Pampel family. Photography by Megan Moates.

One day at the Ashford Rise School, director Maude Pampel received a visit from her son, Sam. His teacher wanted him to show Maude a bump on his face.

Maude and Tony, Sam’s dad, took their son to the doctor, who prescribed antibiotics. Because the bump was around Sam’s neck and ear, they hoped it was a swollen lymph node.

When the antibiotics didn’t have any effect, doctors thought Sam might have a bad ear infection, so he was given stronger medication.

“It’s kind of one of those things. You hope to treat it. It’s going to go away,” Maude says. “But we took him back, and then we took him back again.”

That bump was the start of a four-year health crisis for this neighborhood family that led them across four cities in two states to find doctors and hospitals offering specialized, and usually invasive, treatments.

Through it all, they were met with an outpouring of support from nonprofits, neighbors, strangers, friends and family. Whether it was delivering meals, mowing the lawn or expressing verbal and emotional support, neighbors never stopped caring.

Weeks after the teacher first spotted the bump on Sam’s face, they were back at the doctor’s office. The doctor prescribed a different kind of antibiotic and said she would call other physicians to see if they had any ideas.

Maude was in line at Walgreens when the doctor called, instructing her not to give Sam the prescription. The doctor wanted Sam to see an ear-nose-throat specialist the next day. If Sam took the medication, it could have masked symptoms.

Tony drove Sam to the appointment. The doctor asked Sam to lie down for the examination. He was surprised, Tony says, because he pulled a glob of dried blood out of Sam’s ear.

“That’s not supposed to be there,” the doctor said.

He was looking at Sam’s ear using a tool connected to a monitor.

“Mr. Pampel, I need you to come over and look at this,” the doctor said.

On the screen, Tony saw a picture of something hanging down in Sam’s ear canal: a tumor.

Over those weeks, the family had been clinging to hope. Slowly, with each new piece of information, hope was being taken away. Maybe it was just a swollen lymph node. It wasn’t. Maybe it was a benign tumor. It wasn’t.

They took Sam to the hospital’s oncology floor, to a nice room with big couches. That’s where doctors explained the situation. They didn’t yet know the cancer was neuroblastoma, Maude says, but something had to be done. Treatments had to begin.

With the initial “intermediate risk” diagnosis, Sam started chemotherapy and other treatments at Medical City Children’s Hospital.

But while he was undergoing therapy, Sam relapsed and was given a “high risk” diagnosis. This time, doctors found a 2-centimeter mass between his brain and skull. They were clued on to something being there when Sam woke up one day, screaming in pain because of a severe headache.

Tony drove Sam to Las Colinas Proton Center, where every weekday for four weeks, Sam was sedated and given radiation treatment. And when the cancer was small enough, a surgical procedure removed it.

“Imagine a 4-year-old at this point, trying to run around with a surgical drain out of his head,” Tony says. “We did chemotherapy again — harsher, bigger drugs, some of the platinum-based drugs that at that point actually knocked out his hearing in one of his ears.”

Photography courtesy of Maude Pampel.

