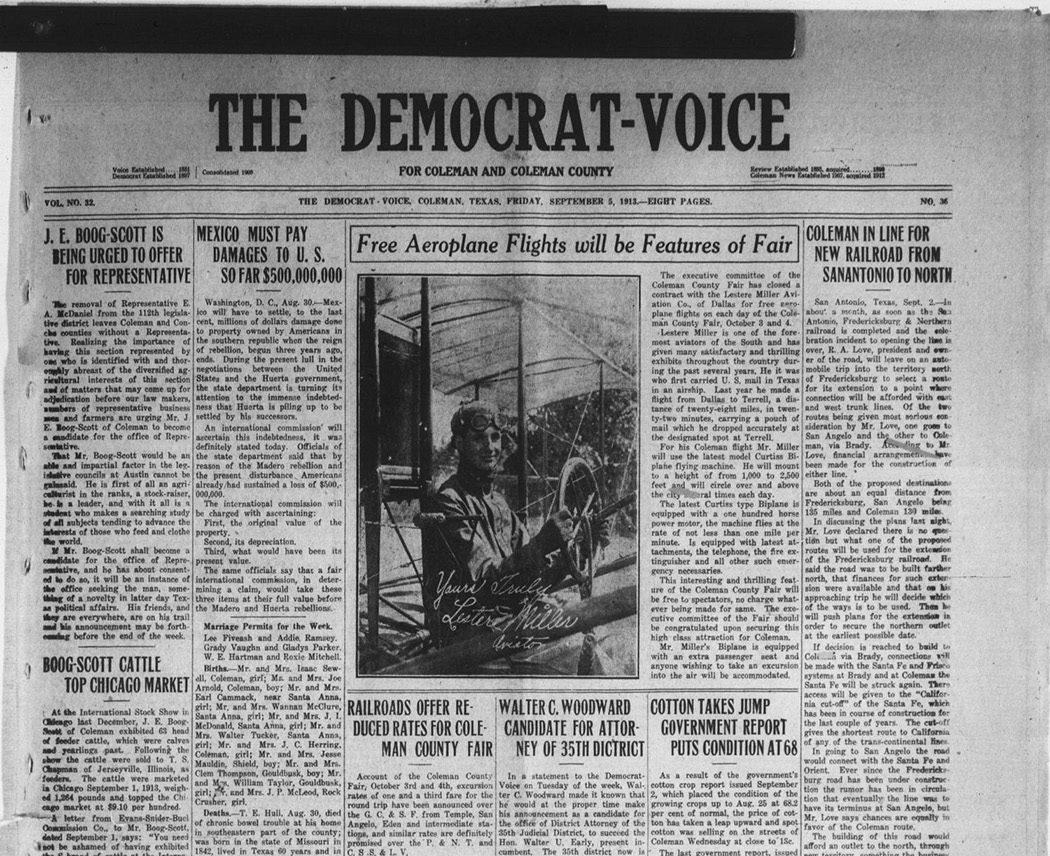

Lestere Miller, left, sits atop an early airplane model. Photo courtesy of the Dallas Public Library.

If aviation pioneer Lestere Miller bought a packing crate and put wings on it, his students at the Texas School of Aviation knew he could make it fly.

Perhaps no man in Texas did more to train the next generation of pilots and kindle curiosity in aviation than Lestere. In 1914, the Lakewood Hills neighbor opened the state’s first flying school on Columbia Avenue behind what is now Juliette Fowler Communities. In a large frame building that served as his hangar and workshop, students from across the state arrived to take lessons from the “Daring Birdman of Dallas.”

Lestere became a household name in 1911 when he departed Hillsboro and piloted the first recorded airplane flight in Texas. His fame continued to grow as he made the state’s first airmail flight from Dallas to Fort Worth on Jan. 8, 1917.

He took off from a pasture near the Lakewood Country Club and soared into the western sky over a crowd of cheering onlookers. Thirty-seven minutes later, he arrived in Fort Worth and made the return trip in 21 minutes thanks to a strong tailwind.

“He didn’t have a thought for anything other than aviation after the Wright brothers made their flight in Kitty Hawk,” his wife, Ione Miller, says in a 1973 interview. “He lived and breathed aviation all his life.”

Lestere was devoted to aviation, but he had little money for flight school, Ione says. He lived on 15 cents a day — enough to purchase bread and greens — as he taught himself to be a pilot and flight mechanic.

In 1912, he was awarded the 63rd pilot’s license in the United States. They number more than 600,000 today.

A year later, on Oct. 13, 1913, he got his airmail permit. Believing 13 was his new lucky number, he added an “e” to the end of Lester so his first and last name would total 13 letters.

In the early days of flight, airplanes did not have enclosed cockpits. Pilots, wearing layers of wool clothing for warmth, simply sat at the front of an exposed, triangular base to steer the aircraft. It was a dangerous hobby, and newspapers reported that Lestere’s plane crashed into several cars and fences.

During one flight, a crash landing pinned Lestere to the ground, and hot water from the radiator poured onto his back. A 12-year-old girl passing through the field where he landed was able to lift the plane so Lestere could crawl out. But he bore scars from the blisters on his back until he died. When people asked how he got the scars, he told them he was a lion tamer.

At the start of World War I, Lestere was drafted and sent to Dayton, Ohio. The daredevil pilot had a romantic streak, and a few months later, he and Ione married after a four-year courtship. The papers heralded the news with the headline, “Romance in the air.”

“I thought I’d rather be left his wife than his sweetheart,” Ione says.

But Lestere never traveled overseas to fight at the front lines. Instead, he trained pilots in Dayton before moving to New Jersey to manufacture planes for the Standard Aircraft Corporation. While working in the States, he kept his draft card in his pocket at all times to prove to angry passersby that he was still serving his country.

After the armistice, Lestere bought a shop in Dayton and used the materials to make planes that sold for more than $3,000. Lestere also built one of the first planes with a passenger seat and traveled throughout Texas and Oklahoma giving rides and performing demonstrations. His plane couldn’t fly to each destination because of its small motor, so Lestere had to disassemble the machine, ship it and set it up again for each exposition.

The demonstrations required just the right flying weather — clear skies and low wind. During an exhibition in Hillsboro, the pilot told the crowd the wind was too strong and canceled the flight. The angry mob claimed he was a fake and locked him in the local jail until city officials released him.

“He enjoyed telling that story as much as he could tell anything,” Ione says.

Lestere survived the dangers of flying — and entertaining its fans — but died from emphysema in 1963, despite the fact that he didn’t smoke. Even as he took his last breath, Ione says he couldn’t help but talk about his passion.

“I’m very proud of his contribution to aviation,” Ione says. “He was very interested in the boys going to the moon. If he had been a young man, he probably would have wanted to go there, too.”