Larry Offutt, Anne Courtin, Harryette Ehrdhart, Virginia McAlester and Martha Heimberg gather at one of the entrances to the Swiss Avenue Historic District, which they worked to establish. Photo by Can Türkyilmaz

The Swiss Avenue Historic District set a trend for preservation in Dallas

The commercial and residential developments that line Gaston aren’t entirely postcard worthy. As Old East Dallas started to decline in the ’70s, neighbors began taking steps to protect the grand mansions of Swiss Avenue. The elegant houses with side porches and antique carports are evidence of a different era in Dallas’ history.

Residents living in homes that are now part of the Swiss Avenue Historic District were able to save the 19th century homes from destruction by rallying together. Though the foremothers and forefathers of the Swiss Avenue Historic District came on the scene at varying times — some in its heyday, some after homes had fallen into disrepair — they all shared a deep love for preserving their neighborhood.

This month, five residents who fought the good fight share their stories of why the avenue’s grand mansions are still standing and as beautiful as ever.

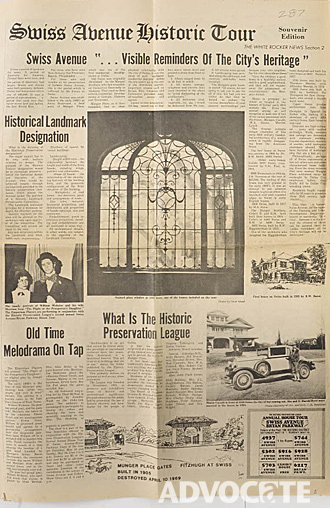

Harryette Ehrdhart held onto this souvenir edition of the1974 Swiss Avenue home tour. To find more historical Swiss Avenue documents, visit lakewood.advocatemag.com/photos.

When Harryette Ehrhardt and her family moved into a house on Swiss Avenue in 1970, they shared the space with a commune of hippies. “Back then in the ’70s, when we bought the house, people didn’t bother to turn their water, electricity or their gas off cause it didn’t cost very much. So there were squatters. They just came in and lived here, and they never paid any rent.” After closing on the house, Ehrhardt says she tacked a note on the front door telling the squatters that her family had bought the house, but they could live in the back. In June, she decided it wasn’t smart to have squatters in the back house, so she left a note saying they would have to move out.

Martha Heimberg moved to Swiss Avenue in the early ’70s. “These cavernous places were being sold for very low prices. Not low to us then because we were young, but lower than anything else we had seen. The whole neighborhood looked like it was from another world. The houses in the Park Cities, some of them were old, but not as old as you know… Swiss Avenue was built in the teens, ‘20s. A few [houses were built] in the ’30s. To see that many together for the first time was … you felt like an archaeologist.”

When he was a paperboy, Larry Offutt delivered newspapers along Bryan Parkway, Swiss Avenue and Live Oak Street. Offutt grew up in a house on Bryan Parkway and attended Lipscomb Elementary. “I’d always lived in the neighborhood. My first apartment after moving from my parents’ house was to a garage apartment on Swiss Avenue. My second one was to an apartment two blocks up on Ross. And then the third one was to one block up on Gaston. So I always lived in this neighborhood.”

Virginia McAlester’s family has lived in the same house on Swiss Avenue for three generations. Her parents, Wallace and Dorothy Savage, were founders of the Historic Preservation League, known today as Preservation Dallas. “I’ve actually lived in five different houses in Swiss Avenue, one of them down Peak’s Suburban, below the gate. It’s where I lived when I was a little girl. And then I lived in a house next door. When it had been turned into apartments and had refrigerators on the front porch and a car jacked up in the front yard, my parents said, ‘Oh, we have to buy this house.’ So my husband and kids and I lived there, fixed it up and got it back to some semblance of order.”

E.L. Dunn rented a house on Swiss Avenue before the district was formed. “I’m an architect, so the value of the homes on Swiss Avenue was quite evident to me.”

Early life on Swiss Avenue

In June 1857, Swiss immigrants moved to East Dallas. In their honor, their countrymen named the street where they settled “Swiss Avenue.” In 1905, developer R.S. Munger decided to use Swiss Avenue and several nearby streets for a new residential area. The 140-acre project named Munger Place was built between 1905 and the mid-1920s. It soon became the neighborhood of the early movers and shakers of Dallas.

Ehrhardt “The first people who lived here were very well-to-do. They had carriage houses. The steps on our carport were not for cars at all but for carriages. They had gas sconces because they weren’t real sure electricity would be here to stay. Those individuals all had lots of people who helped take care of the houses. It took three full-time people to maintain my house.”

