Dixon Branch Creek is a small, quiet creek surrounded by trees. It flows through some of our neighborhoods into White Rock Lake. Runners, dog walkers and serenity seekers utilize its greenbelts daily.

Dixon Branch’s peaceful scene is ironic considering the controversy that has developed over plans to prevent the creek from flooding. The controversy has pitted neighbor against neighbor and neighborhoods against the City.

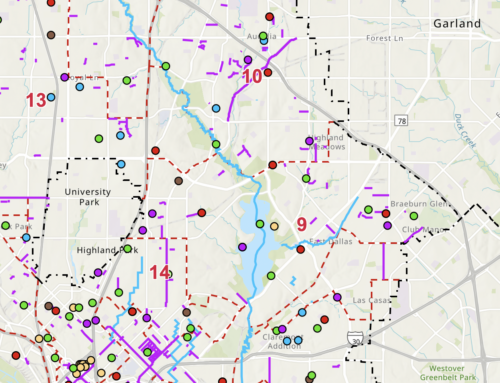

The City is planning a channelization project that will stretch from Buckner to Easton between Lake Highlands Drive and Creekmere, widening the creek to stop flooding in the area.

City officials and engineers say the project will address the flooding problem while protecting the creek’s environmental integrity. The project is estimated to cost $6.5 million, and City officials hope to fund the plan as part of a City bond election next year.

But some neighborhood residents oppose the channelization project and are rallying to fight it every step of the way. These opponents say channelization will destroy a neighborhood resource and take away the natural beauty of the creek.

“It’s a tough balance,” says Councilman Glenn Box, whose district includes the Dixon Branch Creek area.

“I’m not for putting in cement, but I am for protecting the citizens who are being flooded.”

Box supports the channelization project. One of his campaign promises was to do something about the flooding in the area, which has been a problem for several years, he says.

“I’m for saving the trees and saving the people,” Box says. “I think we can work out something that can do both.”

Channelization opponents say they want something to stop the flooding while leaving the creek’s beauty intact.

“We’re not going to let you destroy an established urban greenbelt,” says Gary Gene Olp, president of the Dixon Branch Preservation Group, an organization working to stop the channelization project.

“Why destroy it? Our City has too much concrete anyway.”

“In my lifetime, I will never see that creek that way again. Leave the creek alone. Let it be natural.”

Last fall, Olp noticed workers surveying and tagging trees along the creek. He called the City and found out about the project.

“It was soon obvious to me we were going to lose this greenbelt,” Olp says. “It will be a devastating loss.”

Since then, Olp and other neighborhood residents have been scrambling to fight the project. Another resident helping out is Jim Costello.

“We don’t know much about the City and how it works,” Costello says. “This has just been thrust upon us.”

Costello sent out 94 letters to neighborhood residents discussing the channelization project. He received 20 back, 14 against and six in favor.

He also made a presentation to the Sierra Club about the plan. The club passed a resolution opposing the project.

Costello says he and other neighbors are circulating petitions and trying to convince Council members not to support the project.

“The bottom line is we think it’s not acceptable, and the City needs to come up with a better design,” Costello says.

Olp says he understands the flooding problem needs to be addressed, but he says the City needs to find another alternative.

“It may cost more, but what the neighborhood will tell the City is what you’re getting ready to destroy you can’t put a price tag on,” Olp says.

“We bought (homes) here because of the trees that are here and the greenbelts that are all around. You strip that out of here, and all of a sudden you’ve stripped out the character of the neighborhood.”

“It’s going to take a fight,” Olp says. “We’ve got to make enough noise. We’ve got to let the City know: ‘Look, we live here and no one supports the plan.’”

Rod Zielke, an engineering consultant with Lichliter, Jameson & Associates, Inc., the company hired by the City to develop the plan, says the neighborhood opposition only developed recently.

Zielke says his company and the City worked closely with those neighborhood residents whose houses were flooded to develop a plan that would not destroy the creek’s beauty but would address the flooding problem.

In 1992, 617 questionnaires were sent to area homeowners regarding flooding on the creek and how it impacted the neighborhood and individual households.

The City received 293 questionnaires back, Zielke says, and the input from these questionnaires was used to develop the existing plan.

“We did recognize immediately the environmental concerns of the area,” Zielke says.

The group studied several alternatives, and in 1993, at a public meeting with about 60 residents, the plans were discussed. Zielke says with input from the residents who attended the meeting, the group decided channelization would be the best.

“There was an interactive process,” Zielke says. “We came away with positive feelings.”

Zielke says the group even rejected initial plans for hike-and-bike trails and picnic tables along the creek because residents didn’t want them.

The City’s plan calls for widening and deepening the creek in areas and creating a cement, faux-limestone bottom and bank to prevent further erosion. Some trees will be lost, but the City has gone to great measures to protect the trees, Zielke says.

Each tree in the area has been numbered and cataloged so that the plan can be developed to avoid as many trees as possible. Only a small fraction of the tagged trees will be destroyed, Zielke says, estimating that about seven acres of shaded tree area will be lost.

To stop creek-bank erosion, Zielke says the City will use gabion blankets covered in dirt and plants. The blankets are rocks that will be covered in chicken wire to hold the ground in place. By the time the structure is covered with plants, Zielke says it won’t be visible.

In some parts of the plan, Zielke says the City proposes to put a four-foot-high chain link fence where the bank is extremely high and dangerous. But Zielke says the fence was added for safety and will be thrown out if the neighbors don’t want it.

At the intersection of Lake Highlands Drive and Buckner, one soccer field will be lost due to the channelization project. But Zielke says the other fields at the intersection will be raised to prevent flooding, allowing increased usage of the fields.

Zielke’s company has been granted a contract with the City to develop construction plans. When the plans are complete, they will be presented to the neighborhoods. Zielke says he welcomes input for the plans.

David Dybala, assistant director of the Public Works Department, says it’s hard to convince some neighborhood residents that the natural beauty of the creek will stay intact because the City has never carried out a channelization project like this one.

In the past, channelization projects have torn down trees and plants, leaving nothing but a cement ditch. Dybala says the City does not want to do that with this project, and for the first time has gone to great lengths to preserve the environment.

Charles Lawrence, a neighborhood resident who supports the plan, says the biggest obstacle is getting residents to trust the City. Lawrence says he has been trying to combat rumors that are flying about the project.

“I’ve become real disillusioned and frustrated,” Lawrence says. “I’m convinced that at sometime in the future, if this plan is not done, that there will be a catastrophic flood and wipe out 60 to 70 homes.”

Lawrence began lobbying the City four years ago to have something done about the flooding. He has been flooded out of his home on Vinemont three times in 12 years. Each time, it ruined carpet, paint, furniture and Sheetrock.

He and other neighbors created East of the Lake Neighbors United Against Flooding. They worked with the City to find a solution and thought they had found it with the channelization until opposition arose a few months ago.

“It’s a real problem and for people like us who have flooded, it’s frustrating,” Lawrence says. “There’s a large group of people who want the problem fixed. We’re convinced that the best solution is a channelization project that will address the problem.”

For More Information About the Project call:

- Henry Nguyen with the Public Works Department at 948-4039.

- Elinor Seeley with the Dixon Branch Creek Preservation Group at 328-6639.