A video captured by a spectator of a car sliding at a blocked intersection by U.S. Highway 75 while a passenger hangs out the side window holding a flag.

YOU CAN HEAR IT FROM MILES AWAY.

Engines roaring, tires screeching and spewing clouds of smoke, spectators yelling and cheering. Sometimes fireworks and gunshots ring out when the crowd gets especially excited.

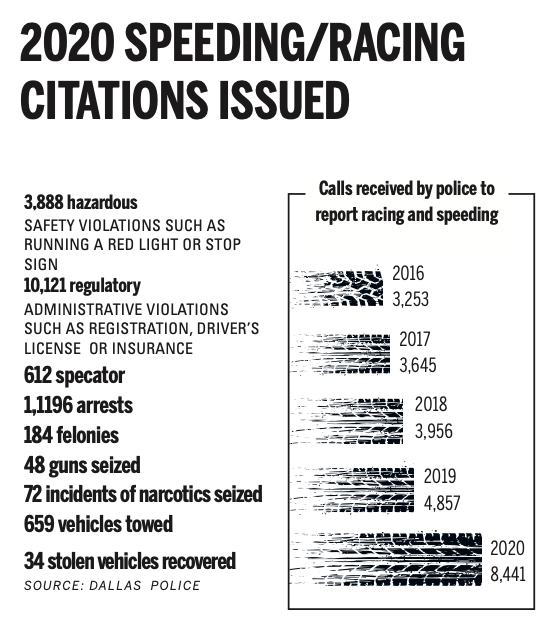

Reports of street racing from the Dallas Police Department shot up to 8,441 in 2020, from 4,867 the previous year. 911 calls related to speeding and racing have increased every year since 2016. Metrics from the first part of 2021 show no signs of decreasing.

“My No. 1 issue by far, and not even close to anything else, is street racing and police response to it,” District 14 City Councilman David Blewett says in a recent meeting. “I’ve been getting constituent complaints for upward of 12 months now.”

Street racing and car stunts are by no means new phenomena, but last year, intersection takeovers, excessive speeding and extremely loud vehicles started to infiltrate downtown. People noticed the problem, and DPD patrols increased. Lane reductions at key intersections and temporary stop signs were implemented to calm traffic.

“Curbing street racing in the city became a priority, and it worked,” Councilman Chad West says. “But, since it worked, it got pushed to the neighborhoods.”

DPD’s limited resources mean officers find it hard to keep up. Blewett says on any given weekend, there could be 1,000-2,000 racers in the city. Dallas has about 1,600 traffic signals, so there are plenty of potential takeover sites.

Also hampering DPD is a strict policy on high-speed pursuit, revised in 2011 after it was determined that high-speed chases, often over misdemeanor offenses, result in increased injuries and deaths. Now, officers only engage in pursuit when they can identify a threat of physical force or violence.

And, like almost every other aspect of life, COVID-19 has played a part.

“The pandemic has greatly exacerbated this,” Blewett says. “It’s mostly younger people who are stuck at home, some not able to go to work or school. They’re looking for fun and action and not having many options.”

At times, crashes related to racing and drifting in intersections have resulted in property damage, injury and even death for participants and innocent bystanders. An off-duty police officer died in late 2019 after a racing-related crash near White Rock Lake.

“It was actually quite terrifying because some cars were getting a little too close for comfort. One wrong move and you’re done.”

Incidents have residents stirred up. In April, neighbor Jeff Auvenshine was on his way home from grocery shopping when he found himself with a front-seat view of a takeover at the Skillman and Live Oak intersection. Within seconds, cars were spinning out in front of him. He posted videos on Twitter.

“It was actually quite terrifying because some cars were getting a little too close for comfort. One wrong move and you’re done,” he says. “Anyone on the side of the road could have been hit or one of us in one of the cars.”

As sirens got closer, spectators jumped into moving cars through the windows, he says.

“It was quite the scene.”

This foolishness just happened in Dallas at Live Oak & Skillman. Blocking all traffic. Part 1. @NBCDFW @FOX4 @wfaa pic.twitter.com/9pR1WNkCAw

— Jeff Auvenshine (@jeffauvenshine) April 27, 2020

Racing vs. takeovers

Labeling it all as “street racing” is oversimplification.

“There’s actual street racing, and then there’s the parking lot takeovers and highway-takeover group,” says a professional hot rod shop manager who did not want his name used.

He says he was into cars when he was a kid, but he first became involved with street racing when he was a teenager.

“I used to go out with my friend’s dad,” he says. “We’d go out to the track, and then after, go out to the street and try to find street races.”

Street races happened off the main roads and usually late at night, the manager says. He got serious about it when he turned 16 and got his own car.

“That’s what I would spend my money on,” he says. “I’ve done every aspect of it: the paint, chassis, motors, interior.”

To him, street racing is nothing like the intersection takeovers.

“That’s more of a gathering of people with cars, and those are the ones that end up giving everyone a bad name,” he says. “Those are the ones that are out of control.”

The takeovers, also known as slideshows, involve cars blocking an intersection or parking lot. They attract people mostly under the age of 25. Drivers swing cars around in circles — burning rubber — often coming close to spectators. These events tend to draw larger crowds.

Spectators cluster together while a car spins around them at high speed during a takeover at Noel and Spring Valley.

A Lake Highlands resident who sometimes goes to takeovers tells a different story.

