What it means to be part of The Greatest Generation

We wait alongside them in the grocery checkout line and hurry past them on the street. They are members of our churches and grandparents to our children, but how often do we pause to ponder the content of their lives?

As teenagers and 20-somethings, they traveled to distant countries, knowing they might die there, and returned to lives forever altered by their experiences. They risked their lives, left jobs, and cast passions and aspirations aside until their missions were fulfilled.

Indeed, all who served in World War II — in battle or supporting roles — deserve unyielding gratitude, but as each Veterans Day passes, the time for thanks dwindles. We can still shake their hands and hear their stories, but for how much longer?

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ewGMwiZrFBw[/youtube]According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the ranks of World War II vets are shrinking by about 1,200 a day nationwide.

A few of those who have retired in the East Dallas area take time to recall, for those of us who weren’t there, an era that shaped the world.

If you run into one of them today, it might be the right time to say “thank you”.

“We got on the beach at 9:30, and the seawall had not been blown as planned.” — Lynn Guilloud

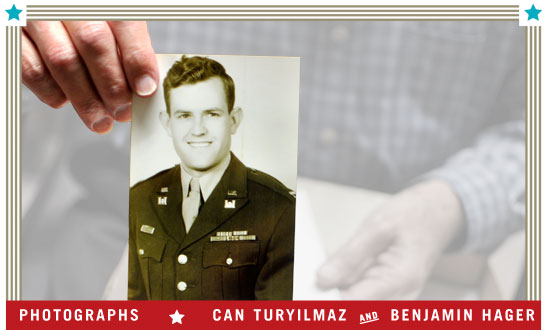

Lynn Guilloud was a farm boy from North Texas, so poor that when his dad dropped him off for his first semester at Texas A&M University in 1938, he had $68 in his pocket and no place to lay his head.

But he went on to graduate with a mechanical engineering degree in 1942. And he became a company commander in the U.S. Army, leading three platoons onto the beach at Normandy.

At 89, Guilloud lives in the M Streets with his second wife, Mary, whom he married nine years ago.

Guilloud says he hasn’t always been forthcoming with war stories, but now he talks freely and at length about his World War II experiences.

When he turns to memories of men 66 years dead, his voice cracks, and he pounds a fist three times, hard, against his thigh. He inhales deeply and pauses for a moment, but he doesn’t cry.

“This is ancient history to most people,” he says. “Don’t romanticize it. Just tell the facts.”

On the morning of June 6, 1944, Allied Forces totaling some 160,000 men landed on the beach at Normandy. Guilloud was 23 years old, and he was in charge of about 100 of them.

“Allied planes were thick,” he says. “The sky was almost black with them.”

From his boat, a Landing Craft Tank, he could see smoke rising from the beach. Their vehicles had been meticulously waterproofed, and they pulled them off in about four feet of water.

“We got on the beach at 9:30, about three hours after the initial landing, and the seawall had not been blown as planned,” he says.

As it turned out, they had landed one kilometer off course, which caused much confusion. They got enough men together to lift a Jeep and an anti-tank gun over the seawall before they found the blown gap farther down the beach.

Guilloud’s engineering company went to work right away putting in a bridge. When it was finished, he flagged down someone he assumed to be a military policeman to tell him the bridge was in, and found it was Theodore Roosevelt, son of the former president.

Once their work was finished, Guilloud’s company retreated to the bivouac area. By that time, they had been mostly without sleep for five days.

“Man, what a mess,” he says.

Vehicles were all over the beach. Everyone was confused. The dead were everywhere.

The company bridged the Douve River to connect the beaches, and more than 6,000 vehicles crossed there.

They followed the infantry through the battle-ruined town of St. Lo.

“It was a terrible sight,” Guilloud says. “The stench was awful. There were dead people, dead animals. Nothing but rubble.”

As part of Gen. Patton’s army, they moved forward, constantly, to put in another bridge.

Once, his company was to build a bridge at a town called Gavisse, and it was raining. The river flooded its banks, so they built the bridge sections in town before assembling them at the river. They got the bridge in, but the rain persisted, and the river kept rising.

As vehicles crossed, the bridge pulled loose, ripping great trees out of the ground. Several men drowned inside their vehicles after the bridge flipped.

