Vision is good. The money to make it happen is better.

During his impassioned plea for us to put aside our sectarian differences and unite to build the Trinity toll road, Mayor Rawlings said, “Dallas has never been held back from a vision if we really set our mind to it.”

Which strikes me as the perfect nickname for Rawlings: Mayor Vision. He can see the future so clearly, and what he sees is so impressive — landmark parks and signature bridges and racial and ethnic diversity in the kind of city that gets featured in glossy, high-end travel magazines. The problem with that, of course, is that he spends so much time looking into the future that his grasp of the present seems shaky, even on good days.

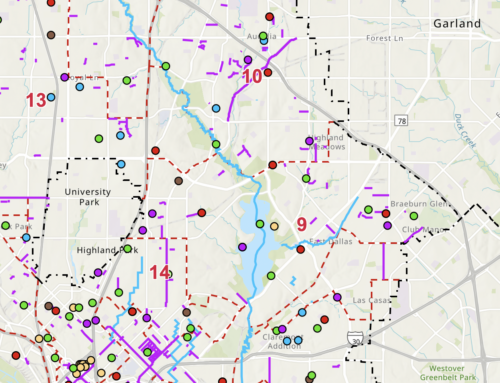

Consider, for instance, the pitiful state of so many of Dallas’ streets. How do we know it’s bad (and not just whining from a bunch of malcontents like me)? We actually have someone Downtown admitting it — the city manager says some $200 million to the November bond package will be used for street repair, twice what was originally planned.

My current favorite (and it’s not like I didn’t have a lot to choose from, including Forest Lane on the other side of the tollway, which is more third-world than world-class) is the intersection of Northwest Highway and Shady Brook, near Half Price Books. The best way to describe it is to paraphrase Tennyson: “Into the Valley of Death drove the six hundred …”

Seriously. Shady Brook south of Northwest Highway is higher than Northwest Highway, which means you’re driving down into a steep dip, either making a left or going straight. It has been that way for as long as I can remember, and that part of the intersection is potted and scarred with years of neglect, bad patch jobs and the like.

That’s bad enough. But what really makes the intersection dangerous is that drivers need to slow down to negotiate the Valley of Death. If they don’t, they’ll scrape the bottom of the car or bounce around or be forced to veer into oncoming traffic to miss a chuckhole. The catch, of course, is that Dallas drivers don’t like to slow down, and paying attention isn’t our strong suit, either. At the least, drivers have to pick their way through the intersection so slowly that only a couple or three cars can make it through at a time, especially when turning left, and traffic backs up on Shady Brook. Where, complicating matters more, there are cars trying to pull out of apartment parking lots. At the worst, there is a multi-car pileup waiting to happen.

So why hasn’t this been fixed? It doesn’t take vision to see what needs to be done and to see how dangerous the intersection is. But vision is cheap, and actually doing something isn’t. It doesn’t cost one penny to say, as Rawlings did in his speech, that “we must be one city rather than two. We’ve had North Dallas, and we’ve had the southern sector. Until we think and act as one city, we will not maximize our potential.” Those are grand words, and most of us want to applaud when we hear them — and we desperately want to believe them.

But Rawlings doesn’t have to pay for them, which is one reason why it is so easy for him to see so clearly into the future. What’s more difficult, and what the bosses Downtown have not been able to do for a decade, is to pay for our future. They’ve mortgaged it for their baubles and pretty doodads, and Northwest Highway and Forest Lane and hundreds — even thousands — of other problems are the result.

Yes, I want to live in a city where visitors stand slackjawed at what they see, but I know — as they know in the world’s great cities — that we can’t get there until we fix the present. Because, no matter how pretty Rawlings’ vision is, it’s a fantasy built on fiction, and reality will always intrude.