McAlester “The original part of Swiss was simply the first two and a half blocks. The section from Skillman up didn’t open until after 1920. When my mother moved here in 1921, they had a cow named Bessie that lived in the little shed in the garage. Every day, they walked her above Skillman and put her out to pasture because it was just fields up there. Hard to imagine.”

Dunn “After World War II, the housing shortage in Dallas was monumental. There were not places for people to live. The houses on Swiss were getting to be 20 and 30 years old then. Some of the people in higher income brackets were beginning to move to the Park Cities. The need for housing caused some of those houses to be subdivided and rooms were rented out to meet the housing shortage. Some of the houses were divided into numerous apartments.”

Ehrhardt “The original owners were getting older. The houses were hard to maintain, and people did not really want to have three servants. That was more expense than they wanted. The houses didn’t have the push-button convenience that a new house can have.”

McAlester “It was in such bad shape that no one wanted to build anything over here anyway. It was all red-lined. It was just going down, down, down every year. You couldn’t get a loan for a house because it was zoned for apartments.”

The beginnings of the movement

One evening in 1971, nine neighbors met at the home of Wallace and Dorothy Savage. Wallace Savage was a former mayor of Dallas, and at the gathering, two architects, whom Savage had hired to report on the architecture of the neighborhood, presented information that confirmed that the neighborhood was worth saving. During the meeting, Savage shared a vision to protect the neighborhood from what everyone expected, demolition. McAlester remembers her mother coming home in tears after hearing another house was going to be torn down at a zoning hearing.

McAlester “Everything, everything from Central Expressway over to Interstate 30 out to the Lakewood shopping center was zoned for apartments then. So the common wisdom was that everything would be demolished. The idea that we could save some of it and save some interesting neighborhoods was like an electric shock went through my body. It was like, oh wow! Something positive can happen besides all this stuff being demolished.”

Offutt “What we were attempting to do is block the change of zoning from single-family to multi-family. Actually, parts of Bryan Parkway had already been rezoned to multi-family. Swiss, because of the deed restrictions, hadn’t been. The historic designation piece we just happened on by accident as a way to stop that zoning.”

Ehrhardt “There was no such thing as a historic preservation league. There was no such thing as a city ordinance for historic preservation. There was none of that. Those weren’t even words we ever heard of before. So we decided that we would go to City Hall, and we would ask them not to build a post office at the end of the block because we wanted this to be a historic district, and they literally laughed at us. This would have been in ’71. They said ‘What are you talking about? Developers have been buying that property for years and years with anticipation of putting high-rise apartments there. There’s no way.’ So we came back here in this living room and were near tears, mainly because we didn’t like to be laughed at. Somebody said, ‘Well, I guess you just can’t fight City Hall.’ Somebody else said, ‘Well then, we’ll just become City Hall,’ and we proceeded to do that.” We had two big problems of getting this district made into a historic district. The first one was to convince the city council, i.e., the city of Dallas. Equally difficult was to convince the people who lived on Swiss. The developers had really put the scare tactic in. They would tell older people that if this was a historic district, you couldn’t have anyone living with you, and a lot of them had boarders at that time who were for income but also to help them with their house. They also said you’d lose your house because it’d cost you thousands and thousands of dollars to fix it. And you wouldn’t be able to do anything to the interior of your house. You wouldn’t be able to rewire it or do anything. And you would have tour buses going up and down the neighborhood.”

Offutt “It was a door-to-door process, over and over, both talking to people and handing out materials and calling block by block meetings and winning over people one household at a time. Both people in a household weren’t necessarily for it, so I mean, it was truly a controversial thing at the time.”

Ehrhardt “Every Sunday afternoon there was no Cowboys game, we would walk. Each of the 11 of us had a portion of what we would later be the district. Our job was to convince those homeowners, and so we would give them brochures saying, ‘You will be able to have anyone living in your home. The historic ordinance will only affect the exterior of your home, nothing about the interior. You will not be made to put any money into your home. You can leave it just like it is. And you will not have tour buses going up and down your street.’ Well, all of that was true except for the tour buses part. And every time there is a tour bus that goes up and down the street, I’m like, ‘Ugh, I thought I was telling the truth.’ I always feel very guilty every time I see a tour bus that goes down the street.”

