Photography by Danny Fulgencio

When Willis Winters answered the unknown number on his phone, the last thing he expected was a frantic message from a Washington-based researcher pleading with him to save the light pole at Dealey Plaza.

The pole, located at the corner of Elm and Houston streets near the old Texas School Book Depository, had been hit by a car and was on its way to a salvage yard when the East Dallas neighbor with a penchant for history and preservation interceded.

Winters, the former director of the Park and Recreation Department, took it to the Boneyard, located at the IC Harris Service Center just a few minutes south of Samuell Grand Park. There, a team of researchers and FBI agents studied the role the light pole may have played in the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

When the study concluded, neither The Sixth Floor Museum nor the National Archives wanted the historic artifact. Since then, it’s remained in a shipping container at the Boneyard, where Winters has quietly stashed other pieces of the city’s past to save them from the wrecking ball.

The site is called the Boneyard, but the name is scarier than the actual location. It’s simply a dusty, slightly overgrown field filled with architectural relics sitting on wooden pallets at the back of the park maintenance facility. The items would be too expensive or time intensive to create today, so Winters saves them in case they can be reused for park projects or loaned to groups on behalf of the department.

The Boneyard started in the 1990s when the City of Dallas restored the Tenison Memorial Gates at Samuell Grand Park. Built in 1924, years of dirt accumulation and mortar deterioration had left the structures in poor condition. The column capitals were too dilapidated to save, so restoration workers molded and recast replacement pieces before giving the originals to Winters to take to the fledgling Boneyard.

Other pieces soon followed. Gold rings from a parking garage, stone parapets and fences torn down from community pools are littered throughout. There are even two rows of seats salvaged from the Cotton Bowl after bleacher seating was installed in 2009.

Not even Winters knows all the items stored at the Boneyard. With his retirement in October, the park department embarked on a mission to identify and label the artifacts scavenged from across the city.

P.C. Cobb Stadium

Concrete slabs featuring illustrations of athletes are all that remain of P.C. Cobb Stadium. The 1920s stadium was torn down to build the Infomart at Oak Lawn Avenue and Stemmons Freeway. Five stories in the air, demolition workers used a jackhammer to break the façade into pieces and lower them to the ground. They were stored in a warehouse for years until Winters brought them to the Boneyard. The goal is to use the slabs in a seating plaza at Stemmons Park where neighbors can peek into the world of high school athletics during the early 20th century.

Great National Life Insurance Company offices

The building that housed the Great National Life Insurance Company offices was built in 1963, but it had the look of the future. The innovative and revolutionary building at Harry Hines Boulevard and Mockingbird Lane was wrapped in aluminum sunshades that stretched along the façade — contrasting the flat, clean lines of office architecture in the 1950s. The building, which became the Salvation Army headquarters in the 1980s, was added to a Preservation Dallas list of most-endangered buildings. That didn’t save it from demolition in 2018. A portion of the diamond-shaped shades was taken to the Boneyard for possible reuse.

Titche-Goettinger cartouche

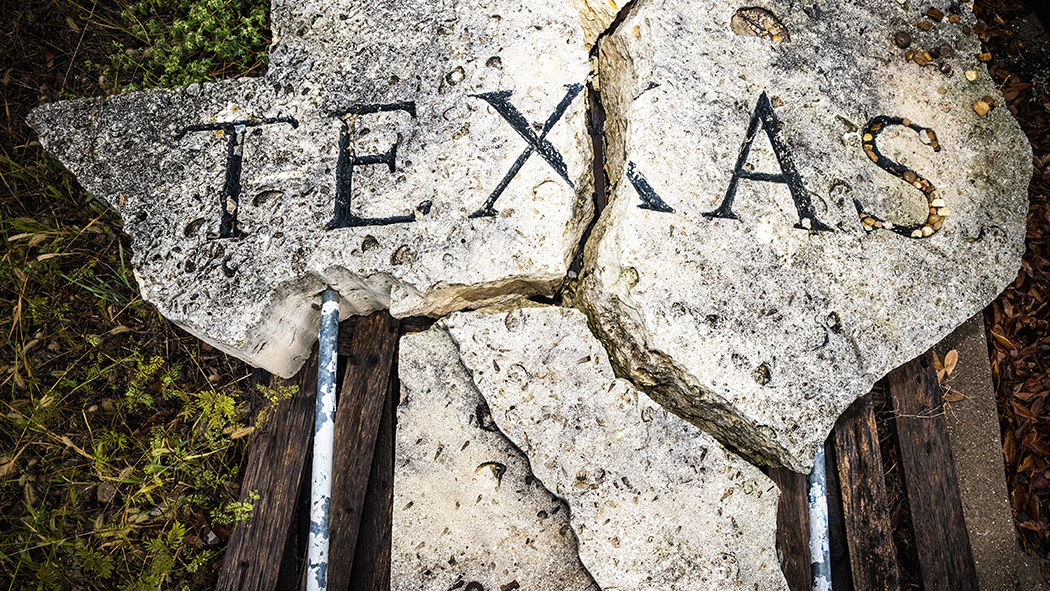

In 2012, a 96,000-pound cartouche that once adorned the Titche-Goettinger department store in downtown Dallas came to rest at the Boneyard. The crest depicts images of commerce and industry, as well as the six flags that flew over Texas. The limestone pieces were removed from what is now the University of North Texas chancellery to make way for new windows.

Fair Park fish fountain

You’ve probably seen the fish fountain that sits in front of the Women’s Building at Fair Park. But the 1936 original, designed by Raoul Josset and sculpted by José Martin, is tucked away in the Boneyard. After years of neglect, the half circle of flying fish was restored in 2000. The original is kept in storage in case restoration workers need to again mold and recast the crumbling cast-stone sculpture with a plaster coating.