The club scene blackened Lower Greenville’s reputation, but neighbors who defended their home turf are starting to see the light

At almost 2 a.m. on a weekend in 2006, Angela Hunt sat in the living room of a friend who had called for help.

Her friend lived a few houses down from Lower Greenville, which was a madhouse that night, just like it was every weekend that year. Hunt, an M Streets resident who, at the time, represented the area on the Dallas City Council, couldn’t believe the amount of noise permeating the home. It was out of control.

Then, suddenly, the pair heard glass shatter in the street out front.

“So I run out there and there are these nicely dressed, well-heeled little frat boy shits walking and laughing with a couple of girls,” Hunt recalls.

Hunt yelled at them, demanding to know if they had thrown the bottle, but they just cussed and flipped her off.

Frustrated, she followed the troublemakers down the street and called a Dallas Police sergeant, requesting his help. When the police showed up, they walked the boys back to the house and made the young men apologize.

Hunt introduced herself as a city councilwoman and told them she didn’t appreciate them damaging property in her neighborhood. She asked one of the young men why he had thrown the bottle. He shrugged and answered earnestly, “Well, look around; it’s everywhere.”

“And that really struck a chord with me,” Hunt says. “This broken-window theory, like if a neighborhood has a lot of broken windows or a lot of trash or junk in the yard, there’s this sort-of theory that this is not a well-maintained area. It’s kind of ripe for the picking.”

That’s what was happening to Lower Greenville, Hunt believes. In the early 2000s, Greenville began to experience more and more crime, graffiti and litter, which only served to perpetuate the cycle.

“This kid — who was dressed in this nice, crisp polo shirt and certainly would never throw a bottle on his own street — saw this as a trash heap where he and his friends could come and throw bottles on the ground, and it wouldn’t mean anything to anybody because this was just a dump,” Hunt says.

That was a lightbulb moment for Hunt, she says. Something needed to change — and fast. The problems were growing worse, especially on Lowest Greenville, the stretch from Ross to Belmont, where police swarmed every weekend in an attempt to stamp out all manner of crime — underage drinking, DWI, assault, murder, robbery, vandalism. Neighbors and business owners who witnessed the worst years first-hand remember it as a “war zone.”

Hunt began talking with neighbors, business owners, landlords and anyone else invested in the area to try to figure out a comprehensive way to shut down crime. Finally, in 2011, city involvement brought Greenville to its knees.

Today, on any given afternoon, Lowest Greenville bustles with daytime activity — neighbors picking up a few groceries at Trader Joe’s, meeting friends for lunch at HG Sply Co., or staving off the heat with a gourmet popsicle from Steel City Pops.

Later in the evening, the avenue continues to draw crowds to its newer, more low-key night scene. After the sun goes down, hundreds of folks perch on the rooftop bars, crowd the picnic tables at The Truck Yard, and stop in for a drink or two at some of the more divey spots, such as The Old Crow or Crown and Harp.

These days, people young and old alike feel safe eating, drinking or shopping on Lowest Greenville at any hour. To some, it’s a shining example of what can happen when a neighborhood comes together.

But even while they bask in the glow of Greenville Avenue’s rebirth, neighbors are still grappling to understand how things spiraled out of control — and working to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

The daytime-to-nighttime shift

Greenville wasn’t always an entertainment district. Like many neighborhood shopping centers, it originally was developed for daytime use.

Before Central Expressway was built in the 1950s, Greenville Avenue was one of the main roads through Dallas, so Greenville was a major hot spot for shopping and restaurants, conveniently snuggled among residential neighborhoods for walkability purposes.

“If you look at the way Lower Greenville was originally zoned and developed, that was intended to be a neighborhood retail strip,” Hunt says.

The strip consisted mainly of service retailers — grocery stores, convenience stores, barbershops, a shoe repair shop, a furniture store and a smattering of restaurants and clothing stores.