This is where Guilloud’s story pauses.

In 1994, he took his whole family to France. In his office, there is a picture of Guilloud and his grandson standing beside that river where, eventually, the bridge held. Gen. Patton himself would cross it the same day it went in.

The rest of the war met Guilloud with freezing cold, hunger and terrifying brushes with death that haunt him to this day, he says.

As our interview winds down, Mary Guilloud enters the office to ask if we’d like some iced tea.

“Did we still win?” she teases her husband.

Her daughters were in Sunday school classes that Lynn Guilloud taught many years before their respective spouses passed away.

Guilloud was an engineer for Ford Motor Co., Frito Lay and Yellow Freight. He recently had a pacemaker installed. And he still has lots of stories to tell.

“We were somehow going to get past the guards and escape Switzerland because the Air Force needed pilots.” — Bob Lucas

Bob Lucas was a B-24 pilot, and he flew 13 bombing missions over Germany in 1943 and ’44.

On the 14th one, he got really lucky.

His target was Friederickson, a town in southern Germany.

“We had to fly across the target twice because another bomber group was right under us,” he says. “So we had to make a wide circle, which made us more vulnerable. I thought we were going to be killed instantly when we made a second run.”

Six planes were shot down over that target, including the one Lucas was flying. The plane lost fuel and hydraulics, so he couldn’t make it back to England.

“Our orders were, if anything went wrong, to try to get to Switzerland,” he says.

Switzerland was neutral during the war. If Axis or Allied planes went down there, the pilot and crew would be interned until the end of the war.

So they made a course for Switzerland.

The landing gear was gone, so they were facing a crash landing. They came down in three or four feet of snow, he says, and that’s the lucky part.

“It was like landing on water. We just glided right through,” he says.

If not for the snow, the plane would have broken apart and caught fire from friction when it hit the ground, he says.

The Swiss Army showed up and took them to a town called Davos Platz, and they stayed in an old hotel there. They were allowed to walk around the town, but they couldn’t leave, and there were guards at both ends of town to make sure they didn’t.

They knew that if they were caught trying to escape, they would be put in prison until the end of the war.

Lucas had been in Switzerland six months when the Swiss commanding general came in and called a meeting with the interned pilots.

“He said we were somehow going to get past the guards and escape Switzerland because the Air Force needed pilots,” Lucas says. “He said, ‘We can’t tell you how, but you’ve got to get out.’ ”

They were given train tickets to Geneva and about $20.

Lucas found some women’s clothing that fit him: a dress, shoes, a big hat and a bag, into which he put his clothes. He blended with the crowd, got past the Swiss guards and made it onto the train to Geneva.

Once he was in Geneva, he had instructions to get into the back of a truck with a covered bed. The truck took him to the home of a wealthy American who lived in Geneva, and about eight men stayed there for several days.

A six-foot-tall chain-link fence with three rows of barbed wire at the top marked the border between Switzerland and France.

They received word that the French guard at a nearby crossing had been paid off and would let them through. So they set out at midnight on a very black night.

Lucas was walking with “another country boy” and he had a hunch that something might be amiss with the plan.

They dropped back from the group, “to see if everything was kosher,” Lucas says. “Otherwise, we’re all going to the penitentiary.”

They were about 100 feet back, but the night was so dark, they couldn’t be seen. And they heard a lot of arguing and yelling from the gate.

“We walked down that fence a ways, and we climbed that darn fence,” he says.

They had escaped, and they slept during the day and walked at night toward Lyon.

Eventually, an Army sergeant in a Jeep picked them up and took them to the base at Lyon.

Lucas was given a 30-day pass, and the Army put him up in a hotel in London, where he says he partied every night.

For the rest of the war, he flew supplies missions. But he’ll never forget the day he returned to the United States.

“One of the prettiest things I’ve ever seen was the Statue of Liberty and a big American flag,” he says. “I thought, ‘Thank God. Thank God for America.’ ”

Lucas is 90, and he lives in East Dallas. He’s been retired from IBM since 1965. He runs a small real estate business, and he loves a good joke as much as a good cocktail.

“When I got in that B-36 outfit, I memorized that plane like nobody’s business.” — Orville Rogers

Orville Rogers excuses himself from the formal living room with the pretty white sofa his wife bought 60 years ago, and he brings out a model of the B-36.

