The Ultimate McMansion? Or a White Rock Lake Renaissance?

Fit and tan in his mid 40s, the blond, impeccably dressed Mark Miller is quick-witted and likable, arguing passionately for his product to a largely skeptical, and at times, hostile audience. But no matter how contentious the crowd becomes, Miller keeps his cool. In fact, the more heated the debate, the more he appears to be in his element.

“I’ve been told everyone here is in favor of the project,” he quips at one point in the meeting.

In sales parlance, he’s a closer — the guy you put out in front of the client to seal the deal. When the product is a $50-million high-rise towering over White Rock Lake and the established neighborhoods surrounding it, the salesman better be pitch-perfect.

And he is — almost.

The Project

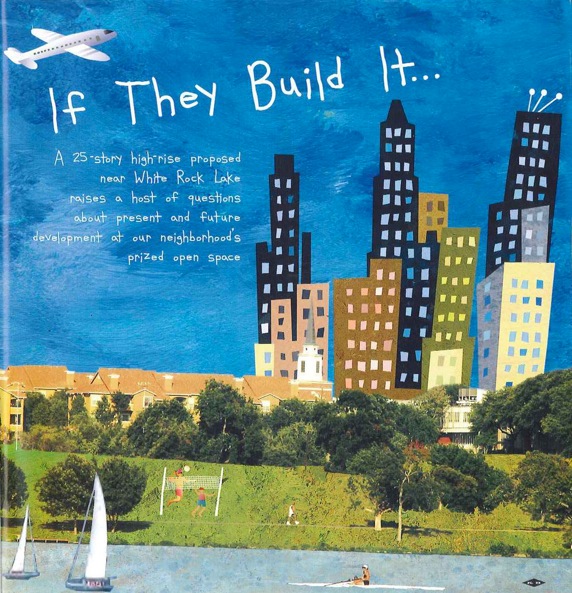

Just as high-rise living has swept Uptown, Downtown, Mockingbird Lane and even Addison, so it has washed up on the shores of White Rock Lake. Miller and partner Leon Backes have formed Emerald Isle Partners L.P., and envision a 25-story luxury condominium high-rise that will revitalize the area and restore our neighborhood to its past grandeur.

But some residents look at the development plan and envision a steel and glass “one-finger salute” (as described by one attendee at that same meeting) visible from every point on the lake forever.

The debate is in its early stages. While the developers have conducted numerous private discussions with area business owners, the project was first introduced to the public recently at what was supposed to be an exclusive forum for Little Forest Hills residents. Word quickly spread, however, and despite the short notice, a standing-room-only crowd of nearly 200 residents from various neighborhoods surrounding the lake — Emerald Isle, the Peninsula, Forest Hills and Little Forest Hills — came out in force to find out more about the project.

The developers need the support of the community. The deal hinges on their ability to change the zoning of the two-acre lot at 1000 Emerald Isle, roughly between the lake and Barbec’s restaurant on Garland Road, from Community Retail to Multi Family. Without the zoning change, the project can’t be built.

If the response at the recent meeting is any indication, it will be an uphill climb.

Or as one area homeowner put it: “You’re going to get some fire out of this.”

The Hype

Miller has an ace in his pocket. He was born and raised in East Dallas and has been an avid runner at White Rock Lake for decades. This allows him to speak eloquently about his connection to the area and his hopes for its revitalization.

“You know what? I live there, I run there, I work there, and I want to stay there,” Miller says.

“What has really bothered me is the stagnation and decline of Garland Road. The neighborhoods along there are charming, but the businesses are not reflective of the area. This is, for me, a very rare opportunity in life for my passion and a business opportunity to unite.”

His plan is to “drop a big rock” in the neighborhood, creating ripples of economic development that could reach Casa Linda Plaza to the north and south to East Grand and Gaston Avenue. What the area needs, he says, is its own identity, similar to Uptown or the Arts District. The Emerald Isle high-rise would be a “beacon for all of East Dallas,” he says, and the anchor for future development and investment in the community.