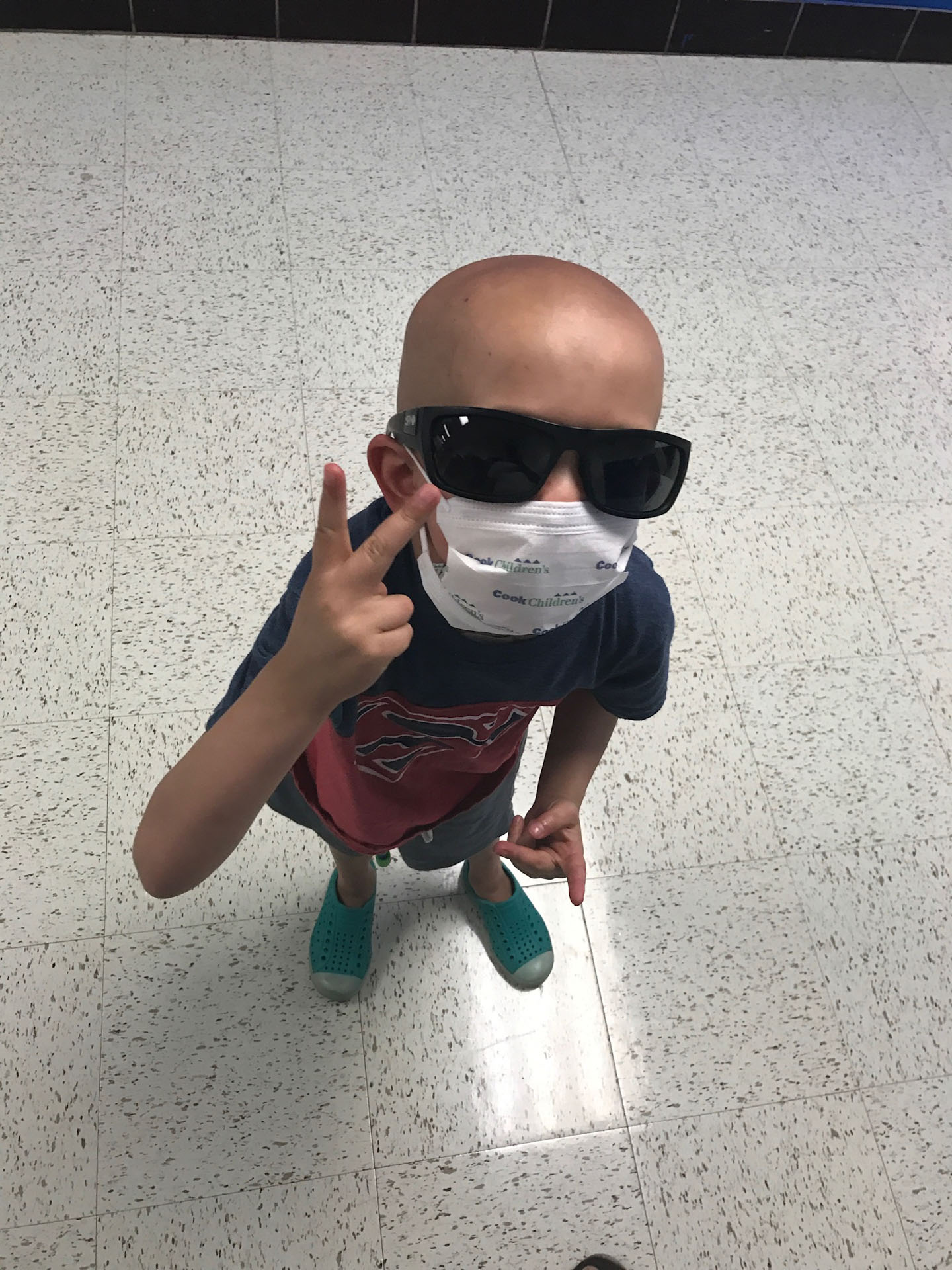

Then Sam had an autonomous stem-cell transplant in a completely sterile environment, what Tony calls a “supermax for germs,” at Cook Children’s Hospital in Fort Worth. An apheresis catheter — or a “soda straw,” as the Pampels named it — was inserted into Sam’s neck, allowing doctors to collect blood and harvest stem cells. Once enough cells were gathered, Sam was given a lethal dose of chemotherapy, enough to kill all the red blood cells in his body.

The only thing keeping him from dying was the stem cells, which kickstarted bone marrow production after they were injected back into his body. Without bone marrow, Sam had no immune system.

