The state of Texas has cut education spending drastically. The Dallas school district has more failing schools than are rated Exemplary by the Texas Education Agency. And sometimes it seems like all the youth of America is going the way of TV’s “Jersey Shore.” That is, they’re narcissistic, promiscuous and disrespectful of themselves and others.

But all of America’s youth are not trashy reality-TV character wannabes. Some of them are great kids, even in the face of adversity.

The following stories showcase a few delightful neighborhood students who have overcome the odds to become successful, college-bound high-school seniors. They prove there is hope after all.

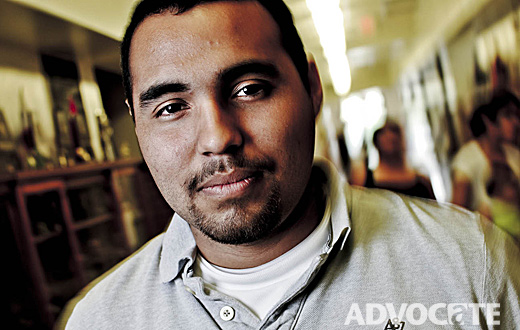

Luis Veloz

If you can learn to love people, you can change the world, Luis Veloz says.

Over the past four years, Veloz says he has realized that love is the most important thing. Now he’s ready to change the world.

The 18-year-old Woodrow senior is from our neighborhood, but from the ages of 6-14, he and his family lived in Mexico. When he returned to Texas in eighth grade, he says it was a scary time.

“I was a very shy boy,” he says.

But a couple of years ago, he attended a symposium for Hispanic youth at the SMU Cox School of Business. That’s where he learned about servant leadership, giving of yourself to make the community better.

“I came out a changed man,” he says. “I found my passion.”

He realized there were students in his school who were under-represented. So he started a LULAC club. Then he realized that the LGBT community wasn’t represented. So he started the Gay/Straight Alliance. That club, which works on anti-bullying efforts and fostering tolerance among all students, has spread throughout high schools in Dallas ISD and other districts, including Irving, Frisco and Plano.

Now Veloz wants to study business and become a lawyer to fight for social justice causes. He’s also considering Teach for America after college.

“I just want to help people in any way possible,” he says.

It’s extraordinary that an 18-year-old would make the effort to change his world for the better, says Miguel Esparza of Education is Freedom, who helped Veloz with college applications.

Veloz’s dad was a carpenter, building staircases in new homes, and he hasn’t worked much since the economic fallout four years ago. Now he earns extra money for the household as a shade-tree mechanic. Veloz’s mom works two full-time jobs in food service, often putting in 16 hours a day.

“Everything I do is for her,” Veloz says. “I tell her, ‘One day, mom, you won’t ever have to wash a single dish, clean another house or wait another table.’ She’s given up so much for me.”

Learning to love his fellow students and to receive their love in return has been the most life-changing part of high school, Veloz says.

“They call me ‘lover boy’ because I’m always drilling that — love, love, love one another,” he says. “I do want to change the world, and I’m not going to stop.”

Samantha Braun

Samantha Braun is a blonde-haired, blue-eyed cheerleader who also plays on the golf team at Woodrow Wilson High School. She has her own car and a closetful of cute clothes.

At first glance, it could be easy to stereotype her as preppy, privileged rich girl. But a closer look reveals this: Braun is an A student with two part-time jobs and more responsibilities than most 18-year-olds.

She saved up money working at J. Crew in NorthPark Center and babysitting to buy the 2003 Mitsubishi Eclipse she drives. Braun’s parents divorced in 2008, and soon after, she moved to Dallas from Florida with her mom and three siblings.

Her dad has struggled to find work in the tough economy. Her mom is a graduate student at the University of Dallas who earns about $17,000 a year running a small business. Braun and her 17-year-old sister work and take care of their younger siblings, picking them up for school and shuttling them to practices. They buy their own clothes, pay their own auto insurance bills and everything else, including the $900 a year each it costs to participate in cheer, for example.

“It’s been hard having to be independent,” Braun says. “It’s taught me a good lesson, and I feel like I’m prepared for college because I’ve already paid for everything on my own.”

Braun is ranked 11 of 354 seniors at Woodrow, and she is a leader, often organizing events such as a powder-puff football game in April.

“I never have to worry about her,” says cheer coach Brook Varner. “If there’s an event we’re planning, she’s on top of it. I don’t have to worry about anything, and that’s every rare for a student.”

