Growing up, earning good grades, pursuing a talent and gaining college acceptance is tough, but imagine doing so in the face of abject poverty or an incurable disability or while you are the primary caretaker for a dying parent and your younger siblings. Hellish circumstances can become an excuse for teens to escape down a destructive, pain-numbing path. For a few neighborhood seniors who will graduate this month, however, hardship is reason to strive for a better future. Their determination, support from teachers and administrators, and, perhaps, the iron-will derived from a fight for survival has driven them to remarkable success.

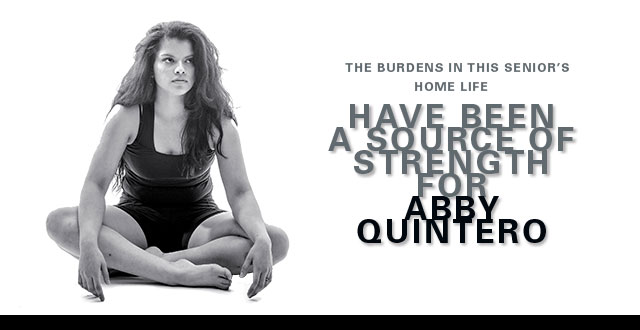

Woodrow senior Abby Quintero always lived in rough neighborhoods, but that hasn’t discouraged her from striving to become the first person in her family to go to college.

“When you live in poor neighborhoods, people always think badly about your future,” Quintero says.

She grew up speaking Spanish in her home, which kept her from being accepted into the Talented and Gifted (TAG) program for elementary school.

At home, things weren’t good for Quintero. When she was in the fourth grade, her parents got into an argument that escalated into abuse.

Quintero, her mom and her siblings moved into a women’s shelter, and Quintero had to switch schools. Her family could stay in the shelter only temporarily, and then they moved into a friend’s home, but that did not last, and they had to look for a more stable place to live.

The situation took a toll on Quintero. She learned English as quickly as possible, and by middle school her conversational English was flawless. Still, she wasn’t able to pass the test required to enter the TAG program for Alex W. Spence Middle School.

“I had a lot of burdens in my life, and that affected me,” Quintero says. “Also, I would always bomb the English part of the test, and that’s pretty essential to get into the TAG program.

“That was very unfortunate,” she recalls. “It made me feel bad about myself because it made me feel like, ‘I’m not good enough. I’m never going to be good enough because my grades are all that I have to depend on so that I can be better than what people say.’ ”

By the time Quintero reached Woodrow Wilson High School, she was frustrated with academia. During her freshman year, she began to rebel.

Not long after that she tried out for the drill team and became a Sweetheart (which is what Woodrow calls the members of its drill team) her sophomore year. Dance quickly became an outlet for her, to “distract her from everything else.”

That’s when she met Lisa Moya King, the dance teacher at Woodrow, who took notice of her.

“I could see that she was a leader because she would be dancing and everyone would be following,” King says. “I said, ‘OK, this girl has some potential.’ ”

When King began hearing rumors about Quintero’s behavior, King sat her down for a serious talk, hoping she could make Quintero see that she needed to make a change if she wanted to be successful.

That was just the intervention Quintero needed.

“For a teacher to tell you that they’ve noticed that, that they’ve heard rumors, and to talk to you about it, that was a big deal,” Quintero says, her eyes welling up with tears at the memory.

“I just burst out crying and said, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing with my life.’ I don’t know what it was about that discussion, but it only took one time.”

Quintero knew she needed to work harder if she wanted to succeed. Plus, she had to make good grades in order to dance with the Sweethearts at football games. Then she became an officer, which was a huge personal accomplishment. It also helped sharpen her natural leadership skills.

“She has these moments of complete abandonment, but also complete control,” King says. “There are a lot of layers to Abby, and it’s going to be fun to see where she goes in life. She has a good work ethic. She looks at what she wants and knows what it’s going to take to get there, but she wants it. She wants to do well.”

Quintero applied for Steven F. Austin State University, where she wants to major in hospitality and tourism. She found out on her mother’s birthday that she was accepted.

“Getting into college is the hugest thing I’ve ever accomplished. All that hard work, getting into college — I cried. It was like, ‘I don’t have to worry about anything any more,’ ” Quintero says.

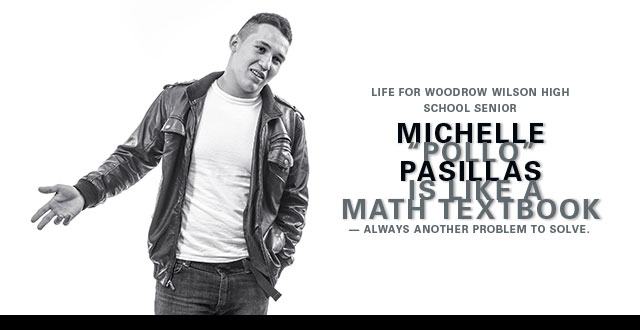

Luckily, the engineer-minded transfer student from Mexico is always up for a challenge.

