It’s a question as old as the act itself.

The lights come on at Lakewood Theater, and burlesque dancer “Lillith Grey” takes the stage like a thunderstorm. Her audience is enraptured, every eye trained on the layers of her candy-green garments as she expertly twirls and occasionally flicks the fabric aside to expose various levels of undress underneath. Boisterous music blares from the loudspeakers while Grey saucily stomps around the front of the stage to the beat of the tune, sucking on a fake cigarette and gesturing to the audience for feedback, which they immediately answer with whoops, cheers and whistles. In a moment of exaggerated mischief, Grey sashays off the stage and — with a wink and a smile — helps herself to a long swig from the beer of an unsuspecting audience member. The crowd rewards her antics with hoots of raucous laughter, and then the music transitions, and Grey finishes her act to the lazy tune of “Ganja Babe” by Michael Franti. “Ganja babe, my sweet ganja babe, I love the way you love me and the way you misbehavin’,” Franti sings as Grey seductively unwinds, slowly losing her costume, piece by glittery piece.

There’s no denying there’s power in sex. It permeates our music, packs our movie theaters, lines our bookshelves, and sells everything from toothpaste to beer to cars. The media is rife with it — both using sex and defining what is and is not “sexy.” Everywhere that there’s sex appeal, which is basically everywhere, a question seems to follow closely at its stiletto-clad heels: Who holds the power of sex — the provider or the consumer?

Burlesque in particular, which is a form of underground entertainment that has gained increasing momentum in the past decade, seems to flirt with the line between sexual vulnerability and sexual empowerment. Right now, Dallas is leading in the world of burlesque, and Lakewood’s own Viva Dallas Burlesque, where performers such as Grey entertain guests on the first and third Friday of every month, is one of the biggest shows in the nation.

There are a lot of misconceptions when it comes to burlesque, says Shoshana Portnoy, the founder and producer of Viva Dallas Burlesque. “I think the word is scarier than it actually is,” she explains. Those who’ve been around Dallas for a while know that Dallas is no stranger to the burlesque scene, but burlesque disappeared for a while, and now it has re-emerged with a whole new face. But to fully understand what burlesque is today, first you have to understand what it was.

The naughty nightclubs of yesteryear

Burlesque originated in Europe and then trickled over to the United States during the 19th century. It started as a satire, poking fun at popular plays that the upper class enjoyed and common folk couldn’t afford. At the time, burlesque was merely a sideshow; it didn’t start becoming the main attraction until the 1940s.

The 1950s were what many consider the pinnacle for burlesque in America, and Dallas was a leading force in the world of burlesque. Downtown Dallas was heavily populated with these nightclubs, and like most gentlemen’s clubs today, it was a male-dominated world. Big-name producers Abe and Barney Weinstein and their competitor Jack Ruby, who later became infamous for shooting Lee Harvey Oswald, were the kings of burlesque. The Weinsteins and Ruby allegedly were involved in rival mob groups, and they made a killing off of beautiful women with big hips and tiny waists baring all — or, at least, almost all. At the time stripping everything off was illegal. The barest a woman could get was pasties and a G-string, but even that was somewhat rare. Even though burlesque was considered a questionable business, talented striptease artists were A-list celebrities. Stories about Candy Barr, the most famous dancer in Texas, or national stripper Lili St. Cyr, often appeared in the gossip columns of the tabloids, and like today’s celebrities, they endorsed makeup brands or showcased the latest fashion trends on the glossy pages of glamour magazines.

By the ’60s, the shows were growing raunchier and raunchier in order to compete with television and the general rise of the modern-day sex culture. In the ’70s, burlesque lost the limelight to bare-all gentlemen’s clubs and HBO. For more than two decades, burlesque became a thing of the past.

Rediscovering the art of tease

Within the last 15 years, burlesque has re-emerged with the renewal of America’s seeming fascination with all things retro, but this time around burlesque ain’t your grandfather’s strip club.

These days, Dallas is once again leading, at third in the country for largest amount of burlesque audience members and performers. Lakewood’s Viva Dallas Burlesque brings in anywhere from 400 to 600 guests every other week, and usually 60 to 70 percent of those audience members are women. Yep, women.

So, what’s happening on the other side of that box office that’s drawing throngs of women to a show where woman after woman loses her apparel? The answer lies in the unofficial characteristics of today’s burlesque, called “neo-burlesque.” Though it offers a polite nod to the burlesque of old, neo-burlesque is a show entirely its own, differing from both the burlesque of yesterday and the strip clubs of today. It’s those differences that bring hundreds of women and their male counterparts through the doors, and it’s also the reason why burlesque performers insist that they, and not the audience, hold the power of sex.

Sex objects or sex goddesses?