That’s the long game.

In the short term, area restaurants and retailers would benefit from the addition of 185 to 225 high-end residential units and the 500 or so new residents shelling out upwards of $300,000-$1 million for each condo unit. As the theory goes, other retailers and restaurateurs would take notice, resulting in an influx of more desirable businesses than the nearby tattoo parlor and dollar store Miller frequently cites as proof of the area’s decline.

In addition, millions of dollars in Texas Department of Transportation money would become available for improvements to Garland Road once the area begins its transformation, Miller says.

“But those funds are only available if you show a turn in the area — renewed interest, new development, revitalization.”

He’s also quick to point out the increased taxable value of the property once $50 million worth of improvements are made to the site, which he estimates would be $2 million a year in property taxes to the city of Dallas.

The Goods

Miller’s presentation is polished. But a closer look begs a host of questions.

First, how dire is the situation along Garland Road and Casa Linda Plaza, and is a 25-story high-rise the only, or best, solution?

When asked if the high-rise project might be a drastic emergency procedure for an area that just needs some preventative care, Miller disagrees.

“I think if some of the newer uses that have come to the area continue, then we’re close to resuscitating a dying patient.”

A drive through the vicinity confirms that there is room for improvement, with some vacant spaces and eyesores along parts of Garland Road. But in addition to the old and dilapidated strip centers, there are some new developments, including the Reserve, a mid-rise multi-family apartment building, and a refurbished strip shopping center next door to the proposed site of the high-rise. Casa Linda Plaza may not be the destination it once was, but it is still a thriving shopping center serving thousands of residents daily.

Even proponents of the high-rise admit that 500 new residents will not, by themselves, have a huge economic impact on surrounding businesses. Jim Brown, chief operating officer of Doctor’s Hospital, said he supports the project, but the benefit to local businesses depends on the type of customer the project attracts.

“A project of that magnitude could serve as an economic engine. We benefit from new residents,” Brown says. “What the developer foresees is a mix of old and new residents moving in. In that case, the impact won’t be as great.”

City Plan Commissioner Bill “Bulldog” Cunningham also doubts that a single project could spark an economic boom along Garland Road.

“Five hundred people probably is not enough to affect the surrounding economy drastically, but it would augment it. I don’t see any reason for an avalanche of new retail going in to substantiate the existence of 500 people coming in. There may be a few higher-end restaurants going in.”

Local restaurateur and president of the White Rock Lake Foundation, Jeannie Terilli, says one major barrier preventing some businesses from coming to the area is the fact that Garland Road is dry from near East Grand beyond Buckner.

“Restaurants and developers want to be in wet areas,” Terilli says. “Being in a dry area makes everything harder.”

And many residents believe the problem with Casa Linda Plaza is not that there isn’t a large- or affluent-enough market to sustain it, but that the Casa Linda Theater still sits unoccupied, blighting the shopping center with its outdated marquee and deteriorating façade.

Theatre Brothers Ltd. bought the theater a year ago, and its owners insist that an announcement about new tenants could be coming in the next 30 to 60 days. Of course, they’ve been saying that ever since they bought the space, which could raise further concerns about the economic viability of the area.

Still, the larger questions remain. Will the proposed high-rise attract more developers to the area? If so, will that set a precedent for more high-rise buildings?

Miller, Cunningham and Brown believe such a project will be the start of more high-end developments along Garland Road. They also admit they can’t guarantee it. And while Miller takes great pains to explain why it’s unlikely that a glut of high-rises will surround White Rock Lake, anything is possible when, or if, more developers start moving in.

As with any business venture, Miller can’t even guarantee that the high-rise itself will be successful.

“This is a $50 million bet,” he says. “We’ll hedge the bet with pre-sales of units.”