Pasillas’ dream is to play in the NFL.

He was raised near Monterrey, Mexico, by his mother, stepfather and grandfather. Pasillas’ grandfather spent a significant amount of time in California, and then taught Pasillas and the rest of the family to play American football.

Pasillas planned to live with his uncle in California for high school so he could play football in hopes of earning a scholarship for college and a chance to be noticed by the NFL. Then his uncle lost his job in the financial crisis of 2007-2008, which put a sudden halt to the plan.

Pasillas continued with schooling in Mexico, learning as much English as he could while he waited for another opportunity.

He had been offered a scholarship to play football for the University of Monterrey in Mexico, but he doesn’t want to simply go to college; he wants to play in the NFL.

Finally, a family friend agreed to let Pasillas stay with her in East Dallas.

“My mom saw the opportunity and said, ‘Go ahead, if you really want to play football. You’re not going to be able to play football in Mexico,’ ” Pasillas says.

So Pasillas received a student visa and moved to Dallas, but his American dream quickly turned into a nightmare, because his host home was rife with drugs and other illegal activity.

“I will never try any drugs because of the situation in Mexico with the drug cartel,” Pasillas says. “I thought it would be safer here, and then I see this. There are people in my country dying for this.”

He got out of the home as soon as he could, instead sleeping at friends’ houses, at school, or occasionally on the streets.

“I don’t want to get caught in the wrong place with the wrong people,” he explains.

In the system change, Pasillas lost several key credits, and his A-average GPA transferred as a B-average GPA, even though he took advanced classes in Mexico. “I was doing calculus as a sophomore,” he says, “but they don’t give me that credit because it’s from Mexico.”

At first, Dallas ISD wasn’t sure what year to consider him, so they started him as a freshman, which allowed him to play for the football team. He proved himself on the field quickly and made the varsity team within a couple of weeks.

After a few months the school figured out Pasillas had so many credits that he was considered a fifth-year senior. Unfortunately, that meant he could no longer play football.

Pasillas was crushed.

“The whole point of all this struggle was to play football,” he says.

So instead, he threw himself into academics, making college acceptance his top priority with the hope of walking on to the football team. “When I get to college, a 3.2 isn’t going to be good enough. [Colleges] are going to see the same thing — a Mexican kid with bad English,” he says.

Although Pasillas was struggling with English, his strengths are math and science, so he joined the Science, Technology, Engineering Math (STEM) academy at Woodrow.

“I talked with Ms. Sanchez, and she speaks Spanish because she’s from Puerto Rico, and she looked at my transcripts and said, ‘You’re smart,’ ” Pasillas says. “It was like, thank God someone understands me!”

Sanchez advised Pasillas to enroll in AP chemistry and introduction to engineering. He had already learned most of the material that his classes covered, and his teachers began to take note of his excellence. He also joined the robotics team.

“I was in my environment because numbers stay the same,” Pasillas says.

The mindset that gets him through his math and science classes is the same one that propels him through high school.

“You have to solve the problem,” Pasillas says. “I don’t really know what’s going to happen to me; I just know that I’m going to be successful.”

He hopes to eventually go to Texas Tech to play football and major in engineering.

Pasillas’ grandfather passed away two years ago, but before he did, he taught Pasillas a valuable lesson that he clings to whenever he gets frustrated.

“My grandfather always told me, ‘Work hard or go home,’ ” Pasillas says. “I can’t go home, so I just have to keep working hard.”

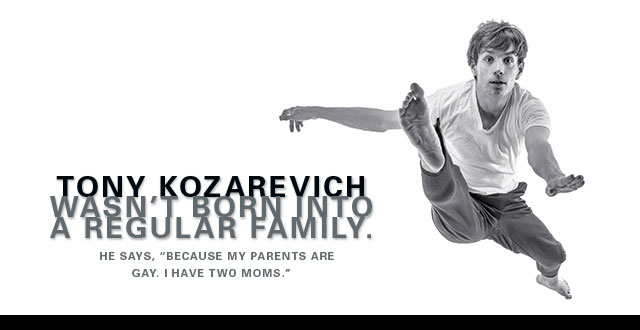

Growing up, it didn’t bother him that his family is different. Everything seemed normal to him until grade school, when it began to affect his social life.

One day he told a longtime friend about his two moms; the divulgence abruptly ended their friendship, Kozarevich says.

“To me, that was a slap in the face, because I didn’t know what was wrong with that,” he says. “And it didn’t stop there.”

Then the bullying started.

Bullies homed in on his love of dance, which he discovered in kindergarten. He took to it because he loved to move, he explains.