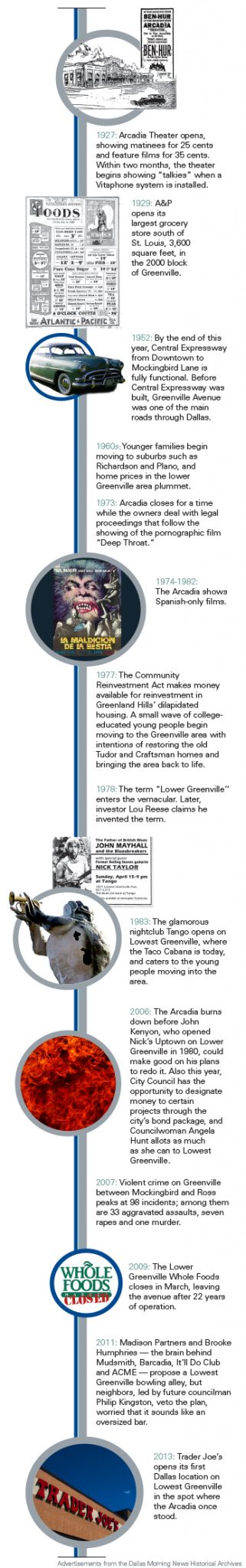

Arcadia Theater, which opened in 1927 where Trader Joe’s is today, was a neighborhood staple. It showed its first “talkie” the same year when a Vitaphone sound system was installed, and neighborhood children would walk a dozen or so blocks to catch a 10-cent flick.

In the ’60s, the residential area surrounding Greenville hit an economic decline when young families began moving to suburbs such as Richardson and Plano. Then, in the ’70s, a small wave of college-educated young people began moving to Lower Greenville with intentions of restoring the old Tudor and Craftsman homes and bringing the area back to life.

Ken Lampton and his wife, Jane, were among them. They moved to the area in 1979, right around the time investor Lou Reese coined the term “Lower Greenville.” At the time, Lampton remembers, pawnshops, thrift stores and the like were the primary retailers along the strip of Greenville between Belmont and Ross. There were a few bars and clubs, but not any establishments that interested the area’s young folks.

“We wanted to fix up a very old house that was in very bad shape,” Lampton says. “It sounds crazy, but that was our dream. We were like crusaders. That meant that not only did the houses get fixed up, but also that new retail went in on Greenville.”

The gentrification of Lower Greenville was fully apparent by the ’80s. Lampton remembers major turning points, such as investors purchasing the circa 1931 building that houses Terrill’s “as they realized there was a new demographic coming into the neighborhood,” he says. Another was the 1983 launch of Tango, a glamorous nightclub that occupied the space where Taco Cabana sits today. Though it closed about a year later, neighbors still mention it as a highlight. Even Lampton, who never actually patronized Tango, recognized that the club represented a new era for Lower Greenville: Instead of dusty old pawnshops, investors were opening bars and eating establishments, which meant young people like Lampton, who had taken a gamble by buying property in the area, had made a good investment.

The gentrification of Lower Greenville was fully apparent by the ’80s. Lampton remembers major turning points, such as investors purchasing the circa 1931 building that houses Terrill’s “as they realized there was a new demographic coming into the neighborhood,” he says. Another was the 1983 launch of Tango, a glamorous nightclub that occupied the space where Taco Cabana sits today. Though it closed about a year later, neighbors still mention it as a highlight. Even Lampton, who never actually patronized Tango, recognized that the club represented a new era for Lower Greenville: Instead of dusty old pawnshops, investors were opening bars and eating establishments, which meant young people like Lampton, who had taken a gamble by buying property in the area, had made a good investment.

In the late ’80s and ’90s, Lower Greenville slowly carved out a reputation as an entertainment district. The Arcadia Theater became a concert venue, which is how many East Dallasites remember it before the devastating 2006 fire. More bars and clubs began to open on the avenue, drawing people from all over Dallas who were eager to revel in its up-and-coming night scene. Some people consider the ’90s Lower Greenville’s heyday, including Mike Schoder, co-owner of both Granada Theater and Sundown at Granada on Greenville. Schoder began frequenting the strip during the ’90s and early 2000s, when his brother, Kerry, bartended at the now-closed Billiard Bar.

“We used to go down there after watching shows at the Granada, at about midnight or 1 o’clock in the morning, you know, have a last drink before you go home,” Schoder recalls. “It used to be all the pretty girls, all the pretty people, all the cool restaurants and bars.”

