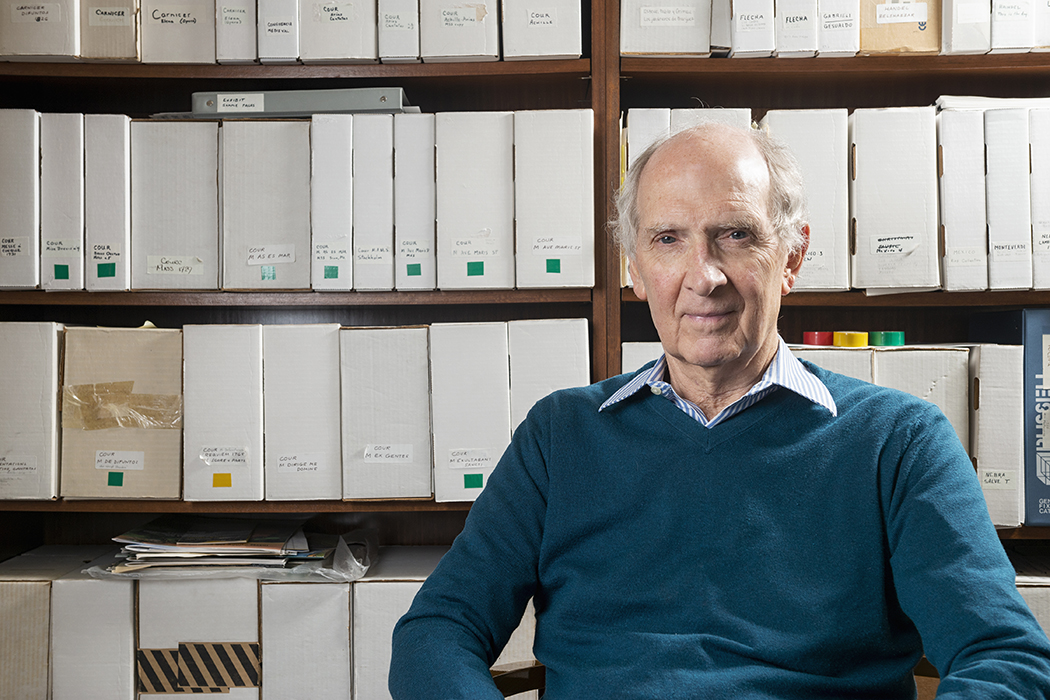

Grover Wilkins holds forth in his Central Expressway office and asks, “Do you know the Spanish equivalent of Bach, Vivaldi and Handel?” Music director and founder of the Orchestra of New Spain, Wilkins travels to Spain to research Baroque composers and bring their music back to modern audiences. While an archivist records his finds for musicians in a cramped room, Wilkins waxes poetic about the white dust and silica found on documents often not seen for generations. The neighbor estimates that his organization of more than 40 instrumentalists and singers has performed about 100 concerts in 30 years. A native of Lakewood, he graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School, Stetson University and the University of Michigan. Family genealogy reveals his relatives came from Dorset County, England, to Farmers Branch in 1742.

How did you become interested in Spanish Baroque music?

We live in a city that is more than half Hispanic. We have the Cathedral of Guadalupe. In the mid-1980s, I conducted a series there and went to the Dallas Museum of Art afterward. I looked down the street to the cathedral, and I thought, “I’m going to put on a concert of Spanish music there.” I didn’t say Mexican. I said Spanish. I wanted chorus and orchestra — splendor. We know German Baroque, Italian and French Baroque, but I couldn’t find anything that was Spanish. I thought, “This is an opportunity.” I met with Jane Holahan, who was head of arts at the Dallas Museum of Art. She said, “I’ve got a problem. It’s one year from the opening of the Meyerson. We don’t have an African-American event. We have nothing for the Hispanic community.” The symphony sent me to Spain six months before the opening of the Meyerson. I had been given a Fulbright to go to France and work on early 20th-century French film music.

What happened next?

I went to the Bibliothèque Nationale. Low and behold, I found 10 volumes from 1856 of the history of Spanish music. In it was a Baroque Requiem mass by a guy named José de Nebra of whom I had never heard. For the funeral of the Queen of Spain, it was from the 1750s. Next, I went to the Royal Palace, and there was a guy named Courcelle. It’s one of the best pieces that I’ve seen in the 30 years I’ve been doing this. It was featured in the first concert that we did in Dallas in the cathedral. I made a deal with the Dallas Symphony for a series of four concerts.

How do you achieve work-life balance?

Music is not work. The job here is running a nonprofit. I’m under the gun for all the money. The orchestra has prospered because we were a way for interested people to invest in Hispanic and Spanish culture. Not only are we succeeding here, but we’re having an impact elsewhere. Our first opera production was invited to go to Spain because nobody in Spain had produced a Baroque opera in the past 20 years. As we move into our fourth decade, I’ve started talking to recording companies and publishers.

How would you like to be remembered?

Nobody’s remembered unless you’ve done something heinous. Bringing to light Courcelle is an accomplishment. He’s not appreciated by the Spanish because he came from France through Italy. They changed his name because they couldn’t pronounce his French name, even though the king was French. He’s a significant creator of opera and liturgical music.

How do you help students?

We bring kids to concerts, and we perform at schools. We’ve gotten wonderful letters from teachers about what happens to kids who have these visitors from across the ocean — kids who’ve never been on an airplane. We’re bringing the shows, the residency, classes and summer strings camp. Those are the four biggies. During summer strings camp, we take them to the museum to see what visual art looks like there.

What do you regret?

I am disappointed in a lack of understanding of artistic and cultural context. One of the problems we face is that people don’t understand the difference between culture and art and the artisanal world. It’s hard for us to communicate sometimes because there’s such a gap. Dallas is not curious about music. For the last three years, I’ve been on a campaign to get the arts establishment to get the Dallas Independent School District to do better with the arts and with education.

What is your most challenging moment?

The most difficult thing that I’ve had to do was to produce our first opera in 2013 in the new, now Moody, concert hall. We didn’t have enough money, but we had to sign contracts. We had to audition people. We had to bring people in from Europe. My wife and I just inherited a little money, and I had a bit of money. The Latino/Hispanic community is mostly blue collar. And the blue collar in any culture, with the exception of the Viennese and maybe a few people in Berlin, don’t really cater to classical music. We’ve done some remarkable stuff. We’ve put on three operas, singing operas, and we’re doing another one next year. We’re able to do that, and we’re able to do it for a pittance.