The shotgun duplex at 3111 N. Winnetka is the site where Clyde Barrow made himself infamous.

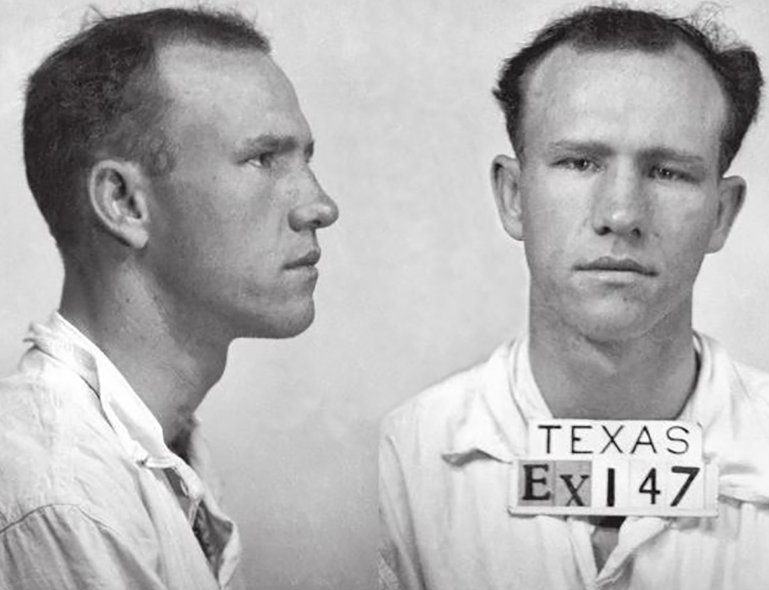

It’s where he wound up killing Tarrant County sheriff’s deputy Malcolm Davis in a case of bad timing. After that, Barrow became a well-known fugitive from justice, culminating in the violent deaths of West Dallas outlaws Bonnie and Clyde less than a year and a half later.

The building is still standing, barely, but it’s not long for this world. The privately owned Wesley-Rankin Community Center owns the building, known as the Lillie McBride house because of its place in the history of Bonnie and Clyde.

The nonprofit wants it demolished or moved because it’s been broken into multiple times, says Wesley-Rankin executive director Shellie Ross. The break-ins “raised safety concerns for the community we serve,” she says. “Our board decided to either demolish the house or have it removed from the premises.” Ross says they haven’t come to any agreement about the house, and they’re weighing whether to move or demolish it.

It’s not just a coincidence that a nonprofit meant to serve the impoverished residents of West Dallas happened to own the Lillie McBride House. The Barrow Gang and a Swiss Avenue neighbor actually played a role in the history of the nonprofit, but more on that later.

First, here’s what happened at the Lillie McBride house, according to Jeff Guinn’s 2009 book, “Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde.”

Few places in West Dallas tell the story of the Barrow Gang as well as this one.

It’s a few blocks from the Barrow Filling Station, Clyde’s family home on Eagle Ford Road, now Singleton Boulevard. He grew up with Lillie McBride, who was the sister of Barrow Gang member Raymond Hamilton.

On Jan. 6, 1933, six lawmen were lying in wait at the McBride house for Otis Chambliss, a West Dallas criminal who was cozy with McBride, because Chambliss had robbed the Home Bank of Grapevine about a week before.

Around the same time, Barrow was scheming to break Hamilton out of jail by having his sister smuggle hacksaw blades inside a radio she’d brought to him in the Hillsboro jail. That night, Barrow dropped by her house to ask if she’d done it.

When Barrow walked up, armed with a shotgun, McBride’s sister, who knew the cops were there, screamed for no one to shoot because her children were asleep in the house.

Barrow immediately started shooting, and he killed Davis, who was 51.

Barrow managed to escape, and Bonnie drove around and picked him up on the next block. They headed west on Eagle Ford Road and out of Dallas.

Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker were killed in a law-enforcement ambush on May 23, 1934. By then, they’d fallen out with Raymond Hamilton. But he was a bad guy in his own right.

Here’s how the dastardly legacy of the Barrow Gang led to the creation of the Wesley-Rankin Community Center.

In 1935, church worker Hattie Rankin Moore read a newspaper story about Hamilton, who was condemned to die by electric chair. Moore was moved by Hamilton’s mother’s grief, so she went to visit her in West Dallas.

Moore prayed with Hamilton’s mother and family. She sat with them on the night of his execution and arranged his funeral.

Moore, who lived on Swiss Avenue but had spent years serving impoverished communities in San Antonio, rented a house in West Dallas and offered church services to people in the neighborhood. She went door to door in the city’s worst slums recruiting neighbors to church services. Her church, Eagle Ford Mission, grew to about 100 members, and even Clyde Barrow’s mother, Cumie Barrow, attended.

At a time when even police officers avoided West Dallas, Moore taught Sunday school classes in the backyard of the home of Floyd Hamilton, the younger brother of Raymond Hamilton. Floyd Hamilton was also a criminal who did time at Alcatraz.

At a time when even police officers avoided West Dallas, Moore taught Sunday school classes in the backyard of the home of Floyd Hamilton, the younger brother of Raymond Hamilton. Floyd Hamilton was also a criminal who did time at Alcatraz.

After four West Dallas boys who Moore knew were charged with murder for beating a man to death, Moore was determined to start a recreation league to give neighborhood kids something to do other than make trouble.

She wrote in a letter to the editor: “Folks wonder why so many West Dallas boys turn out to be criminals … they haven’t a dog’s chance to be anything else. We have no parks, no playgrounds, no handy schools, no lights, no water, no gas. The dogs in Dallas are housed better than our boys and girls.”

Eagle Ford Mission eventually was renamed Wesley-Rankin Community Center, which is a member of the North Texas Conference of the Methodist Church. A nearby city of Dallas park was named in her honor.

The Wesley-Rankin Community Center continues to serve West Dallas residents of all ages, offering after-school care and summer programs for children, GED and ESL classes for adults and activities for seniors. Find more information at wesleyrankin.org.