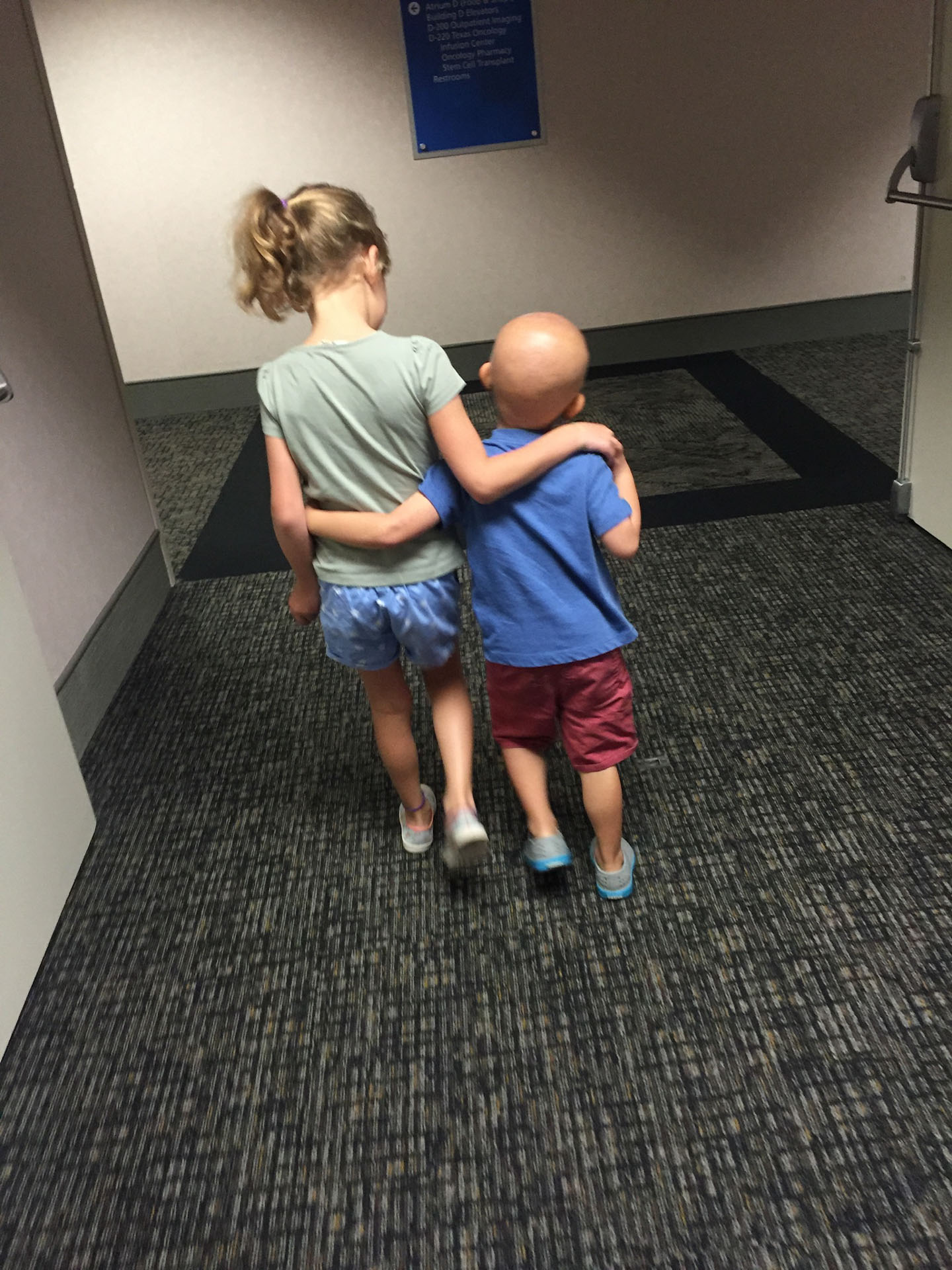

Sam lived at Cook Children’s about a month. Tony stayed with him during the weekdays, and Maude came on the weekends. Though he didn’t see his older sister, Emmie, at all while he was there, Sam set a record for the fastest recovery time — 24 days.

