Photography by Danny Fulgencio

Mark Painter is chatting with visitors while hoeing weeds at the Geneva Heights Elementary garden when he pauses, bends down, picks up a black plastic bag wrapped around an okra plant and frowns. “Look at this.”

This plastic, along with any other disregard for the environment, is a pet peeve of his. The beloved founder of the 20,000-square-foot garden at Mockingbird Elementary retired six years ago but has continued to quietly contribute to the neighborhood and protect the environment in a variety of ways.

In fact, he begins each day with a simple act: picking up trash as he walks his dog, Cosmos, a stray that was living under a portable at Mockingbird Elementary.

For the early morning strolls, he carries two plastic bags: one for Cosmos and one for random trash he sees littering the streets and alleys of his Lakewood Heights neighborhood. He easily fills a bag with small plastic pieces from car parts, cable wires, construction litter, electronics and some pieces he can’t identify.

“Plastic never goes away,” he says. “It just weathers into smaller particles. If I pass some on the street, I have no choice but to pick it up.”

He sees cardboard, Styrofoam, plastic film and bubble wrap, which is on the rise because of online shopping, and is frustrated.

“Much or most of it will end up in the ocean if it’s not collected and disposed of properly,” Painter says.

After these walks, he adds Cosmos’ contribution to his compost and the plastics to his recycling bin.

A couple days a week he heads over to Geneva Heights Elementary, where he tends to the burgeoning garden, hoeing the ever-present weeds, checking potatoes for bugs and keeping a watchful eye on pinto bean pods. He volunteered for the job a few months ago when he was driving by and noticed that the garden might be in need of attention.

Painter has a long history of gardening, beginning as a child on the family acreage in Frisco, which was little more than a farming community back in the day. He remembers helping his father weed the large family garden, where they grew potatoes, okra, beans, cucumbers and plenty of vegetables.

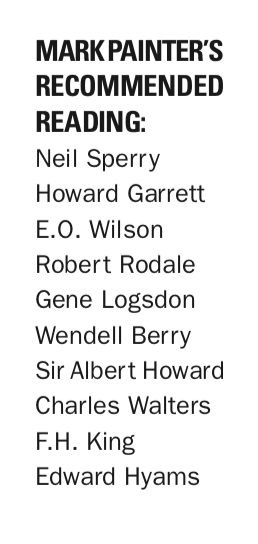

He was still in high school when he stumbled upon Organic Gardening magazine and the writings of Robert Rodale, Sir Albert Howard and others.

“They led me to compost, organic matter and nutrient cycles,” he says.

Armed with an elementary education degree from the University of Texas in 1971, Painter tried his hand at teaching, but he lasted only six weeks. Then he went to work in construction, doing remodels and repairs.

But the siren song of nature was never far away, and he and his wife, Evelyn, bought 50 acres in Arkansas.

“I was going to be a hippie and live off the land,” he says.

Eventually, they returned to Dallas, where Painter attempted the classroom a couple more times. It was never a good fit. While at Lakewood Elementary in the early 1990s, he planted a small garden to teach his students about empirical versus theoretical learning.

Painter and his wife both ended up at Mockingbird Elementary, where Evelyn asked her husband to plant a row of beans on the grounds for her students to observe. It took off from there. It would grow and flourish over the next few years, teaching students about gardening, states of matter, entropy, erosion and weather.

“It was the only thing that ever made sense to me,” Painter says. “It gave me meaning.”

He had hopes of working with students at Geneva Heights, but the pandemic put those plans on hold. For now, he happily maintains the garden there, and he also puts in time at Lake Highlands Community Garden, where he co-manages donations. This spring, the garden donated 70 pounds of potatoes, onions and squash to the local food bank.

At his home, Painter grows a few vegetables, maintains a vermicomposting operation and keeps eight chickens. As neighbors channel their inner gardeners or chicken farmers during the pandemic, he has a few words of advice.

Step one: Do your homework. Visit gardens and chicken operations you admire. Talk to the folks maintaining them. Ask them what’s involved. How much time and energy is required?

Painter admits that our blackland soil, a nutrient-rich strip running from Sherman to San Antonio, is great for growing crops. But here’s the rub: You must evaluate your site. Does your yard have sun, shade and roots?

Before you turn any soil, Painter encourages chats with those working at community gardens. Better yet, get your hands dirty. Volunteer your time. Then read up — even perspectives you might initially disagree with — before forming your own vision.

The same advice holds true for keeping chickens.

“It’s a lot of work,” he says. “Having chickens is good for kids to see where things come from.”

In the garden at Geneva Heights, crows caw in the background as Painter leans on the hoe. He mentions E.O. Wilson’s biophilia movement — love of and benefit from diversity of life forms — as a great influence.

“Our natural environment is deteriorating,” he says. “But we need all these organisms around us.”