Offutt “At that time the growth had started out to North Dallas, and many of our civic leaders that had lived here had already abandoned the inner city to go north into the new development. To back zone something to single-family was just, nobody had ever heard of anything like that in Dallas at that point. That actually is where the greatest resistance came from. Property owners were anticipating being able to sell these residential lots for four, five, six times the purchase what they thought they would be able get if they sell it as a single family home. So there was a lot of resistance from residents who were here at that point who were anticipating a big sell-off and really pocketing lots of cash, which you can understand. For many of them, that was in their minds — their retirement, their nest egg. So you can certainly understand why they felt that way and why they felt so strongly about it. But it was just a matter of convincing people that their property values could not only be maintained but go up.”

Ehrhardt “The tour was one of the first-year plans to convince people that we needed to have a district. The first tour predated us having a historic district, and our house was on tour. We expected a few hundred people maybe. We had 2,500 people that first weekend.”

Heimberg “During the first tour, we wore period clothes. Dorothy, Virginia’s mother, had kept a big wardrobe filled with her mother’s clothing. There were wonderful furs and beautiful lace dresses. So our first house tour was not only opening our houses but playing dress up. The tour, which took place in the vicinity of Mother’s Day, maybe it was Mother’s Day, was ridiculously successful.”

Ehrhardt “The [historic district] ordinance was written — it was based on the New Orleans French Quarter ordinance — and then we set up a meeting at City Hall. Each of the 11 of us had a different point of view. Somebody did architectural significance, and somebody did the importance for the aesthetics of the city, and I don’t remember what all, but we had 11 points that we made. And ours, Dr. Ehrhardt and I, was that we wanted our children to go to our schools and if they were destroyed, we wouldn’t have these schools for our children. Our children deserved to have a historic district that their children and their children’s children would be able to know was in a historic part of Dallas. So we took our children out of school, and at that point we had five, and we looked like a mother and father duck with ducklings behind us. Each of the 11 of us had exactly two minutes, and each of us had our two-minute speech down just like this [snaps fingers]. It wasn’t one second over two minutes. And we did them exactly right. We were so good. The council just fell all over themselves voting for us. It was a unanimous vote. I mean, nobody said anything. Even Crownrich, [a developer] who had bought much of this to build his apartments, didn’t even bother to speak. There was one woman who lived on the end of Swiss in the only house that doesn’t look like ours, and that woman was the only person who spoke against it. Everyone else on Swiss Avenue was for it. I mean, it was like Christmas and Halloween and Valentine’s Day all rolled in one.”

Offutt “The original name of the historic district was the Swiss Avenue Bryan Parkway Historic District. That got changed later. People tend to forget that. Even people who have lived here many, many years who weren’t here during that initial struggle don’t really understand that there could not have been a historic district if these two blocks on Bryan Parkway had not joined.”

Life in the historic district

After being named Dallas’ first historic district in 1973, the planners and organizers made it their mission to establish historic and conservation districts throughout the rest of the city. Today, Dallas has more than 15 historic districts.

McAlester “One of the first things we did after we became a historic district was we went to South Boulevard and Park Row, which is over near Fair Park. There is a three-block stretch over by the interstate. My house was modeled after a house over there. It’s much grander, actually. We thought it was important that many parts of town become historic districts and protect their resources.”

Offutt “We were landlocked, essentially, in our neighborhood because we’d already lost Gaston. We’d already lost Live Oak. So we were landlocked. We needed to grow that area to other areas to continue the whole piece of the inner city and preserving this part of our city and our area in history.”

McAlester “What I didn’t realize then is that we were basically recycling on a major scale. Lots of people recycle their aluminum cans or their printer paper or whatever, and not many people really stop to think about how much energy and materials and timber are embodied in every single structure. I could recycle for the rest of my life and barely equal the waste and the landfill if you tear down one large house. “

Offutt “The historic district and the inner city are still under a constant siege. We can’t let up ever in terms of paying attention to what’s going on in City Hall or what somebody wants to move in and do. We’ve found over the last several years the city is much less friendly to the inner city historic districts and conservation districts than they have been in the past. We constantly have to battle to protect ourselves in the neighborhood.”

Ehrhardt “Saving Swiss Avenue got our family interested in politics. That’s why I served on the school board and later in the [state] legislature. It was to impart to people if you want to save your neighborhood, you can do it. We turned this around. It is possible to do that.”

Interviews have been condensed and edited.

Find more historical images at lakewood.advocatemag.com/photos.

Swiss Avenue’s annual Mother’s Day home tour is on Saturday and Sunday, May 12-13.