Neighbor Patricia Carr and her husband moved to Lower Greenville in the ’70s from University Park. She has witnessed the area’s evolution, and even played an active role in its transition, especially during the last six years as the Lower Greenville Neighborhood Association president. For many decades, the avenue managed to maintain a balance between daytime and nighttime business, Carr says. Then, around the turn of the century, she remembers a shift: Bars and clubs could make more money than daytime retail, and soon they dominated the strip between Belmont and Ross. Eventually, irresponsible business owners began to proliferate, Carr recalls. These so-called “bad operators,” as neighbors often refer to them, were known for over-serving underage drinkers cheap alcohol.

“The area became known for these establishments, rather than the responsible businesses that were there,” Carr explains, “and the responsible businesses that were there started moving out.”

Much has changed but some things have stayed the same on Lowest Greenville, as evidenced by these circa 1930 and present-day photo by Danny Fulgencio that look north onto the avenue. (Historical image from the collections of the Texas/Dallas History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library)

A normal street to Bourbon Street in five minutes’

Lowest Greenville especially began to garner a reputation for selling alcohol to underage drinkers, which attracted more underage drinkers, which brought in more money to the bad operators.

Lowest Greenville especially began to garner a reputation for selling alcohol to underage drinkers, which attracted more underage drinkers, which brought in more money to the bad operators.

“Bars and clubs are in the business of making money,” says Dallas Police Detective Keith Allen, who has fought crime on Lower Greenville for roughly 20 years. “The way for these establishments to make money is for them to cater to a younger and younger crowd.”

Young people from all over the city flocked to Greenville because they knew they could have fun and get into trouble relatively unchecked.

“From 2005 to 2007, it was mostly an SMU crowd,” says neighbor Lee Escobedo. “I used to spend a lot of time down there in the only three-piece suit that I had. I’d wear it every Saturday night and try to mac on SMU girls — to some success. Some. Stumbled in the street. Got kicked out of bars a lot.”

During that time, Lower Greenville consisted mostly of dance clubs, he says, but the vibe changed in the late 2000s.

“A lot of people started leaving because some of the bars that popped up were becoming notorious for places where drug dealing was going on,” Escobedo says. “The street had a different feel to it. There were a lot of people fighting in the clubs, fighting on the streets. It was bad.”

Schoder, too, remembers when the avenue started drawing a “late-night crowd that liked to fight, that liked to pull knives and guns.”

“It got to the point where we wouldn’t go down [to Lowest Greenville],” he says. “You’d be sitting on the patio, and a fight would break out in the street. All of a sudden, it felt like a bit of a war zone. It’s incredible how that can happen so quickly.”

Greenville’s activity was a formula for violent crime, Allen says: “When you have a relatively small stretch of property that’s dominated by alcohol-centric bars and restaurants, and then on top of that you’re catering to a younger group of 18- to 20-year-olds, those were the things that caused the problems,” he says. “The violent crimes that were taking place around closing time were primarily because of the younger groups of people that were being catered to.”

Allen says this type of situation is not unique to Lowest Greenville.

“Anytime you take that model, you could move it anywhere and you’d have the same issues,” he says.

Darren Dattalo with the Lower Greenville Crime Watch says that during the “bad years,” he would head to the Char Bar on crime-watch business and sit in the parking lot to watch the drama unfold.

“The street would seem kind of normal, nothing too bad, and then about a quarter to 2 a.m., you would start seeing the drunks coming out,” he recalls. “Right at 2 o’clock, there was this huge police presence. They would come out with military precision and put cones on the street and start directing traffic, because the street would go from what looked like a normal street to Bourbon Street in five minutes.”

Hundreds of people poured out of the bars onto the street, which resulted in complete chaos for the next hour and a half, Dattalo says, while police tried to direct people out of the area.

“Then all the frustration of all these drunk people out in the street at the same time ended up turning into fights in the parking lot,” Dattalo says. “One night I was out there and there were three unrelated fights going on simultaneously in three different areas.”

Some of the bar-goers even pulled knives or guns, he says, and there were incidents of people driving by and shooting at people in the crowd.