“That was Sam. Even amongst all these special kids we got to meet, he was a special kid,” Tony says.

For 18 months, Sam was in remission even as he continued treatments. Over the summer, he played on soccer and tee-ball teams. But around Christmas, the toxicity of the immunotherapy treatment he was undergoing prevented him from breathing on his own. He also developed a respiratory virus and had to be placed in an induced coma for about two weeks so a breathing machine could help his body to recover.

Sam came out of the coma and had to regain the strength to walk and talk again. But his body wasn’t the same, and he never was able to keep up with other kids.

“That’s the stuff I remember, was being proud of seeing him out there but then also feeling for him,” Tony says. “And he didn’t care. He didn’t care that he couldn’t keep up. He would do everything he could until he got tired, and then he would just plop down wherever he was.”

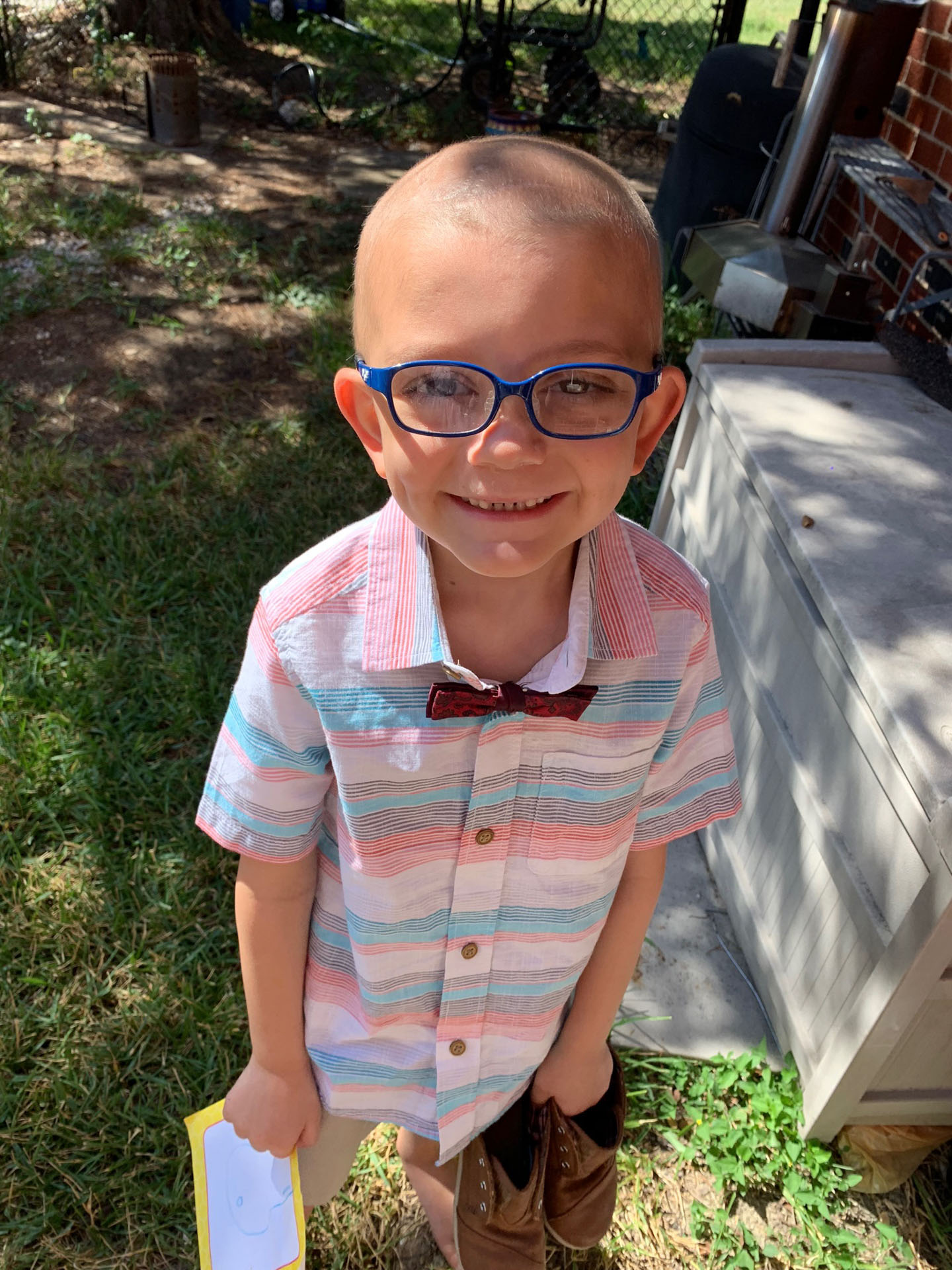

Being cancer-free meant he could start kindergarten. When he was first diagnosed with cancer, Maude feared that was something he would never be able to do.

