesn’t arrive until weeks or days before the race, he says.

“Inevitably one department will always come up with objection at the last minute,” he says.

Marathon representatives meet with every church affected by the race. Last year, there were 20 along the route, and this year there are more. They also visit every business that is open Sunday mornings and every neighborhood association that might be impacted, Grunewald says.

Wouldn’t it be easier to just leave the course as is?

It would be simpler, he says, but there is still room for improvement.

“We have been aiming to get back to a Downtown start,” he says, adding that the city requested it. “It didn’t work the last two years, but now, with much of the construction wrapped up, it does.”

Will the starting point stay put this time? Hopefully, he says.

“But we don’t know yet what kind of feedback we will get after this race.”

It has been four years since the city manager, Mary Suhm, has met with marathon board members to discuss the event. Grunewald says the group has tried to set up such a meeting, but it wasn’t until this year it happened, perhaps because city officials now appreciate the race as an event that could boost tourism.

“A few years ago, we didn’t have 22,000 runners. We were not where we are now.”

Even if the city has not always fully embraced the marathon over the last four decades, it’s good to have the support now, Grunewald says. In addition to having city resources to put on the event, the city helps promote the marathon by placing Dallas Marathon information in Convention Visitors Bureau tourism materials. This will help promote the marathon nationally and internationally, Grunewald says.

I’m not a runner, so why should I care?

The New York City Marathon last November brought in some $350 million for the city, Mayor Michael Bloomberg told the press. Bloomberg gushes as he talks about the “magic of marathon day — the miles and miles of cheering spectators, the thrill of the race and the inspiring stories of the participants, the incredible hard work of thousands of volunteers who help make everything tick.”

If that’s the reach, Dallas has a long way to go, but New York is a good example of the marathon’s potential as both a moneymaker and a bonding experience for an entire city.

The Dallas Marathon last year boosted overall economic activity in the city by $8.7 million, according to a economic and fiscal study of the 2011 White Rock Marathon by two professors at SMU Cox School of Business. Spending by non-local race entrants and their guests is the most significant factor, according to the report. “When runners come to town for the race, they stay in the city for an average of 1.62 days and often bring companions with them. While in town, they spend money for lodging, meals, transportation, retail and entertainment.”

Additionally, the marathon employed 101 workers, and the city reaped an additional $264,000 in tax receipts. Countywide, the White Rock Marathon surpassed $11 million and supported 120 jobs, both full-time and seasonal.

Important to runners and non-runners alike is the marathon’s annual donation to the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for children. Earlier this year, the White Rock Marathon presented a check for $1 million to the organization that treats sick children free of charge. Since adopting the hospital as a beneficiary, the marathon has donated $2.8 million. Some say the course and name change are irrelevant when compared to the partnership with the hospital.

“The purpose of the now Dallas Marathon is to raise money for the benefit of the families and sick children of the Scottish Rite,” says Paul Agruso, a White Rock Running Co-op and Dallas Running Club member who plans to run the 2012 Dallas Marathon.

“The marathon is a nonprofit organization that wrote a $1 million check … I think that is something people lose sight of in this whole discussion or disgust generated from the name change. If they think they can raise more money for the Scottish Rite by changing the name, then I am willing to give them the benefit of the doubt to try it.”

In addition, a better race can boost the city’s image, according to the SMU report.

“The race receives wide local and national media coverage. Though impossible to quantify, the value of this publicity is substantial, and it generates a sizeable amount of positive PR for the city and the region.”