As violence escalated on Lowest Greenville, folks living in the surrounding residential neighborhoods grew increasingly concerned about their safety.

“Residents were not really inclined to go walking their dogs at night because they were afraid they were going to get mugged,” Carr recalls. Not only were bar-goers being noisy, littering, vandalizing property and peeing in people’s yards, she says, “but there was also a very real physical danger.”

Carr remembers a time when she wanted to host a luncheon at a restaurant on Lowest Greenville, but the other lunch-goers objected, saying the area was too dangerous. She also vividly remembers an email from one man: “ ‘I’m afraid for my children because I go out on my patio on Sunday morning and there are bullet holes in my hot tub.’ And of course, residential property values began to plummet because people didn’t want to live next door to a war zone,” Carr says.

An erstwhile tapas bar on Lowest Greenville is symptomatic of the ebb and flow of business on the avenue: Photo by Danny Fulgencio

The city began attacking the crime and bad operators on several fronts. Madison Partners and Andres Properties, who own almost all of the property along Lowest Greenville, worked to ensure that their renters were good operators, but other Lowest Greenville landlords weren’t as careful.

The city began attacking the crime and bad operators on several fronts. Madison Partners and Andres Properties, who own almost all of the property along Lowest Greenville, worked to ensure that their renters were good operators, but other Lowest Greenville landlords weren’t as careful.

Bringing peace to the ‘war zone’

Back then most of Lowest Greenville had wider lanes, narrow sidewalks and head-in parking, similar to the parking you see today in front of The Libertine Bar, rather than parallel parking. “It wasn’t walkable by pedestrians, and it was really ugly and dirty and tacky,” Hunt recalls.

Philip Kingston, who took Hunt’s place on the Dallas City Council last year, says he believes the city is to blame for allowing the streets, sidewalks and other aesthetic elements in the area to fall into disrepair.

“I believe that disincentivized landlords from keeping their buildings up,” Kingston says. “Why would they put money in if they don’t have a reasonable expectation of return?”

This was the recipe for the “broken windows theory” to which Hunt often refers. The avenue looked bad, and so — like a self-fulfilling prophecy — it became bad.

In an attempt to patchwork the problem, the city began spending hundreds of thousands of dollars every year on a heavy-duty police presence in the area, Hunt says — just to keep people from literally killing each other. At times, police even went so far as to PepperBall crowds of bar-goers in order to defuse dangerous situations, Allen says.

That happened in front of Greenville Avenue Pizza Company one night, say owners Sammy and Molly Mandell. When a fight broke out and police began spraying, they scrambled to get people inside and lock the doors. “It was crazy down here,” Sammy says of those days. “The clubs were packed out with lines out the door. As a pizza place that was open past 2, every night it was just like, ‘Get ready.’” Some places weren’t even busy until the wee hours, when bars began offering 50-cent shots, they say. “At midnight, all these people would converge on this little strip, get completely hammered out of their minds, and then it would just be complete craziness until 3 a.m.,” he says.

