Chris Skoog, left, and Sally Freedman pose for a portrait in their East Dallas Home. The couple adopted their first dog together, Mac, when he was found at a gated entrance of Machu Picchu with a life-threatening cut on his paw. (Photo by Rasy Ran)

Three legs and two countries

It began as the trip of a lifetime to Machu Picchu but it became a rescue mission. Planes, train and automobiles all played a role. Pachamama, the Andean goddess, helped out, too.

It was October 2016, and neighbors Sally Freedman and Chris Skoog were at long last at the ancient Inca city in the Andes mountains of Peru, a destination high on their travel bucket list.

They hiked the rocky terrain for eight days, with Machu Picchu as the planned culmination. As oft-annoying fate would have it, though, the morning after their arrival at the site, Skoog developed a serious bacterial infection. Freedman was headed to the small mountain infirmary for medication when she happened upon a grievously injured dog.

Attitudes toward dogs in North versus South America are quite different. They love their dogs, yes, but most are not allowed indoors, nor are they routinely spayed or neutered. The result is a huge stray dog population.

Freedman and Skoog, lifelong animal lovers, were aware of this and vowed to help every stray they could by doling out the kibble they carried in their backpacks.

When Freedman happened upon the injured dog, she naturally offered him some food. “He didn’t budge,” she recalls, “and I asked him what was wrong.”

As though understanding, the dog managed to stand up and held out his right leg to show her. The paw had been cut off and bone was exposed.

The infirmary doctor told Freedman that the dog — later dubbed “Mac” in a nod to Machu Picchu — had been carried up the mountain the day before by someone who found him near train tracks. He was streaked with grease, and seemingly had been struck by the train. Due to limited resources, all the doctor could offer him was pain medication and a bandage, the latter of which he gnawed off in short order.

The doctor told the head guard at Machu Picchu Park that Mac needed to get to a veterinarian in Cuzco, hours away by bus, train and car. But the buses wouldn’t be swayed from their “no dogs” rule.

Enter Freedman and Skoog who, after hearing of the obstacles, were on a mission. A bedridden Skoog, barely conscious and in need of IV fluids, urged Freedman to do all she could for the dog. Freedman remembers, “I marched up to that head guard and, in my worst Spanish, cried to him that we needed to help ‘el perro sin pata [the dog without a paw].’”

With the guard’s permission, Freedman then approached the bus chief. By this time, several park guards had become Freedman’s cheering section and accompanied her for the conversation. The bus chief remained stubborn in his “no dogs” rule until, out of frustration, Freedman insisted, “Pachamama wants you to do this!”

Invoking the name of this revered goddess from Inca mythology, a Mother Nature-type figure, did the trick. The bus chief relented immediately.

Word had spread about the “gringa trying to help the dog.” It inspired local guide Jimmy Vasquez-Calderon to get busy making calls. “I told Sally I would try to help, but I honestly had no idea what I was going to do,” he says.

Vasquez-Calderon had connections on the bus and train systems. Says Skoog, “A key person in this equation was Jimmy. He knew the local resources and was able to get them to help us.”

The guide would accompany Mac to the town of Ollantaytambo where, again through Vasquez-Calderon’s connections, a veterinarian met them and took the dog the rest of the journey to Cuzco for continued care and surgery.

Sadly, amputation of much of Mac’s leg was necessary. While he recovered, Freedman and Skoog began the search for an adoptive family. But the dog’s warm response to them when they visited him at the vet’s office sealed their fate: Mac was their dog.

The couple returned to Dallas while Mac stayed with Vasquez-Calderon and his wife and children to complete his recovery and 30-day vaccination/incubation period before he could switch countries. When Freedman returned to Peru to get Mac, the Vasquez-Calderon family had mixed emotions.

“The whole family was involved [with Mac’s care]. We all did it with so much love, and it was very hard to see Mac leaving with Sally. It was a very sad moment for all of us,” he says.

Back in East Dallas, Mac adjusted remarkably well. He received special training and learned to thrive on his three legs. Because he tires easily, he takes two or three short walks each day and is well-known on his Belmont Avenue block. He is gentle with the next-door neighbor’s baby, submits happily to petting from another neighbor during each evening stroll and romps in his yard with his beloved Buc-ee toy.

Skoog admires Mac’s sweet, easygoing “disposition around people and animals alike: It makes him the star of everyone’s day.”

He is so beloved by the couple that Mac will play a role in their wedding this October.

“The look he gives me when I rub his belly or console him is so full of love,” Freeman says. “I just see how much he loves being part of the family.”

Patti Vinson is a guest writer who has lived in East Dallas for over 15 years. She’s written for the Advocate and Real Simple magazine, and has taught college writing.

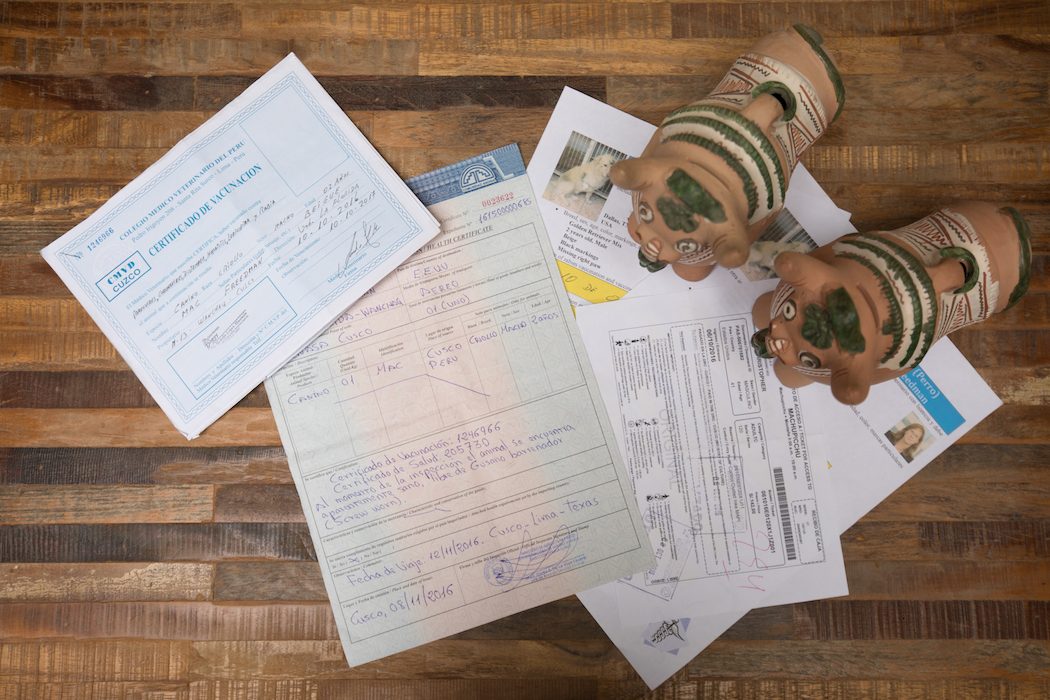

Paperwork detailing Mac’s medical and adoption process from Peru to the United States. (Photo by Rasy Ran)