Photo by Danny Fulgencio

Seniors in parts of East Dallas are facing a mounting problem. As they age and lose their ability to drive, they are isolated because they live in transportation deserts, where a resident has to walk more than a quarter-mile to get to the nearest rail or bus line. The East Dallas Seniors Coalition has been working with Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) and state representative Eric Johnson to address the issue, but they worry that the problems that have plagued the system will continue.

John and Ellen Childress moved back to Dallas in 2005 from their farm near Gun Barrel City because Ellen lost her ability to drive and wanted to move to a city with better public transportation. They bought a quaint brick house behind Bishop Lynch High School with a bus stop on the corner, but the week they moved in, the bus stop was removed. They have been advocating for their neighborhood ever since.

The coalition of seniors formed when members of many of the crime watch groups that run along Ferguson Road organized and began to advocate for the elderly citizens in the neighborhood who wish to age in place. Transportation was a major concern. Many of the elderly folks in the neighborhood could no longer drive but lived too far from a bus stop to walk the necessary distance. Since many are on a fixed budget, finding affordable ways to get to doctor’s appointments, the grocery store and social outings became a priority.

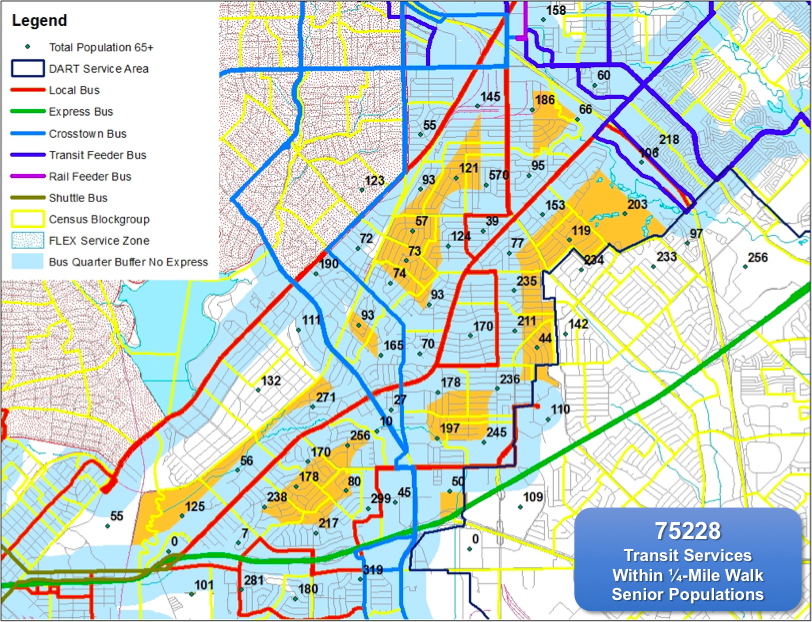

DART’s own data confirmed their worries. They conducted a study among older East Dallas residents about their transportation needs and found numerous pockets where public transportation was out of reach. The yellow shapes below are the areas where the nearest public transportation is more than a quarter mile away.

Image courtesy of DART

The seniors contacted state representative Eric Johnson, who helped coordinate a meeting with DART officials to try and find a solution. This isn’t a state issue per se, but Johnson was happy to connect his constituents to DART’s powers-that-be. “We have the relationships we need to cut through the red tape to talk to the person you need to solve your problem,” he says of state representatives. “We throw ourselves into it and try to be helpful.”

The seniors highlighted a program called DART On-Call, which brings Dallas residents who live in certain areas to rail stations during peak hours. In between the two rush hours, residents can call DART and be picked up within the hour for a flat $5 daily fee. For the seniors who don’t live near a rail line, this is much cheaper than other transportation options such as Uber or a taxi.

DART On-Call only serves limited areas in Dallas such as the Park Cities, Lake Highlands, Lakewood and Preston Hollow. Some members of the East Dallas Senior Coalition question why this affordable service is limited to wealthier areas of Dallas, while working class areas in transportation deserts don’t have the option. Ironically, the DART On-Call service hub sits in the area near Ferguson Road, meaning the vehicles may pass through their neighborhood in order to get to other service areas.

“Why don’t you make the simple fix for this part of the neighborhood?” wonders Desi Tanner of the coalition. “We need the same thing here. Why couldn’t we have the same services?”

DART officials are proposing an alternate solution that has been successful in Plano, where DART enters a deal with a taxi company to provide discounted transportation. In this program, Plano citizens who are over 65 can load $100 worth of transportation dollars onto a card for $25 each month, allowing them to travel for one-fourth of the cost up to $100 a month. Users can pay for the value card via check or online. The program is funded by both DART and a grant from the North Central Texas Council of Governments.

This program could help alleviate the transportation issues for seniors in transportation deserts, but some in the East Dallas Seniors Coalition wonder why DART can’t extend the on-call service that already exists so close to their neighborhood. They also think the voucher program will be more difficult because it requires users to register online, while the on-call service is booked over telephone, which is easier for many elderly users.

DART hopes to roll out the voucher program between July and September 30, but it depends on when the grant is available. DART administrators hope to communicate to seniors about the new program through churches and neighborhood groups, as many aren’t fluent with the internet and social media. While the East Dallas seniors think the voucher program is a good one, they are worried the grant might be delayed and are still pushing for a more immediate solution, such as expanding on-call.

“Something five to 10 years down the line doesn’t feed the bulldog,” John Childress says. “We want solutions now. It is beginning to get pretty desperate when you think about it.”

Ellen Childress is president of the coalition, and feels that her working class neighborhood, which includes Truett Elementary where 37 languages are spoken, has been neglected by the city in terms of services. “It’s like they carved us out of the City of Dallas and dropped us off the side of a cliff.”