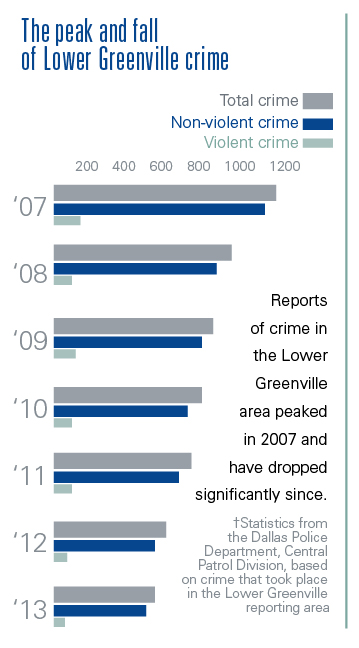

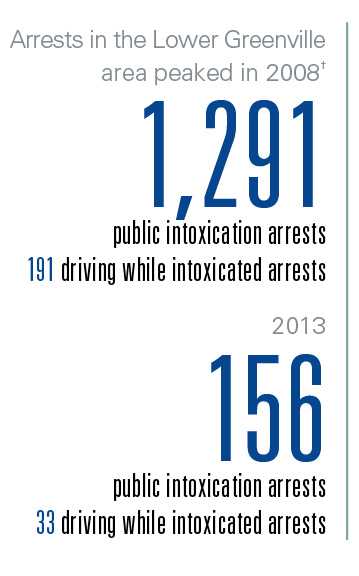

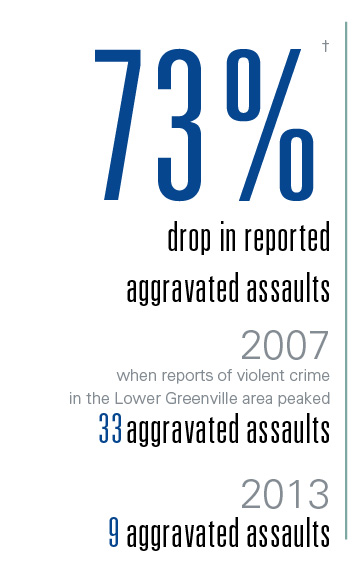

The crime numbers speak for themselves. In 2007 violent crime on Lower Greenville between Mockingbird and Ross peaked at 98 incidents; among them were 33 aggravated assaults, seven rapes and one murder. Those numbers don’t include another 1,077 non-violent crimes. In 2008 public intoxication arrests hit a high of 1,291, and DWI arrests rose to 191.

As police spent nearly every weekend dispersing the drunken mobs, the city concurrently worked to smack down some of the rowdier establishments, but Hunt describes that task as an exhausting and pointless game of whack-a-mole.

“We could attempt to prove that they weren’t really restaurants; that they were really bars, which would require them to get an additional permit from the city. That would give us [the city] a little more authority,” Hunt says.

But as soon as the city took one “restaurant” to court, the owner would shut the establishment down and a brother-in-law or cousin would open up in the same location as another “restaurant,” Hunt says.

“So there was really no legal tool that we had at our disposal to address this in any kind of comprehensive way,” she explains. “It was clear to me that we were playing a game, and we weren’t half as good at it as the bars were.”

The city needed a more comprehensive approach, Hunt believed, if it ever hoped to make a serious dent in the spiking crime rates. One day while playing around in Google SketchUp, which is basically a design tool for non-designers, Hunt re-created Lower Greenville — only better.

“I looked at what it could be, and it was amazing,” she says. “It was this pedestrian-friendly, fun little street that could be attractive to neighborhoods and restaurants. It could have mom-and-pop antique shops or local restaurants like we had on middle and upper Greenville. The idea of that was very exciting to me, but it was getting there that was the challenge.”

In the city’s 2006 bond package, council members had the opportunity to designate money to certain projects, and Hunt allotted as much as she could to Greenville. She hoped to work with neighbors and business owners to eventually reach a point where it would be worthwhile for the city to invest in major infrastructure improvements.

Hunt partnered with Pauline Medrano, a fellow councilwoman whose district also included part of Lower Greenville, and they approached the major players — neighborhood association leaders, business leaders and property owners. Their plan was to rezone Lowest Greenville, from Belmont to Ross, as a Planned Development (PD) District and force late-night businesses to apply for a Specific Use Permit (SUP) in order to stay open past midnight, which would allow neighbors and other nearby business owners to voice their opinions about the restaurants and bars seeking a permit. This would hold businesses known for crime to a higher standard of accountability.

The carrot was that the city would rebuild the area to make it a pedestrian oasis, Hunt says.

“I said, ‘We want to make these improvements, but there’s no way that I’m going to make these incredible and dramatic changes for bars, just to make it easier for the frat guys to drunkenly walk down the street,” Hunt says. “I’m not going to do it, because there are other places in the city where I could put that money.’ ”

If Greenville wanted infrastructure improvements, it had to help her turn her case-by-case whack-a-mole mallet into an all-encompassing rat poison.

Good riddance, bars — hello, Trader Joe’s

Carr remembers about 150 people showing up for the first community meeting.