“They don’t let just anyone go in the pit, the middle of the group, where drivers do doughnuts,” says the neighbor, who didn’t want to be identified. “It’s only extremely good drivers. They go and practice all the time.”

He says he stumbled across his first takeover by accident, when he was out late one night.

“I was curious about it, so I looked on social media, and I saw some accounts. You have to message proof that you saw street racing or something that proves you’re not gonna rat them out to get in some groups,” he says. “I’m not a car guy myself. I just get bored and want to go watch it.”

Takeovers are typically organized on social media. Private Instagram accounts post scheduled events, and people can communicate through direct messaging which cars will block off which streets and who will be posted where to watch for police.

A car throws out a cloud of smoke while spinning out. Street racing is currently a priority two call, which means a 12-minute response time for officers to get to the scene.

“Street racing people are smart. They’re innovative, and they’ve adapted around our tactics,” Blewett says. “[Police] will try to get there before they block off the highway. All you can do is keep them moving rather than allow them to take over the intersection because they haven’t broken a law yet.”

Blewett doesn’t see law enforcement as the only method of curtailing reckless driving.

“There’s a PR war that we need to be involved in because right now, the kids who are doing this, they just think it’s fun. They don’t think it’s dangerous,” he says.

“My solution to anything is a carrot and a stick. We can keep using sticks and raising the pain, but at some point … is there a carrot to incentivize them to use this energy and do it in a safe way?”

DPD reporting doesn’t differentiate between street racing and sliding, so it’s hard to say which is more prevalent or more dangerous.

Taken together, though, reckless driving has taken over Dallas. In a recent public safety town hall, Jon Fortune, assistant city manager for public safety, says that in 2020, DPD issued more than 4,000 hazardous citations, 10,000 regular citations and 600 spectator citations. Officers have made more than 1,200 arrests related to reckless driving. Police towed nearly 700 vehicles and recovered 34 stolen vehicles during that period.

In May 2020, City Council passed an ordinance to impound cars and ticket spectators. Even though there was an uptick in citations, there was no noticeable decrease in behavior, Councilwoman Jennifer Staubach Gates says.

With DPD’s policy on pursuit, drivers typically aren’t caught. When they are, they face relatively low fines. Their vehicles are impounded, but the perpetrators have to be convicted for their cars to be seized, and it can take multiple convictions for that to happen.

Some at Dallas City Hall want the Texas Legislature to change laws to make it easier to seize cars and punish offenders.

“If we were seizing more cars, these guys would think it’s not worth it because that’s a pretty heavy penalty,” Blewett says. “However, my solution to anything is a carrot and a stick. We can keep using sticks and raising the pain, but at some point … is there a carrot to incentivize them to use this energy and do it in a safe way?”

Carrots and sticks

That’s the view shared by many in the car scene. Ricardo Anderson sent an email to Blewett last year identifying himself as a swinger and asking for help in creating a “special spot” to get swingers off the streets.

“Trust me, we getting tired of running from y’all,” he wrote. “Us swingers want to be safe as well, left alone in peace. We previously had a secret spot that DPD found and decided to raid a few months back. We just want our spot back.”

There’s a petition on Change.org from TSNLS Dallas, an Instagram account that posts videos of street racing, requesting “a legal lot to slide so NOBODY gets hurt.” The petition had 1,501 signatures as of late February.

In theory, designating a spot where people can race and slide without endangering residents sounds promising, but endorsing a space like that is tricky. There isn’t much City Council interest in cooperating with street racers and sliders.

“It’s problematic for us to bless this because we’re going to be liable in case anything bad happens,” Blewett says.

Even if designating a spot helps the problem, there’s no immediate relief.

One strategy that has seen some success was implemented on Lower Greenville, where the street was reduced from four lanes to two. The average speed on Greenville Avenue dropped by about 15 mph, and all crimes fell by 80 percent, according to the Project for Public Spaces website.

Road dieting, another term for lane reduction, was also temporarily implemented in Oak Cliff along Hampton Road, a busy thoroughfare that sees excessive speeding and intersection takeovers. Using traffic cones, the six-lane road was reduced to four lanes on the weekends, which pushed traffic together and effectively slowed drivers. With the road diet, Hampton saw about a 75 percent decrease in 911 calls related to street blockage and a 65 percent decrease in calls related to street racing.

“I am actively looking for creative solutions … I’m sure it’s out there, and I’m open to it.”

Similar lane reduction with traffic cones is planned for the Garland-Gaston-Grand intersection sometime this spring.

“We’re trying, and we’re experimenting in different parts of the city to see which [strategy] works where,” says Ghassan Khankarli, assistant director of the transportation department, in a recent meeting about racing on Skillman Street. “One treatment in one area works, but it might not work in another area. Or we might need a hybrid. We’re trying to come up with the best solutions.”

Meanwhile, DPD is exploring the expansion of intel and surveillance techniques, and the City is conducting traffic studies to diagnose problem areas. The Neighborhood Traffic Management Plan, Traffic Management Toolkit and the Connect Dallas Strategic Mobility Plan aim to comprehensively tackle Dallas street safety.

“I am actively looking for creative solutions,” Blewett says. “Whether it’s a solution coming from DPD, a reporter or other citizens. I’m sure it’s out there, and I’m open to it.”

You can report street racing on the City’s 911 iWatch Dallas app or by calling 911.