He says it was the world’s biggest plane when he was flying it.

He loves this plane.

When Rogers was a little boy growing up in Texas and Oklahoma, he prayed to become a pilot. His father had left his mother, older sister and him when he was 6. But he didn’t care.

He grew up on his mother’s parents’ farm in Oklahoma during the Great Depression, but he didn’t know there was a depression.

He had a collie and an old horse he rode bareback, and his only dread was picking cotton.

He graduated from the University of Oklahoma and joined the Army Air Corps, which later became the U.S. Air Force, five weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Flight school was a dream come true, he says, the beginning of a prayer answered.

“Everybody’s gung-ho at that age,” he says. “I thought I wanted to be in combat.”

He was in B-17 training when the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

“The atom bomb probably saved my life,” he says.

Rogers served as a flight instructor throughout World War II and the Korean War, and he once dropped a dummy bomb during a practice run, but he never saw combat.

The B-36 was the “main plane” during the Cold War, when Rogers had an “assigned target” should war break out.

“It could fly higher than any fighter,” he says.

It could stay in the air for 30 hours or longer, and it could fly above 50,000 feet.

“I’m sure the Russians knew that,” he says. “To my dying day, I will think that was the main deterrent of Russia during the Cold War.”

The B-36 had 10 engines, eighteen 20-millimeter cannons and technologies that Rogers explains with gusto.

“When I got in that B-36 outfit, I memorized that plane like nobody’s business,” he says. “I ate that airplane up.”

Rogers is 92. He lives near White Rock Lake, and he started running when he was 50. He holds United States and world records for his age group in the mile, which he runs in under 10 minutes.

He has 12 grandchildren from his kids, Bill, Rick and Susan. His oldest son, Orville Rogers Jr., was a pilot in the Marines who was killed in Vietnam in 1970.

He flew for Braniff Airlines and retired well before the company failed.

“I didn’t like military life,” he says. “I enjoyed the airline flying more than you can imagine.”

After retirement, he and his wife flew missions to Africa and Asia, providing supplies and transportation for Baptist missionaries.

“God has blessed me,” he says. “And I think it’s because I devoted my life to him.”

“I worked hard, learned a lot, and saw the world.” — Howard Riggs

In 1943, when the military was drafting his high school classmates, Howard Riggs joined the U.S. Navy — thankfully, he says, he was allowed to finish his senior year before reporting for active duty. Today, after living 40 years in the White Rock Hills area, he lives with his wife, Glenn Eva Riggs, at C.C. Young retirement community in the White Rock Lake area.

Straight and tall, wearing a neatly pressed polo-style shirt, Riggs walks into the cafeteria and offers a firm handshake. He clutches an antique brown leather-bound photo album. Inside the book are images of smiling 20-somethings in uniform, Chinese children in a shipyard, beautiful beaches, vast Naval ships and striking examples of Asian architecture, including Bejing’s Forbidden City.

In China, Riggs supervised a coal storage plant, and although the warehouse in his area once burned to the ground in an impressive fire, Riggs says destruction and fear were not much a part of his World War II experience. Though it interrupted his education and career, Riggs says he was grateful for the opportunity to travel and to learn leadership skills and decorum.

“I did what I had to do,” he says, “worked hard, learned a lot, saw the world, and had fun.”

He was recalled for the Korean War in 1952. By then, he had graduated from college at Washington University, just married Glenn Eva, and was climbing his way up the corporate ladder at Safeway, where he eventually worked 40 years in advertising.

He says, bluntly, about his Korean call to duty: “I didn’t like that, but I just had to do it.” Riggs spent 24 months loading ships in the Philippines before finally returning home.

“When I returned to work, I found I’d been replaced by a guy I’d hired,” he says with benign irritation.

He remained in the reserves, and retired from the Navy as a commander in 1962 — in the ensuing years, he and his wife had two children, five grandchildren and four great grandchildren.

In October, Riggs traveled to Washington, D.C., courtesy of the Honor Flight program, which allows WWII vets to see the WWII memorial.

Read about the Honor Flight of Dallas, an organization that aims to give veterans an all-expense paid, overnight tour to Washington, D.C., to see the National WWII Memorial.