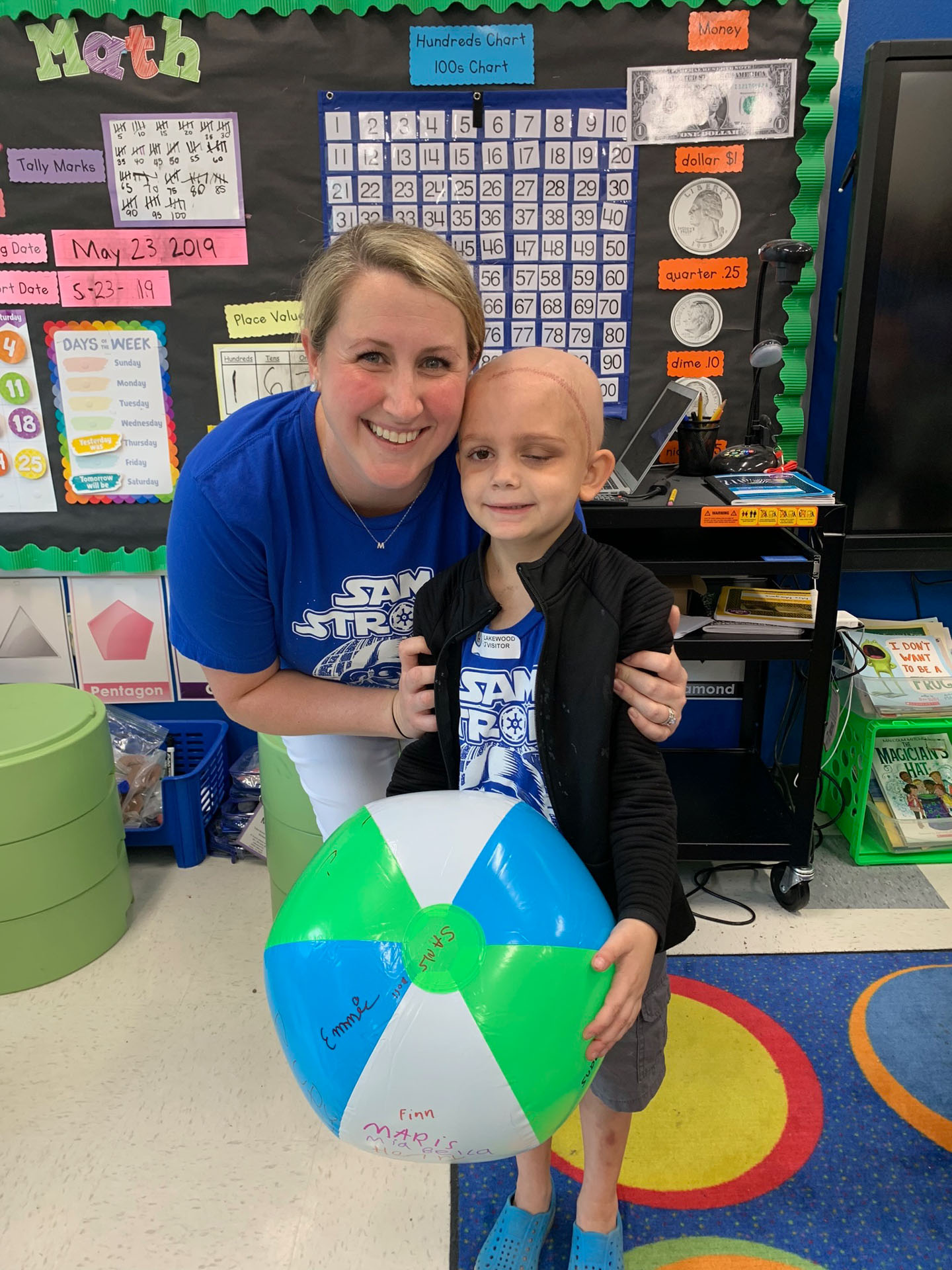

At Lakewood Elementary, Sam — smart and curious — found new independence. He walked around campus, hung out with his friends and was proud to go to school.

During that year, they realized Sam had some hearing loss as a result of an earlier treatment, but there were plenty of accommodations. Sam had a hearing aid, he sat at the front of the classroom, and his teacher used an FM system to amplify her voice.

Toward the end of the year, Maude was pregnant with Ben, their third child, when Sam, now 6, relapsed again. A 4-centimeter mass was pressing against his optic nerve.

They met with a neurosurgeon to talk about treatment. Should chemotherapy be administered to try to shrink the cancer? Should surgery be done first? Radiation?

Sam calmly sat up and said he couldn’t see out of his eye. Surgery first, they decided, and began discussing when it would happen.

“Let’s not talk about it. Let’s just do it,” Sam said.

“He was always ready to take whatever that next step was, and let’s just get it done, and one step after another one,” Tony says. “He was my action kid, is what I called him.”

Photography by Corrie Aune.

Because the cancerous mass was so close to Sam’s brain, they decided to take him to a place where he could get specialized treatment — Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Doctors put a catheter in Sam’s skull, allowing chemotherapy to bypass the blood-brain barrier and go directly into his brain and spine. Tony and Sam commuted to and from New York and Dallas. Whenever Sam wasn’t getting treatments, an organization called Candlelighters of New York arranged special activities, like a personal tour on the Hudson.

Around Christmas in 2019, when Tony’s family was in town, the Pampels noticed Sam seemed to have particularly low energy.

Then on Jan. 2, Sam woke up screaming in pain again. They went to a Dallas hospital and learned he had bacterial meningitis. The port in his head, which was allowing medication to treat the cancer, had become infected.

That began Sam’s longest stay in a pediatric ICU. Doctors administered antibiotics and put a shunt in his head to allow fluid to be expelled from his brain, which wasn’t properly balancing the correct amount of cerebrospinal fluid.

One day, Tony was at the hospital with Sam and the neurosurgeon, who was meeting with them to discuss how the shunt was working. But there was something else.

“He showed me where the cancer was making a very, very aggressive return,” Tony says. “And he also explained to me that because of the damage caused by the bacterial meningitis, all of our treatment options were blocked, and that there was nothing further they could do for Sam.”

Sam had maybe weeks, probably days left to live. Tony and Maude initially hoped to take him home, but they realized it wasn’t possible, and they were transferred to a different floor, out of the ICU. Sam had the biggest corner room, with two beds pushed together, familiar faces in the nurses caring for him and every day, a view of the sunset.

“I think you start to change your mind, and you realize as you walk through it the best decision for your family and for him, what was going to be the best,” Maude says.