Braun also has served as a student council representative and is a copy editor on the yearbook. She was a national Questbridge Scholarship finalist but decided to go to Texas A&M University because she has scholarships equating to a full ride there.

“A college education will make it possible that I never have to go through what I’ve gone through the past two years,” she says. “That’s just the way I’m wired, is to be the best that I can at whatever I’m doing.”

Dayna Martin

Dayna Martin is only 17, but she already has a very specific, grown-up career goal.

“I really want to work at the Frito Lay National Headquarters,” she says.

Martin, who is a JROTC leader at Woodrow Wilson High School, visited Frito Lay with the Women of Color Multicultural Alliance last year. As part of the visit, she played executive for a day, and she loved it.

“I think that’s the thing to do, work at a really big company like that,” she says. “That would really show my parents and my family that I can do more than they expect.”

Martin was born and raised in our neighborhood, but her parents are from Mexico. They married and had kids as teenagers, and they’ve always struggled to earn enough money. Martin’s dad is a laborer for a sign company, and her mom works in an elementary school cafeteria.

“No one in my family goes to college, so they never have good jobs,” Martin says.

Her parents want her to go to college, but she says their expectations are low. Martin’s expectations for herself are very high. She is an A student and has been awarded the $20,000 Century Scholarship from Texas A&M University, which also includes study abroad in Europe. Add to that other scholarships, including $1,000 and a laptop from Frito Lay, and financial aid, and Martin says she has a full ride. JROTC director Edwin Dumas says Martin went the extra mile to apply for every scholarship she could find.

“She’s the perfect example of what you can do if you really work toward it,” Dumas says. “Nobody’s going to knock on your door and ask if you want a thousand-dollar scholarship. You have to look for them, and you have to be your own best advocate as far as getting good grades.”

Aside from her responsibilities at school and in extra-curricular activities, Martin takes on responsibilities at home, helping younger siblings with schoolwork and making sure they wake up, eat breakfast and get to school on time. She always has been a good student, she says, and she skipped third-grade because teachers thought she needed more challenging work. Academically and professionally, she says, she has something to prove.

“I want to prove others wrong,” she says. “People tend to see young Hispanic girls drop out or get pregnant at 16, and I want to change that stereotype that people have of Hispanic culture.”

Emmanuel Hernandez

Emmanuel Hernandez knows he wants to work for a big accounting firm, and the 17-year-old is headed to Oklahoma State University for a five-year program there.

Hernandez, who grew up in our neighborhood, had an internship at Price Waterhouse Cooper through the Mayor’s Internship Program last summer. His eyes light up when he talks about it.

“I got to do an audit simulation,” he says.

Accounting might have the reputation of a dry, boring profession, but Hernandez says he enjoys the exactness of it, the excitement of finding a mistake.

Hernandez is the only child of a single mom who cleans houses to support them.

“I’ve seen the struggles that my mom goes through. I don’t want to go down that path,” he says. “I want to live somewhere better.”

The varsity soccer player says he feels lucky to have gone to Woodrow.

“There are a lot of smart kids here. There’s great competition, and it pushes you to do more and work harder,” he says. “A lot of people underestimate Woodrow, but it’s a great school, and it’s only going to get better.”

Gabriel Galarza

Gabriel Galarza knows how to pull an all-nighter. Two years ago, the 18-year-old started taking extra shifts at the Tex-Mex restaurant where he works because his dad was ill. His mom had been laid off from her job in a meat-processing plant, so Galarza and his brother worked seven days a week bussing, washing dishes and waiting tables to earn a collective $1,100 a week to support their family, including a younger sister.

During that time, Galarza regularly stayed up until 5 a.m. doing homework after his shift at Cantina Laredo. That went on for six months, and around that time, Galarza also rededicated himself to schoolwork.

A math whiz and A-student throughout elementary and junior high, Galarza started slacking during his freshman year, he says, earning Bs and Cs. When his dad was sick, Galarza says he felt more adult, more responsible.

“If I feel lazy [in school], that’s how I’m going to feel in the future,” he says. “I just want to be a hard worker.”

As a senior, Galarza has early release from school and works 27 hours a week.

“He’s always working,” says Ashley Dancer of Advise Texas, who helped Galarza though the college application process.

He was accepted to several universities, but decided to stay close to home and attend the University of North Texas. He plans to take night classes in business and entrepreneurship while working during the day, of course.

“I want to have a career,” he says. “I want to get a big house and have my parents live with me.”