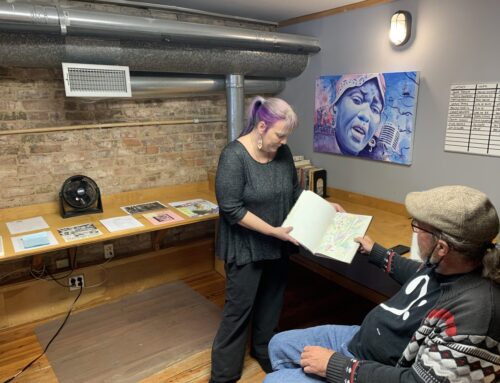

Principal Roxanne Cheek, in her fourth year at Lipscomb Elementary, says “the work is not done here by any means” but believes the school is “turning a corner.” (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

Last spring, in the midst of a heated school board election, three candidates in a close race to represent East Dallas, Preston Hollow and Oak Lawn schools were asked which school in these areas is the best-kept secret.

All three, without hesitation, gave the same answer: Lipscomb Elementary.

“The principal there is doing excellent work,” said the eventual winner and current Dallas ISD trustee, Dustin Marshall. “They have an magnificent two-way dual language program. It’s a jewel for the district that I think we need to replicate elsewhere.”

Lipscomb is the neighborhood school for three Old East Dallas historic districts — Junius Heights, Swiss Avenue and Munger Place — but in recent history, families living in the homes on these established streets haven’t sent their children to the school. An Old East Dallas early childhood PTA formed in 2008 to attempt to reverse that trend, with some success.

By the time Principal Roxanne Cheek took the helm of Lipscomb in summer 2013, the school had hit a rough patch.

Transparency and collaboration are the keys to Lipscomb’s success, Principal Roxanne Cheek says. “I don’t make any decisions without consulting my administrative team and looping my parents in.” (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

“The community distrusted the administration and vice versa,” Cheek says. “There was a lot of brokenness in our community and in the culture and the climate here.”

Her first order of business was to fill a whopping 20 vacancies in the teaching staff, left by people who “had a bad year,” Cheek says. “The teachers who returned were the people who were faithful to this community and loved Lipscomb.”

Cheek knew she had to rebuild, and she proceeded methodically and meticulously. Her first priority was to “make Lipscomb a welcoming place and a place where people want to be,” she says. Once that wheel was in motion, she turned to academics.

“International Baccalaureate [IB] came along at that point, and that helped give us a focus,” Cheek says of the holistic curriculum approach Lipscomb introduced nearly three years ago. She expects the school will be fully authorized sometime this fall, joining the ranks of J.L. Long Middle School and Woodrow Wilson High School, where her students eventually will attend.

Then there’s the dual language program Lipscomb launched last year, where native Spanish and English speakers are combined in a classroom to learn in both languages. Both dual language and IB are “a part of what makes Lipscomb special, but it is not what makes Lipscomb special,” she says.

The secret ingredient is what Cheek constantly refers to as “our team.”

“We have the right people in every place,” she says. “This year, there are fewer parent concerns because they love their teachers. I feel the same about our parents, who are constantly working for the betterment for our community.

“We’re all really rowing together.”

Keith Peeler, a Lipscomb dad who chairs the school’s site-based decision making (SBDM) committee, gives Cheek credit for her “dynamic job of hiring the right teachers.”

Peeler lived in the Park Cities when his oldest daughter, now at Woodrow, attended Highland Park ISD’s Bradfield Elementary.

“Outside of the fact that we just don’t have as many toys as they have, and the obvious money differences, I would put all of this year’s teachers toe to toe with any of the great instruction they had at Bradfield,” he says.

As Peeler points out, Lipscomb’s population is starkly different than Bradfield’s and even some nearby DISD schools. Nearly 90 percent of its students are economically disadvantaged.

Though Lipscomb has made some “fairly big improvements” in the last few years, says Alex Enriquez, another SBDM committee member, “We don’t have real estate agents putting the name of our school on the fliers yet. If you go to Lakewood or Hexter [elementaries], you see that.”

Enriquez lauds Hexter, where he attended elementary school, for its socioeconomic diversity that over time has been shown to benefit low-income students. Though Lipscomb is 90 percent low-income, the students zoned to the school are not. The neighborhood’s economic demographics are a fairly even split.

“If Lipscomb was just to attract families who already live in our neighborhood, we could recreate that,” he says of Hexter’s diversity, “and DISD needs dozens of schools like that.”

Enriquez lives in Junius Heights close enough to Lipscomb that he can see the school from his house. There are six children under the age of 5 on his small block alone. Young families are “waiting in the wings,” he says.

“The key is going to be to keep them there,” Enriquez says. “Our houses are relatively small by Dallas standards, and once their kids are 5 or 6 years old, it’s not any big deal to move to the M Streets or Lakewood or Coppell.”

Part of keeping them will require better marketing of the great school Lipscomb already is, he says, and part of it will require continued improvement. Enriquez, who heads the education-focused nonprofit City Year Dallas, believes it takes five years to turn a school around. Cheek is close to finishing her fourth.

Even so, she is the longest tenured principal amid Woodrow and its feeder schools, which had leadership turnover at every campus over the past two years.

“Time is of the essence,” Cheek says. “If you’re two grade levels behind, we still need time to close those [achievement] gaps,” and then there’s “the time needed to make a school well rounded and not just test focused.

Of 143 DISD elementary schools, Lipscomb ranked 139th on the district’s culture and climate surveys when Cheek arrived in 2013. That number rose to 97th the following year, then 55th last year and, now, 45th.

“It’s probably what school turnaround should actually look like when you’re allowed and given time to create your team and figure out what your priorities are,” she says. “We’re really trying to create a neighborhood school that people can be proud of, where people want to come to work, and we’re just on the precipice of that.”