From Petty to Profound, There’s A Story Behind Every Street Name.

Did you know Harold Abrams committed suicide after a tortuous battle with cancer?

Did you know Harold Abrams committed suicide after a tortuous battle with cancer?

Or that John M. Oram pocketed the City’s first driver’s license, which at the time cost 50 cents per year?

How about that Col. Jefferson Peak thought organ music was so sacrilegious, he left the church he helped found because of it. (He even took the minister along with him.)

Would you believe that Lovers Lane actually was named by “lovers?”

Most of us probably don’t give much thought to how the street we live on received its name.

But behind each name is a personality, a family and a story.

During a time when Dallas was little more than farms and fields, early settlers developed the land, building homes, businesses, churches and schools.

And more often than not, friends and relatives gave more than their sweat to help build our City – they gave their names, too.

As a result, we have streets named after doctors and daughters, lawyers and sons-in-law, bankers and mothers, cattle ranchers and wine connoisseurs, grandchildren and butchers, even a jewelry maker or two.

So, open up your City map, and ride along with us on this trip down Trivia Trail.

The Name Game

The closer they are to Downtown, the more likely it is that streets are named after historical figures, says Jim Anderson, a senior planner for the City’s Planning and Development Department.

Streets in more recently developed neighborhoods often don’t carry the links to our past that our neighborhood’s streets do.

For example, in North Dallas, an entire neighborhood honors the magical world of Disney with the street names Cinderella, Pinocchio, Peter Pan, Aladdin, Snow White and Dwarf Circle.

Developers are responsible for naming streets, which in a city of Dallas’ size can pose a challenging task today.

The City no longer allows a new street to be given a name that duplicates or even sounds like one assigned to an existing street.

Duplication can cause confusion for the fire and police departments, says Dwayne Taylor, who reviews new street names for the City.

Also street names can have no more than 14 characters, and if named after a person, that person must have been dead for two years, Taylor says.

But developers are creative, Taylor says.

In the White Rock Lake area, for example, there’s a Cimarec Street: For those who are Wheel-of-Fortune-challenged, that’s ceramic (as in kitchen or bathroom tile) spelled backward.

Taking A ‘Peak’ At History

Capt. Jefferson Peak, a farmer and merchant who served in the Mexican War, moved his family to Dallas from Kentucky in the 1850s. He fathered 12 children and died in 1885.

Peak developed his East Dallas farm – bounded by what today is Haskell, Carroll, Capitol and Elm – into a residential area and sold parcels to other settlers.

He named many of the streets after his sons, including Junius, a Civil War veteran who served as City marshal and as captain of the Texas Rangers; Worth, who worked in real estate; Carroll, Fort Worth’s first doctor; and Victor. Flora Street is named for one of Peak’s daughters, Florence.

A religious man, Peak helped found Dallas’ first Christian church; but he left soon after when John M. Oram, the first jeweler in Dallas (for whom Oram Street is named), donated an organ to the church.

According to history books, Peak believed instrumental music in church was disrespectful. Naturally, Oram didn’t agree.

So the two men broke into separate camps each Sunday, with the pro-organ parishioners sitting on one side of the new church and the anti-organ faction on the other.

Eventually, Peak and his followers, including the minister, left the church and held worship services at Field’s opera house, established by Peak’s son-in-law and Florence’s husband, Thomas W. Field, who also has a street named for him.

Later, the anti-organ group established the Commerce Street Christian Church, which became Central Christian Church.

Peak Street initially was named after Peak’s wife Martha, whom he married when she was 14 years old. After Peak died, Martha asked the City Council to rename the street in honor of her husband.

Daughter Sarah Ann Peak’s first fiancé died on his way from Kentucky to Dallas when his ship exploded; daughter Juliette’s infant daughter died at nine months old.

Later, Juliette’s husband, A.Y. Fowler, was stabbed in a fight and died from infections. Juliette was pregnant again at the time, but the child died soon after his first birthday.

Both Fowler and the man Sarah Anne eventually married, Alexander Harwood, have Dallas streets named after them.

Harwood, who lived with Sarah Ann at 4117 Swiss, was a county clerk and assistant postmaster of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Fowler was an up-and-coming lawyer from Fort Worth.

And Juliette never remarried; she died while establishing a home for orphans and the elderly. Today, Juliette Fowler Homes sits near Woodrow Wilson High School at 1234 Abrams.

What Is A Vickery?

Like many neighborhood streets, Vickery Boulevard was named by the man who developed the surrounding area, known as Vickery Place, located between Greenville and Central from Henderson to Vanderbilt.