The Height

While the direct and indirect economic benefits to the community are debatable, one thing is certain: Once a 25-story high-rise is built at White Rock Lake, even if it’s the only one, the lake view will be changed forever.

It may be nothing more than a tiny man-made reservoir on the eastern edge of Dallas, but in a city mostly devoid of natural beauty, it may as well be Lake Superior. So it’s no surprise that surrounding homeowners are fiercely protective of what has become, for thousands, a peaceful refuge from the congested reality of city living.

Little Forest Hills resident Kristin Laminack says it’s the one place she can go to temporarily forget about the rat race.

“I like walking around the lake and forgetting I’m in Dallas and looking off in the distance and seeing downtown and thinking, oh yeah, I’m in the city.”

As another neighborhood resident, Jennifer Holmes, put it: “I don’t want to see a big obelisk as I’m walking around White Rock Lake.”

Complaints such as these, of course, are part of what’s driving the opposition to Miller’s plans. If he puts one high-rise near the lake, residents wonder, how long before the next one pops up?

In an effort to allay fears that his project will open the floodgates to more high-rise developments, Miller says high-rises are unlikely to the west of the lake because of the money and influence of homeowners there, to the south of his site because of the 75-acre Dallas Arboretum, and to the north because of the “newish” developments he speculates are unlikely to be available to high-rise developers for the foreseeable future.

Adding to the confusion, Cunningham agrees that there’s not much land around White Rock Lake and Casa Linda Plaza that might become available for development of high rises, but also notes that it’s just a matter of time before high-rises become the norm in all parts of Dallas out of necessity, and White Rock Lake would be a prime location.

“We can only build up. We’re not making any more land,” Cunningham says. “And there are not very many opportunities to build with a view of water.”

The proposed height of Miller’s structure is, of course, where he’ll face the toughest resistance. It’s also the weakest point in the sales pitch. He says he wants input from the community, yet he has been initially unwilling to discuss any changes to the structure other than architectural and stylistic elements.

“We come here with a vision, and want the community to take ownership of the project,” he told the crowd at the Little Forest Hills meeting.

In an interview a few days later, he had refined that statement to better fit the reality of the situation: “Tuesday was our first town hall meeting, and we will have as many as we need to get the community to buy into our vision.”

He may discover that no number of town hall meetings will accomplish that feat, but at the moment there’s no indication he’s willing to negotiate the height of the project. As a businessman, he needs to sell a certain number of units to make the project profitable. Not surprisingly, he won’t reveal that number. Instead, he maintains that it’s not the profit motive that is driving the structure so high, but his sincere desire to affect the most positive change in the community.

“We have always believed it’s not going to happen again,” he says. “Let’s make it have the most impact possible.”

But Miller admits this project isn’t the only opportunity for redevelopment and revitalization around White Rock Lake — just the only current opportunity for this type of high-density, high-rise project, which suggests that cramming the most possible units into a two-acre plot of land is at least as important as the potential benefits to the community.

Down to Earth

Of course, all of this posturing on both sides may be premature and beside the point.

Miller’s proposal for a 25-story building could be nothing more than a negotiating element meant to make anything shorter seem more palatable to neighbors. Indeed, early meetings with area business owners featured a 10-story rendering of the project.

Could 10 be the magic number? Miller says no, that the rendering was really just a rushed material study to incorporate architectural and stylistic changes suggested in a previous meeting.

District 9 Councilman Gary Griffith says he won’t know what the developers are really asking for until they formally apply for a zoning change.

“My first instinct is that 25 stories is too tall,” Griffith says.

On the other hand, maybe Cunningham’s position that high-rises are inevitable in a city that is “not making any more land” is worth considering. If it really is just a matter of time before White Rock Lake resembles Central Park, it might not be a bad idea to start with a developer who at least has a connection to the area and is willing to listen, if only to stylistic suggestions.

As Miller says: “I’ve seen what happens when nothing happens.”

Now he just has to bridge the gap between nothing and 25 stories.