In the early 1970s, a young urban planner by the name of Khan Husain took a keen interest in Lakewood. He had heard of the Abrams bypass, a city of Dallas proposal that would route traffic around the Lakewood Shopping Center and create a thoroughfare for East Dallasites to travel to the city’s central business district downtown.

With the city already investing in the area, Husain thought, why not identify additional solutions that could benefit the Lakewood business district and make the area more economically successful?

A planner ahead of his time, Husain partnered with merchants and Swiss Avenue Historic District residents to create a master plan for the Lakewood Shopping Center. At one of the first gatherings, he instructed them to walk around the center and record impressions, according to an October 1978 D Magazine story:

“The group found that if they crossed with the lights, it took five minutes to go from Skillern’s, on the Southwest corner of the Abrams-Gaston intersection, to the Mickey Finn’s Billiard Parlor, on the Northeast corner.” Shoppers “felt uncomfortable,” the group told Husain. “They took their lives in their hands when they crossed the street. … Virtually all of the problems they isolated could be traced to traffic and [decentralized] parking.”

The parallels between then and now are striking. What we have today is the same beast but a different animal.

In the ’70s, no one — neither the city nor the shopping center merchants nor even the surrounding neighbors, mostly of the “urban pioneer” ilk — were all that concerned with cyclists or pedestrians traveling to the center. It was a different time, and “the era of the car’s urban supremacy,” as writer Susan Dominus puts it in an April 2015 New York Times Magazine article.

“For much of the 20th century, when the engineers running urban transit authorities thought about traffic, they thought less about the pedestrian experience and more about saving money, by saving time, by speeding movement, by enabling cars,” Dominus states. “They analyzed traffic flow, the backup of cars, stoplight times and right- and left-hand turns, all in an effort to keep vehicles moving freely and quickly through the city.”

This surely was the impetus for the Abrams bypass, which proposed to expand Abrams from two to six lanes between Mockingbird and Columbia. The widening of Columbia was completed in the mid-’70s, connecting Main Street near downtown with Abrams just south of the shopping center. In a 1974 article, The Dallas Morning News lauded the new connection for offering “direct access to town for thousands of motorists in Lakewood and East and Northeast Dallas.” After the bypass’ completion, the story continued, “the Abrams-Columbia throughway will almost surely become one of the city’s busiest thoroughfares.”

The bypass was under construction as the neighborhood transitioned from a bedroom community to part of the inner city. Pretty much all of East Dallas between Lakewood and Central Expressway had been blanket-zoned as apartments in the ’60s, leaving the grand homes of Dallas’ early-1900s trolley suburbs in disrepair. Old East Dallas was then considered the worst of the city’s ghettos. By the ’70s, when the federal courts ordered Dallas’ schools to desegregate, white flight was in full force.

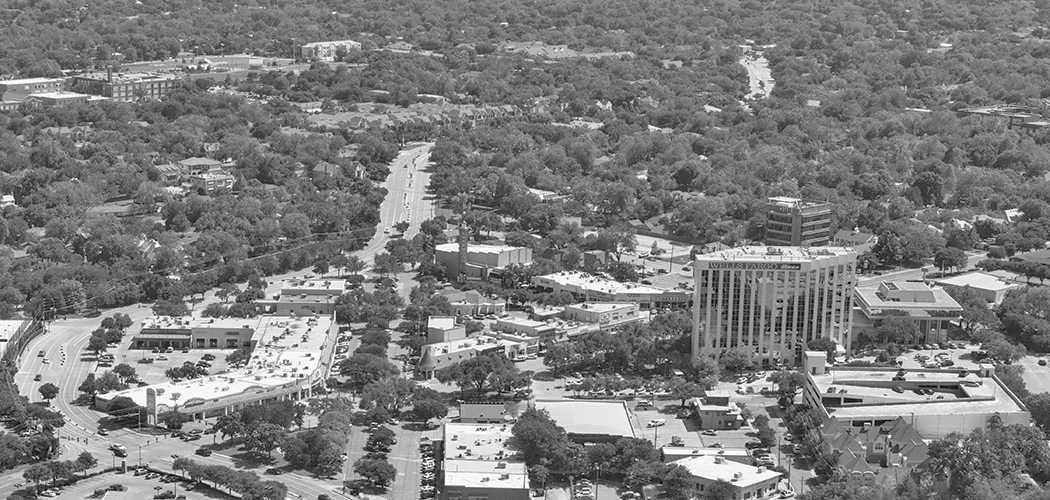

The Lakewood Shopping Center of the ’70s was a deteriorating relic surrounded by mostly dilapidated neighborhoods. Doc Harrell, who had outlasted every other shop around, died in 1969, and the Lakewood Theater was showing dollar movies in an attempt to survive. The shops in-between and north of Gaston weren’t primarily retail stores but service shops — dry cleaners, plumbers, repairmen, automotive — and merchants were concerned with clearing out traffic so their customers could park and pop in easily.

As the city’s thoroughfare committee worked to create more routes between downtown and Dallas’ more recently developed outer-lying areas where the middle class lived, it only made sense to build one of those roads through the old, abandoned East Dallas ghetto. Plus, for all intents and purposes, people traveling downtown already treated Abrams and Gaston as throughways. The meeting of “two racetracks” is how one woman described the intersection of Gaston and old Abrams at a 1981 city council meeting.

Considering the car’s urban supremacy, it’s a credit to Husain and the progressive-thinking group of merchants and residents that their master plan turned three blocks of old Abrams road into a pedestrian mall — or, at least, that’s what they intended.

The mall was to have “broad walkways and lots of benches and greenery,” according to a 1974 Dallas Morning News article. Parking would be eliminated from Abrams Mall and from most of Gaston, which would become a “classic tree-lined, 4-lane divided boulevard with a landscape median and broad sidewalks.” Abrams Mall would be interrupted by only one lane of one-way traffic, and other streets within the shopping center, including La Vista, also would be converted to one-way one-lane roads with partially landscaped malls.

The plan and its committee received the Mayor’s Award for its efforts toward “environmental quality.” Lakewood’s master planners were the first in Dallas to recognize this as “something more than measuring air and water pollution and solid wastes,” said environmental quality committee chairwoman Jo Fay Godbey as she bestowed the award.

“White flight would not happen if people had a sense of place where they belong and like to be,” she said in praise of the plan.

Plans — and perhaps urban master plans especially — don’t always come to fruition, however. The bypass did eventually receive council approval in 1981, after the city and county both invested $1 million and a decade of work in the project. But the “Abrams Mall” Husain and neighbors envisioned is now Abrams Parkway, which is, by default, a two-way street with four lanes of parking stretching from the initial curve of the bypass at Prospect to the final curve at Junius. There is no “pedestrian mall” to speak of, unless we’re counting the three-quarter-acre Harrell Park at Gaston and Abrams, where the Abrams bypass construction took out the old Skillern’s drugstore.

It’s unclear why. Likely it had something to do with a lack of funds, as both the city and business owners had agreed to foot the bill for the reimagined space. What is clear is that the city and neighborhood had hoped to make the Lakewood Shopping Center both a more pedestrian-oriented area and one that had the potential to attract more retail specialty shops and restaurants. This paid off for the business interests; it’s been years since anyone has described the shopping center as “run down.”

Neighbors, though, never really received the gathering place they were promised — and would have a hard time getting there on foot or two wheels even if it did exist.

See all stories for Dreams and reality: Lakewood Shopping Center