Around 7:30 p.m., a line begins to form outside the Lakewood Theater to see Viva Dallas Burlesque’s production of “Dirty, Sexy, Funny,” and heading up the line is burlesque superfan Robert Hammer. “I think I’ve maybe missed one show since [Viva Dallas] started,” says Hammer, laughing.

To him, burlesque is the perfect storm of entertainment and sex appeal. “I enjoy performance art,” he explains. “This is real art involved, rather than a stripper on a stripper pole. A lot of people think it’s the same thing.” The biggest difference is that, for most performers, burlesque is a hobby and not a career, he says. “The performers get just as much a kick out of it as the audience.”

Not only is burlesque a hobby, but it can be a very expensive hobby, according to Portnoy. Most of the dancers are lucky to break even with what they make versus what they spend on costumes and props. Very few women (or men) make a living from burlesque, unlike the dancers of old, who often danced to survive.

“I genuinely enjoy performing,” says Michelle Mashburn, the production manager at Viva Dallas and the managing editor for Pin Curl magazine. “I’ve always said if it ever gets to the point where it stops being fun, then I’ll stop doing it.”

Mashburn says she’s always been intrigued with the power structure of burlesque.

“Some people think it’s not a good environment for women. They think it’s demeaning or demoralizing for women, but that couldn’t be further from the truth,” she insists.

Each performer is in complete control of her own routine, Mashburn says. No one tells the performer what to do. She brainstorms and orchestrates each part, deciding if it’ll be witty and upbeat, slow and sexual, or somewhere in between. The performer also determines how much clothing she will or will not take off, Mashburn points out. Also, burlesque performers are not working for tips, so no amount of extra skin is going to earn them extra cash.

“The giant difference between then and now is that it was very male-dominated and male-run, and now it’s female-dominated and female-run,” Portnoy explains. “There’s women making decisions now.”

Women empowering women

Today’s burlesque also holds one other key, differentiating factor close to its sequined heart. One commonality between yesteryear’s burlesque and today’s gentlemen’s clubs is the size and shape of the dancers: busty girls with thin waists, round hips and long legs. But not in neo-burlesque.

“We abide by the belief that all shapes and sizes are beautiful,” Mashburn says, “as long they’re entertaining.

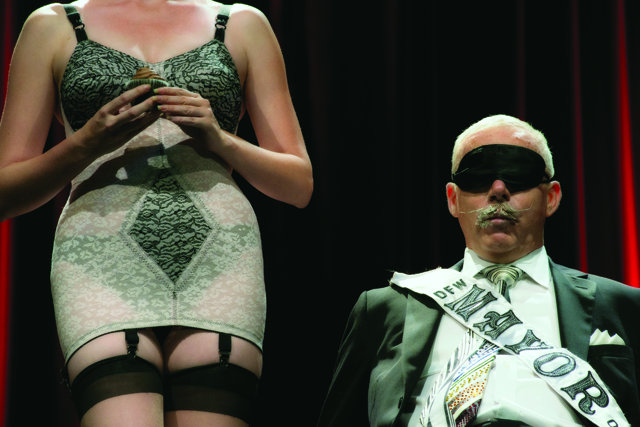

“Jerry Fedora” (not his real name) receives a birthday surprise during the show “Dirty, Sexy, Funny.” Danny Fulgencio.

“You’re almost completely naked on stage, so of course there’s a level of vulnerability,” Mashburn says. But some performers say the beauty of burlesque is that it teaches women to embrace sexual vulnerability and train it into sexual empowerment. In turn, the performers help the audience members embrace their own sexuality.

“We don’t want anyone to leave feeling less pretty than when they walked in,” Portnoy explains. “Whatever your body flaw or insecurity is, there is someone on the stage who has that same thing.”

So, who holds the power of sex?

The stage lights fade out, and the house lights come on as audience members begin to pack up their belongings and clean up their trash. It’s well past 10:30 p.m. by the time lines of people begin filing out the doors of the theater. In the hallway, some of the performers have booths set up to sell handmade take-aways, such as pasties, boas and mini top hats. The rest of the performers stand around chatting with any audience members who care to meet them, snap a photo or get their autograph.

“Ursula Undress,” who traveled from Atlanta to be the headliner for the night, is particularly popular among lingering audience members. She was easily one of the best performers of the night, not the least bit shy about showing off her big-girl curves.

“As a performer, I do feel powerful,” she says. But the performance is for the audience, so the audience does hold a certain amount of power over the performer, she says.

“The performance is like sex. You can’t do anything without each other,” she explains.

“The audience has its own power, because if nobody reacts then I feel pretty powerless on stage. But then at the same time, I have the power because I am telling them what they get to look at.”

It’s a balancing act, she says, between the provider and the consumer.

“I think, when it comes to power, each side holds it.”