He continued to dance in grade school, and when the other students found out, they began calling him names.

“They started calling me gay, and to me that wasn’t a bad thing, but they kept trying to hurt me,” Kozarevich says.

Kozarevich told his teachers about one particularly aggressive harasser, and his parents even talked with the principal, but he says the school didn’t do anything to help.

Eventually Kozarevich snapped and punched the student. He was almost suspended, but his parents successfully argued for leniency.

After that, the bullying stopped until he switched schools. He began attending Sydney Lanier Expressive Arts Vanguard in fourth-grade.

“When I found out dance was a class, I immediately went there. There was no question about it,” he explains.

Although he was still called names, he found friends within the dance community, and he began learning how to brush off people’s hurtful comments.

And then came the eighth-grade football players.

The bigger boys began the usual routine of shoving him into lockers and knocking his books out of his arms, but Kozarevich surrounded himself with friends who backed him up.

He eventually transferred to Alex W. Spence Talented/Gifted Academy, where he met dance teacher Lisa Moya King.

She took him under her wing right away. She moved to Woodrow, and Kozarevich auditioned for Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. Though he was accepted, he turned it down because he decided not to go into dancing as a profession.

“I didn’t want to go through what had happened earlier on because I was still a little naive about that, and I was also shy,” he says.

Instead he enrolled at Woodrow, which once again put him under the tutelage of King.

During his freshman year, while he was still fending off bullies at school, Kozarevich’s mom, Sue, was diagnosed with stage-four breast cancer.

“It scared me because I didn’t know what was going to happen,” he says. “That’s the most vulnerable you can be. Freshman year, I was starting to get back some of my self esteem, and then it just hit me like that.”

His other mom, Nancy, quit her job to take care of Sue, and Kozarevich started missing school days in order to spend time with them. At first, his grades suffered, but he worked with teachers and managed to complete the semester with all his credits.

Doctors determined that Sue was going to be OK, but about two months later she was diagnosed with skin cancer. They caught it before it spread.

During Kozarevich’s junior year, his mom’s breast cancer returned in the same spot as before.

“That’s when I started talking with Ms. King more about my personal stuff, and she helped me get through it,” he says.

Sue just recently found another lump, but the Kozarevich family is still waiting for the results. This time, they’re confident they will get through it together, just like they have every other time, Kozarevich says.

“It has helped being a dancer, because I feel free. I feel in control when I’m dancing. When I’m dancing on a stage, that’s when I feel the most in control and the most vulnerable.”

King has been working with Kozarevich on developing his leadership abilities. She’s also helping him learn to balance caring and compassion for things that matter and not caring about the things that don’t.

“A lot of the other boys were looking up to him,” King says, “but he didn’t see himself as a leader. I had to really push him hard to see himself that way. I think it kind of scared him at times.”

Her efforts paid off, and it helped Kozarevich change the way he interacted with his peers at school.

“Now, when I see someone get bullied in the hallways, I’ll be the first person to stick up for them, because it’s not fair that some people end up committing suicide because there was no one to help them,” Kozarevich says.

“I feel like I can make a change and overcome the stereotype of getting bullied.”

But more than anything, King’s class gives him the outlet to express himself.

“He wasn’t afraid to try anything with dance,” King says, “which comes from his upbringing. In dance, he’s very open. He doesn’t hesitate to get out there and try something.”

Even though he didn’t enjoy the visibility that Booker T. students have, Kozarevich was recognized by the Dallas Black Dance Theater, and he began dancing with the Allegra Ensemble.

He also has been accepted into Steven F. Austin and Texas State, where he plans to continue with dance as well as pursue a veterinary career.

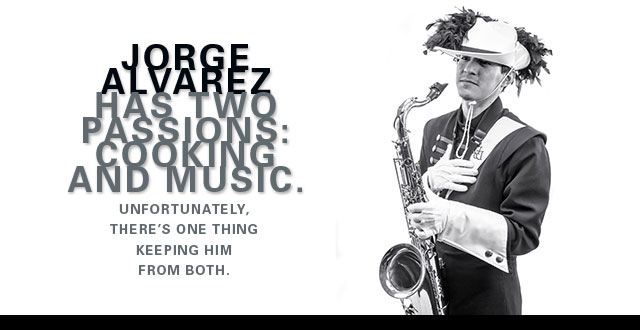

Woodrow Wilson High School senior Alvarez says, “It always comes down to money.” But, one way or another, he’s determined to pursue his dreams when he graduates in May.

Alvarez received his love of cooking from his dad, Jose, who was the chef at Celebrity Café & Bakery before he died of cancer in 2009.

Cooking is a family business, and Alvarez is a firm believer in tradition and family legacy. Growing up, his family seemed to enjoy cooking together so much, it fostered a dream in Alvarez to someday become a chef like his father and grandfather.

