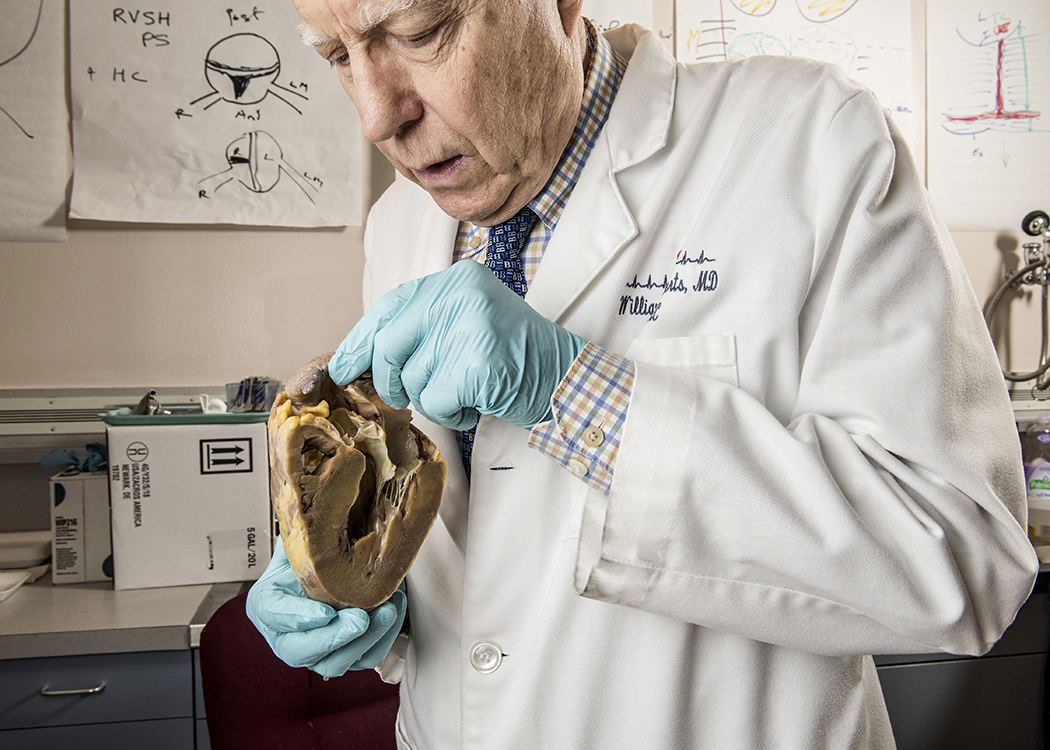

Dr. William Roberts meets with transplant patients and teaches them about their former heart. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

After a trip to the Philippines in 1996, Brad Rountree went to the cardiologist with chest pain and was told his heart may have been attacked by a virus. Nearly 20 years later, he held his heart through Baylor Hospital’s Heart to Heart program.

In 2015, he was diagnosed with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, a disease of the heart muscle that causes the ventricle to stretch and thin, losing the ability to pump blood effectively.

“My heart had a shelf life,” Rountree says.

He needed a heart transplant and was put on the list. Three days later, he had a new heart.

Rountree knows how fortunate he is to have received a transplant which is both expensive and rare. “They said I had 24 hours to live,” he says. “But when I opened my eyes, I had blood coursing through every vessel in my body. I felt like I was 25 years old. ‘Is this going to go away?’ I thought. ‘Nope!’ ”

While overjoyed, he knew that receiving a transplant meant someone else had died. His heart came from a 24-year-old man who died from brain tumors.

Rountree wrote a letter to the man’s family, describing his children, his job as a pastor at New Liberty Baptist Church in Garland and his role singing in the Dallas Symphony Chorus. “I wanted to thank them for being willing to give life,” he says.

Baylor’s Heart to Heart program offered another opportunity for emotional closure. The idea started when a former heart transplant patient approached Dr. William Roberts, Executive Director of Baylor Heart and Vascular Institute. “I understand, Dr. Roberts, that you have my heart,” the patient said.

Roberts invited the patient to the weekly cardiac pathology conference, where he could see his ticker. A tradition was born.

Rountree, too, listened to Roberts talk about his heart. Then he held it in his hands. “It was educational and put me at ease,” Rountree says. “He wanted to know what my story was and what I thought.”

The heart looks more like a raw chicken breast than a pulsing blood pumper, but for many it provides a closure to a trying process and allows them to say goodbye to an essential part of themselves. “This is the heart that my mom and dad gave me,” Rountree says.

As a result, Rountree now volunteers at Baylor, talking with recent and future heart transplant patients.

Roberts is 85 years old and still busy as ever, penning articles, cracking jokes, running the institute while spreading the gospel of a pescatarian diet.

“It ends one very traumatic phase of life,” Roberts says. “It opens the door for this new normal phase, with vigor, enthusiasm and happiness returning. Patients have an added responsibility to take care of this new heart.”

DID YOU KNOW? Baylor Hospital surgeons have performed 870 heart transplants since 1960 and complete about 60 per year. More than 100 patients have taken part in the Heart to Heart program.

Slicing a cross section of the heart allows former transplant patients to see how their organ was suffering. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)