The family spent the next six days with Sam. Though he was receiving a lot of pain medication, he was coherent. He ate only one dish, crunchy pudding — chocolate pudding with Honey Nut Cheerios — and was always making jokes.

Once, when everyone thought Sam was asleep, he popped up, held open his eyelids (because he lost the ability to open his eyes normally after the surgery) and said: “Hey, dad. What did the nacho say to the taco?”

“I don’t know, buddy,” Tony replied. “What did he say?”

“That’s nacho cheese.”

Another time, a priest came to the hospital to deliver last rites. As he was putting chrism oil (holy anointing oil) on his forehead, Sam said: “Not yet.”

Sam died Jan. 23, 2020.

At his funeral service, the cathedral at Church of the Incarnation was “packed to the gills.”

“I wish we could find a way for every kid that was dealing with this and every family that’s supporting them to have that level of support,” Tony says.

In September 2020, to honor his son, mark National Pediatric Cancer Awareness Month and raise money for Alex’s Lemonade Stand, Tony decided to make a daily 3/4-mile walk around the neighborhood. It’s the same distance he and Sam walked every day while they were in New York from the Ronald McDonald House, where they were living, to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and back.

Armed with a selfie stick and needing a way to share his story, Tony live-streamed the neighborhood walks. He talked to Facebook followers about Sam, his family’s experiences and the organizations that helped them.

On one of the last days of the month, Tony walked out of his house and saw about 20 friendly faces waiting to walk with him. As they headed to the alley, where the walk began, another 50 people were there to join them.

“We received so much from the community, people we didn’t even know …” Tony says. “Community became just such a huge part of our life and helped us in so many ways.”

The Foundation

Sam Pampel’s story didn’t end Jan. 23, 2020, when the 7-year-old neighborhood child died of brain cancer.

And it still hasn’t.

His parents, Tony and Maude Pampel, wanted to give back to the tremendous support system that had helped their family over the past four years and still does today: organizations dedicated to supporting patients and their families; the Pampels’ own family; friends; Emmie’s godfather, who’s a pediatric oncologist; and Maude’s colleagues, who are physical and occupational therapists. The Lakewood Elementary community even stepped up, with almost everyone wearing “Sam Strong” T-shirts on Superhero Day.

“I wish we could find a way for every kid that was dealing with this and every family that’s supporting them to have that level of support,” Tony says.

They created the Samuel Allen Pampel Foundation in September 2021, though they started talking about doing something while Sam was still alive.

“The community that followed Sam and everybody that touched Sam — that Sam touched, too — they always wanted to know how they could help,” Maude says.

“And they were always involved in supporting us. And we just felt that this was a continued way that we could help ensure Sam’s legacy and support these organizations.”

The community kept asking for more opportunities to help, and the Pampels support multiple organizations. It was hard to focus on raising funds for just one group at a time, so rather than trying to raise money for several all at once, the Pampels decided to establish their own foundation and distribute funds themselves.

Sam’s nanny wanted to host a 5K race to benefit one organization, and that event became the first fundraiser, which they held at Bachman Lake on Sam’s birthday, Nov. 6. They figured 50 or 100 people would participate. But 384 registered, and the race generated $35,000 for Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer, Candlelighters of New York, Camp iHope, and the Grief and Loss Center of North Texas.

When Sam was sick, Alex’s Lemonade Stand helped cover the Pampels’ travel expenses. Camp iHope has been a fun place for Emmie to go to camp, along with other siblings of kids who have cancer. And the Grief and Loss Center helped the whole family after Sam died.

The Pampels hope their work will spread the word about these and similar organizations to people who probably have never heard of them.

“If we can make life just a little bit easier while we try to find the research and answers — because the cancer, no matter how much money we throw at it, is not going away tomorrow — and so we want to support research and get rid of that,” Tony says.

“But in the meantime, for those families that are on the front lines, how can we just take one piece of the burden off their shoulders?”