“There were a lot of people who were against it, and there were a lot of people who were afraid of it. They were afraid it would kill the reputable businesses,” she says. “Some of the business owners who were running responsible businesses expressed concerns, and I don’t blame them. I would have had the same concerns.”

The Libertine Bar, which opened on Greenville in 2006, was hailed as the ideal for how a good neighborhood pub should operate. Mike Smith, who co-owns the Libertine, says he “felt fairly positive” about Hunt’s plan because he believed Greenville had incredible potential, but Libertine was held to the same standard and scrutiny as everyone else.

“Anyone could’ve come along and said, ‘No, I don’t like Libertine,’ ” Smith says. “That could’ve happened, but it didn’t. We had a lot of reassurance from the neighborhood and the city that we didn’t have anything to worry about, that they appreciated our business. But of course when you have money on the line, you get a little bit nervous.”

What really stands out in Smith’s mind is the awkwardness of the first meeting.

“There were people you could point out and be like, ‘Yeah, that guy is not going to be there. They’re clearly trying to squeeze that guy out,’ ” Smith says.

Because of that, Hunt received a lot of pushback from business owners. So she focused her efforts on working with the primary property owners, Andres Properties and Madison Partners. Hunt says both landlords had been burned by the city previously in a permitting process over parking issues.

“We were very nervous right up to the end,” says Jon Hetzel with Madison Partners. “It puts a lot of private property rights on our end into the neighborhoods’ hands without reciprocating on anything, in our minds. Neighbors weren’t giving us much, and we were giving them a lot of our private property rights.”

But Madison Partners caught on to Hunt’s vision for the avenue.

“We absolutely, 100 percent agreed with the vision. We were nervous about the tool,” Hetzel explains. “Because we had next to no bar tenants, we weren’t necessarily even scared about losing our tenants. We were more concerned about not being able to put in interesting tenants that wanted to be open past midnight that weren’t really operating as bars.”

In other words, Hetzel says, “we were afraid of the baby getting thrown out with the bathwater.” But Hunt promised Andres and Madison “a different type of renter” and “a different set of clientele that aren’t going to bring the graffiti, trash, crime and noise issues.” The two major players decided to get behind her plan.

“It was challenging to get their buy-in, but we did,” Hunt says. “Without their support, it really wouldn’t have happened.”

She also approached leaders of the surrounding six homeowners’ associations — Lower Greenville, Belmont, Hudson Heights, Lowest Greenville West, Vickery Place and Greenland Hills — and made the same promise.

“When I went to neighborhoods, I told them, ‘I will fight this until my nails bleed. I’ll do everything I can to get this, but I have to know you’re with me.’ And they were, every step of the way,” Hunt says.

It took a lot of twisting, turning and tweaking, but in the end Hunt and Medrano’s efforts came to fruition, and the Lower Greenville Planned Development District was approved in January 2011. By that time, many of the “bad operators” had seen the writing on the wall and already closed their doors. In fall 2011, Yucatan (formerly Malibu Bar), Shade, Service Bar and Soprano’s were denied late-hours permits, according to Carr. Four others that had high police activity — Lost Society, 180 Degrees, Sugar Shack and Hotel Capri — just packed up and moved away without even applying for a permit, she says.

For a time, the strip seemed achingly empty, but the city kept its promise to renovate the area. The City of Dallas approved a $1.3 million makeover to refurbish Greenville Avenue and its sidewalks, plus add other aesthetics. Between Bell and Alta, four lanes were narrowed to two in order to widen the sidewalks. Street parking was re-rigged from head-in to parallel. Property owners Andres and Madison even chipped in to help move telephone poles from the avenue’s sidewalks to the back parking lots.

Then, in December 2011, Trader Joe’s, which, according to Hetzel, had been keeping its thumb on the Lower Greenville pulse for more than a year, announced it would make the avenue its first Dallas location. The California-based gourmet grocer was a catalyst for change on the avenue, ushering in a tidal wave of daytime businesses.