George Works, who started Works-Coleman Land Co., named some of the streets in this area for co-workers, including Goodwin and Miller avenues.

The name Vickery was the maiden name of Works’ wife, Lillian. Her parents were from Fort Worth, and Vickery, Texas, is named for her family.

Today, George and Lillian’s grandchildren, George III and Nan Works, run the company their grandfather founded, renamed G.W. Works Real Estate. But the company is now solely involved with rental property management.

“Grandpop Works was still going to the office when I was a kid,” says George III. “He did a little something until he died (in the 1960s).”

Grandpop Works was also manager of the Dallas Street Railway Co. and worked to encourage a trolley line to come out to McMillan and end at Vickery Boulevard so he could bring people to his new development and show them houses, George III says.

Grandpop Works himself owned a house on Vickery Boulevard, where he raised his children, including his oldest son Richard, for whom Richard Street is named.

From Farmhouse to Schoolhouse

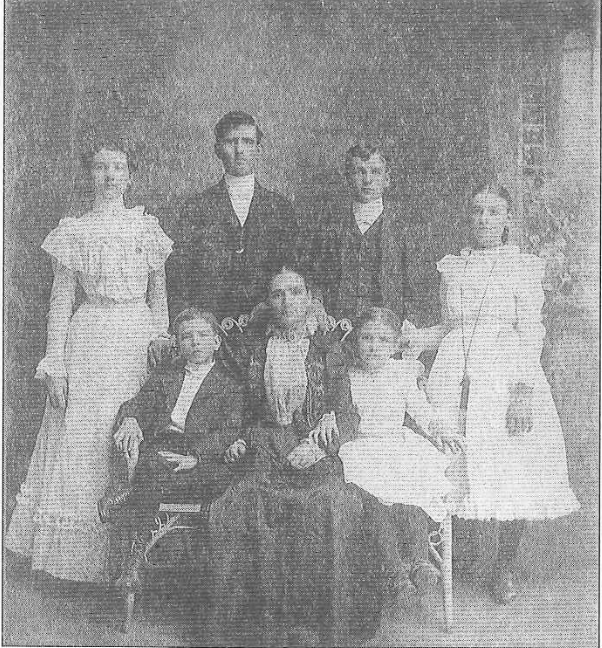

Anna Moser poses with her children (standing from left) Frieda, Charles, Otto and Tillie; (sitting) Ernest and Huldah. Huldah is Helen Hetherington’s mother.

Moser Avenue is a small street running between Ross and Capitol parallel to Henderson, but for Lakewood residents Helen Hetherington and Mary Louise Bosworth, this little street carries a big legacy.

Hetherington and Bosworth are first cousins and granddaughters of Christian and Anna Moser; for whom the street is named.

Hetherington, 78, tells of a time when the area surrounding Ross and Henderson was a dairy farm owned by her grandparents.

Her grandparents’ house once was located where the John F. Kennedy Learning Center site today at 1802 Moser next to Ross Avenue Baptist Church.

In this house, Grandma Anna (as Hetherington calls her) single-handedly ran the family farm and raised six children after her husband’s death at a young age.

After Grandma Anna’s sons and daughters were grown, they moved into houses nearby and raised large families themselves. They all returned to their childhood home Christmas Eve, however, for a hearty dinner and exchanging of gifts, Hetherington says.

Grandma Anna was a shrewd investor, Hetherington says. “She had little pieces of property all over Downtown.”

Grandma Anna financed the efforts of her oldest son, Charles Moser; to develop the dairy farm into residential lots. It was Charles (Hetherington’s uncle and Bosworth’s father) who gave Moser Avenue the family name. Charles also built homes in the area surrounding Stonewall Jackson Elementary School, Hetherington says.

When Hetherington was growing up, she says the Ross and Henderson area was a “very nice” neighborhood filled with beautiful homes.

Located nearby was St. Mary’s college (which closed in 1930), where Grandma Anna’s daughters attended school. The dairy was named College Hill Dairy because of its vicinity to St. Mary’s. There, the daughters met Bishop Alexander Charles Garrett, for whom Garrett Avenue is named. Garrett came to Dallas in 1873 to head the North Texas Episcopal diocese and opened St. Mary’s in 1889.

How would Grandma Anna feel if she knew her land is now occupied by a school bustling with children like her home once was during the Christmas holiday?

“My grandmother would feel good about that,” Hetherington says. “At least it didn’t turn into some grungy used car lot.”