“I want to make my dad proud,” he explains.

But money is tight for Alvarez’s mom, so she won’t be able to send Alvarez to culinary school. He would never ask her to, anyway.

His other passion, music, began while he was watching a jazz band on TV. Something about the sax player gripped him, and he was hooked. From that moment he knew he wanted to learn to play.

Alvarez began playing saxophone in sixth-grade. Eventually he ended up in the band at Woodrow, which continued to encourage his love of music. It also became a training ground to cultivate his natural leadership skills.

Band Director Chris Evetts made him one of two drum majors and even awarded him a “best leadership” plaque at last year’s band banquet.

“I chose Jorge for that, easily,” Evetts says. “It’s in his nature to be very adult-like; it’s who he is. He impressed me right away because he was the only kid who would come up and ask me, ‘What needs to be done?’ ”

Band rehearsals and performances take a lot of preparation, Evetts says. Alvarez took the initiative to help load and unload equipment. He even recruited other students to assist, which soon boosted him into the position of loading captain.

When the time came for Evetts to find drum majors, he encouraged Alvarez to audition.

“It was exactly as I expected: He was very good at leading the other kids,” Evetts says.

Alvarez also worked hard at fundraising by selling chocolate bars in order to pay for private lessons, camps, trips and other expenses. He sold 20 boxes — far more than any other student sold.

A band scholarship would be a game-changer for Alvarez. Culinary schools don’t have bands, but Alvarez also is considering a career in music education if he can earn a scholarship.

Recently, Alvarez landed a job at Chipotle in order to save for a car. He hopes it will help him dip his toe into the food industry. Chipotle’s business model of promoting from within and helping qualified employees with their education piqued Alvarez’s interest.

“It’s a step toward the future,” he says.

He also happens to enjoy working there, he says, and has already received recognition for his hard work and determination from higher-ups at the location.

“I’ve got other seniors who don’t even seem to be aware that they should have been looking at colleges. Jorge has already started earning his own money for college,” Evetts says.

“That just speaks to the kind of determination he’s got, that he’s not going to let himself lose. He’s going to graduate, and he’s going to be ready.”

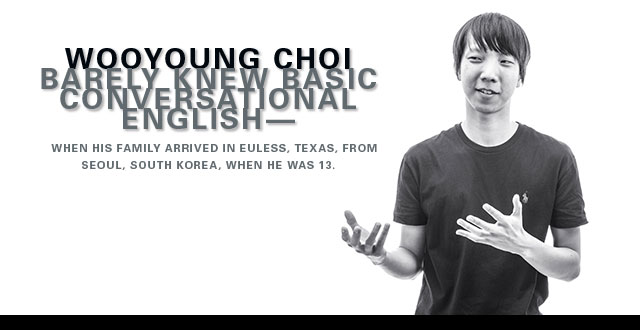

Choi was almost as fresh when he moved to East Dallas less than a year later.

He started attending J.L. Long Middle School, where he took ESL classes to help him get a grip on the language, but he was struggling.

“I knew a little about how to talk to people, but I didn’t know how to read or write in English,” he says.

He finished the ESL course in a year, and although he felt he still needed it, his teacher encouraged him to attend regular classes at Woodrow Wilson High School in order to learn more.

“That has been hard,” he admits.

At first, he felt isolated from his peers because of language barriers, and some students even picked on him. Although there were other Asian-American students, none of them spoke Korean.

“I didn’t really have anyone to talk with about my life, so that was stressful,” he says.

He couldn’t visit his friends or family in South Korea because of the terms of his visa, but by 10th-grade, he had the confidence he needed to make friends who helped him understand things about American culture, such as sarcasm, slang and jokes.

He continued to go to tutoring after class, but he’s still slow at reading and writing in English, which is a significant disadvantage to him in his International Baccalaureate (IB) classes.

IB, one of the four academies offered at Woodrow, is known for being workload intensive, but that’s the academy his middle school friends joined, so Choi followed suit.

He did well in the freshman and sophomore pre-IB and AP classes, and he even managed to excel in his junior year of IB classes.

“Junior year I thought, ‘I can do this,’ ” he recalls. “When I got to my senior year, the [classroom] strategy changed.”

He had to do more reading in his history class than he could keep up with, and some of the classroom exercises in English were beyond his capability — particularly the timed analysis of poetry.

He ended up dropping out of IB English and history, but he stayed in IB biology because he enjoys it. Despite the challenges, Choi will graduate in May with a GPA he can be proud of.

Susan Odeski, a college and career advisor at Woodrow, considers Choi “a student of outstanding character and high goals.”

He’s already been accepted to several universities, including UT Dallas. He wants to study biology, or something related to science, so he can eventually go to medical school and become a doctor, he says.