In early 2013 hipster coffee shop Mudsmith opened right across the street from where Trader Joe’s was being constructed. Soon after, paleo-centric restaurant HG Sply Co. opened its doors down the block, and its owners have been building a small empire ever since — the Social Mechanics gym next door, a gigantic rooftop bar, and an old-fashioned soda fountain slated for later this year. Trader Joe’s opening in August 2013 was quickly followed by an announcement from Matt Pikar, owner of Nora Restaurant and Bar, that he and his wife, Rosalind Lynam, would expand their restaurant with a private dining room and rooftop bar. The dominoes continued to fall — The Truck Yard; Dude, Sweet Chocolate; Crisp Salad Company; Blind Butcher; Steel City Pops and three more new restaurants being built next to Trader Joe’s.

“I just love seeing people come back to Lower Greenville,” Hunt says. “I’m absolutely the proudest of that project. A lot of other things in the city happen with or without you, to be very honest. That is something I’m proud of because I feel like I got to play a part in it, and that’s exciting to get to play a part in something that has transformed an area. Hopefully, it will have a long-lasting impact.”

A success story (for almost everyone)

Everything seems to be working out as Hunt hoped. Or better than she hoped, even.

Hunt says she believes Greenville will continue to be successful because the SUP process acts as a partnership between business owners and the city to ensure that no more bad operators will be allowed within that stretch.

But some people have reservations. Chuck Cole, both a neighborhood resident and owner of Corner Market, has watched the changes quietly. Although his shop is north of the PD, he understands what it takes to run a small business, which makes him wary of the stronghold the city has over Lowest Greenville.

Though Cole thinks the positive changes are great, he worries the current setup isn’t sustainable because “the SUP is running off really good tenants.” Cole believes the bowling alley proposed in 2011 by Madison Partners and Brooke Humphries — the brain behind Mudsmith, Barcadia, It’ll Do Club and ACME — would have been a good addition to the avenue. But neighbors shot it down through an effort spearheaded by Kingston because it sounded like an oversized bar.

Hetzel admitted that it has been “a little harder to lease to businesses, not being able to promise that they’ll be able to open after midnight,” although he says Madison hardly lost any tenants when the SUP process kicked in, except club Shade, which was replaced by Mudsmith.

Because the SUPs help ensure balance along the avenue, Hetzel thinks the process is a good thing overall, although it can negatively impact a business’s bottom line.

“Truck Yard is a good example of a business that could make a lot more money if they were open after midnight,” Hetzel points out, “but they’re closing at midnight, and that’s fine. They’re making tons of money. I think if it was politically realistic, they would stay open after midnight, but I don’t think it is.”

Most of the new Lowest Greenville businesses have been welcomed with open arms, but a couple have had a more difficult time gaining neighbors’ trust. Blind Butcher, which opened where the Service Bar was once located, is one of those businesses. With the rowdy activity of the Service Bar fresh in their minds, nearby neighbors were skeptical of the new craft beer-centric joint — no matter how much the owners, who also operate Goodfriend on Peavy, promised to be good neighbors.

When Blind Butcher opened in February, its SUP allowed the restaurant’s interior to operate until 2 a.m., but the back patio had to close at midnight. Since then, almost everyone agrees Blind Butcher is, indeed, a good business. However, a few neighbors aren’t as fond of the patio. When the restaurant owners’ request for a late-night permit went to a public hearing before the City Plan Commission earlier this year, several neighbors testified that they are awakened regularly by voices bouncing off the patio’s walls and into their bedrooms. The commission voted to give Blind Butcher a 1-year trial to keep the patio open until 2 a.m., but when the request went before City Council, Blind Butcher pulled it and instead settled for a 3-year renewal of its current arrangement, which comes with an automatic two-year renewal if the restaurant keeps its end of the bargain. In essence, Blind Butcher opted to sacrifice potential revenue in hopes of avoiding a confrontation with the city (and neighbors) for another five years.

Mediterranean restaurant Kush is another late-night establishment that has felt the sting of the SUP backlash. Its late-night permit expired last fall and wasn’t renewed because “the people around us, they all voted against us,” says manager Farhad Ata, whose family owns the restaurant and hookah bar.

Ata blames a fatal stabbing near its 2 a.m. closing time in August 2013. Although the incident didn’t involve Kush, it happened right outside, so neighbors tied the murder to the restaurant, Ata says. Neighbors, however, cite not only the stabbing but also a continued record of violent crime around Kush as their reason for opposing the SUP.

Kush plans to remain on Lowest Greenville, even though closing its doors at midnight has meant taking a major financial hit.

“Sixty percent of our business happened after midnight,” Ata says. “People would come to Greenville, have dinner, and then come here afterward and have some drinks and hookah.”

The SUP places the power in the hands of the neighbors and the city.

“Everyone wants lights out at midnight, but you don’t want 100 percent restaurants, just like it wasn’t good as 100 percent bars,” Cole points out. “But now that natural market is gone because of the SUP. A lot of the places, like me, I would never ever, ever do that. It would have to be a phenomenal opportunity before I would submit to [an SUP]. If they ever try it up here [further north on Greenville], you will see the fight of the century.”

Blind Butcher co-owner Matt Tobin admits that dealing with a handful of neighbors who dislike the activity on Lowest Greenville — particularly because of the recent spike in noise and traffic — has been disenchanting. However, he says, “we realized where we moved to.” Despite the neighborhood backlash, Tobin says Blind Butcher is “fully on board” with the SUP process.

“We all are,” he says. “You would be hard-pressed to find any new business owners down here who have any problems with the way that they got rid of businesses. It’s a good thing. The problem, though, is that the idea was to get out the bad operators. And it did. They’re gone.”

In contrast, Tobin says, “We’re doing a really good job, providing a cool service to the neighborhood, along with other people down here who are trying to make [Lowest Greenville] come back up.”

Lindsay Dyer, also with Blind Butcher, points out the “interesting juxtaposition” of neighbors trying to be proactive so Lowest Greenville doesn’t get out of hand again.

“They’re also retroactively punishing the businesses that don’t want to be a problem at all,” she says. “So they’re scared of what could happen, even though that’s not what’s happening.”

In order to give the business owners a more unified voice, a young woman named Jessica Burnham has been working with them to coordinate a business association. Greenville and its challenges appealed to Burnham as an ideal project for her master’s degree at the University of North Texas, where she is studying applied design research.

Burnham started talking with neighbors last winter, and in February a handful of business owners began meeting somewhat regularly. In March they decided to officially form the Lowest Greenville Collective.

In August Burnham hosted a party to celebrate the launch of the new website: www.lowestgreenvillecollective.org.

A Greenville with ‘grandmas and baby carriages’

For the first time in years, neighbors feel comfortable walking to Lower Greenville. The area has seen a steady decline in crime; as of last year, violent crime had dropped nearly 90 percent since the 2007 peak, and non-violent crime nearly 80 percent.

Carr remembers Pauline Medrano once stating that she wanted to see the avenue “filled with grandmas and baby carriages.”

“And when I walk down the street, I see a lot of baby carriages. I’m the grandma,” Carr says, laughing. “There’s a lot of bike traffic. People walk now. They’re not afraid to walk a few blocks for dinner.”

One day as she waited to cross Greenville, the line of cars trickling down the avenue actually stopped to let her pass.

“It was a whole different attitude,” she says. “That would not have happened before.”

The metamorphosis will continue. Because the Lower Greenville PD stretches from Belmont to Ross, Hunt says neighbors can expect to see street improvements — narrower lanes, wider sidewalks, parallel parking, street trees — reach all the way up Greenville to Belmont and all the way down Greenville to Ross by early 2015.

What happened on Lower Greenville could be a template for other Dallas neighborhoods experiencing similar problems, Hunt says — as long as they have the same level of engagement, she adds.

“The incredible neighborhood participation is unique to East Dallas,” Hunt says. “This was the outgrowth of the neighborhood’s vision for the area. It wasn’t just the city coming in with a heavy hand and telling people — neighbors and business owners — what we were going to do.”

Lower Greenville Crime Watch’s Dattalo agrees that success was achieved only through collaboration.

“When we did this, it was not one person ramming it through,” he says. “It was Angela’s idea, and she pulled in a bunch of people. It was a real group effort to take ownership of a bad situation and make it better.

“Everybody had to give up something that they didn’t like in order to get what we got. It was one of the most consensus-driven efforts that I’ve ever seen in Dallas.”