Dallas, like any densely populated and cosmopolitan city,

has a rich and disturbing history of crime

Dallas Police Museum: Photo by Danny Fulgencio

On the second floor of the Dallas Police Department’s Jack Evans headquarters is a room piled high with boxes containing a century’s worth of incident reports and arrest warrants, department newsletters and newspaper clippings. Vintage badges, patches and patrolman caps fill several glass display cases. Books containing city code and local true crime stories line metal shelves, and a heavy, rusty ball-and-chain leg cuff occupies a dark corner.

Dallas Police Senior Cpl. Rick Janich, curator of the forthcoming Dallas Police Museum, is working to transform these artifacts into a proper exhibit. Meanwhile, when his schedule permits, he shows visitors around, allowing them to sift through handwritten records and black-and-white photos. He might even show off the collection of handguns and badges, stashed under lock and key, that once belonged to famous lawmen such as Prohibition-era police chief Elmo Strait.

The museum will be a popular attraction — after all, the Dallas Police Department has groupies, Janich explains.

Fans of the show ‘Dallas SWAT’ will show up at police headquarters looking for stars of the reality TV show, he says, “hoping for an autograph.”

Perusing the evidence, there is no reasonable doubt that our neighborhood has been the scene of some of the worst criminal offenders and best detectives in history.

THESE ARE THEIR STORIES.

Robert Sadler and his pursuit of the “Friendly Burglar Rapist”

Private detective, author and artist Robert Sadler in central Dallas, where he began his career: Photo by Danny Fulgencio

Retired cop Robert Sadler — a White Rock-area resident who now works as a writer, artist and private investigator — kept some of his old notepads. On one page is scrawled a profanity-punctuated rant. Sadler says he wrote it in the late 1970s, probably while sitting in his car in the middle of the night, overlooking a cluster of Vickery Meadow apartments where he was hunting a serial rapist.

“Trying to be vigilant and for what? … To catch the man the department doesn’t give a damn about? And for what, I keep asking myself. The victims care. Tom and I care. I guess we care, but no one else.”

As the head of the Central Police Division’s Crime Analysis program, catching this serial rapist was not Sadler’s job, but it had become his obsession.

Sadler and partner Tom Covington were equally preoccupied with tracking the movements of the rapist. They pursued a single-perp theory even when the brass told them they were wrong.

Armed with data from exhaustive research, they shared their theories with senior investigator Reba Crowder, Sadler says, but she dismissed them. She believed that the rapes were the work of several different perpetrators.

Not content to sit by, Covington and Sadler say they spent hours in the field surveying the rapist’s ground.

“We wanted to refine our feel for where and how he was moving through his turf, and we were constantly looking for him,” Sadler says.

Concedes Sadler, “This is my side of the story. Some in the department might say, ‘Sadler is full of it.’ ”

But events following Crowder’s departure from the case show that Sadler and Covington were on the right track all along.

Today, thanks to DNA forensics, sex crimes are easier to connect and solve than they were 40 years ago.

The 1970s serial rapist whom Sadler and Covington were tracking terrorized approximately 80 East Dallas women over a period of three years before police finally nabbed him.

“I wish we had DNA evidence back then,” Sadler says. But DNA would not be broadly available in crime solving for another 15 years.

Sadler led the behind-the-scenes effort to catch Guy William Marble Jr., who was dubbed, during the height of his infamy in 1977, the Friendly Burglar Rapist, or FBR.

Had it not been for the innovation, creativity and persistence of Sadler and Covington, the clever and clean-cut Marble — a husband, father and advertising exec by day — might have eluded the law and continued raping much longer. Sadler and his partner believed the FBR’s crimes followed a pattern that eventually would lead to murder if no one stopped him.

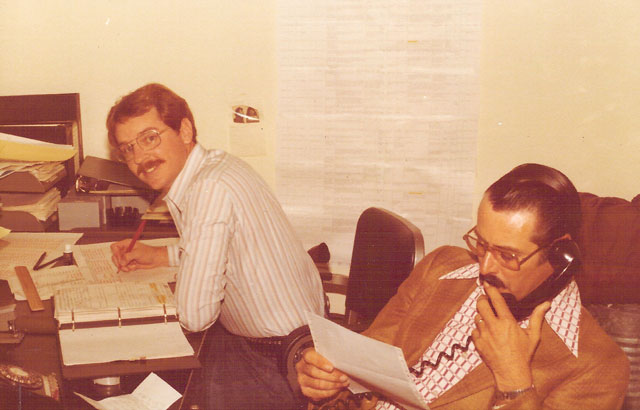

Crime analyst Robert Sadler and partner Tom Covington collect data, using innovative methods to track down the so-called “Friendly Burglar Rapist.”

In the late 1960s, Sadler was tough and streetwise — a Vietnam vet and a beat cop who joined the force when he was just 20. He worked undercover, at times posing as a wino. And he was exceptionally creative.

“I went to Oklahoma State University to major in fine arts with the intent of being a painter,” he says. “But [the core classes] bored me. A comedy movie inspired the idea of joining law enforcement.” Because he was a minor, he had to be legally emancipated before he was sworn into the department in 1968.

In 1972, when the DPD started a crime analysis program at the Central Patrol Division, they tapped Sadler to oversee it. Sadler’s artistic inclinations made him a good choice.

He placed large city maps on his office wall and used stickers to plot crimes — a retro version of today’s info-graphic.

“The visuals helped. I think it forced the sergeants and [subsequently] beat cops to take more accountability for their neighborhoods,” he says.

When a man began terrorizing area women — chatting in their ears as he raped them, telling one he was her “Friendly Burglar Rapist” — Sadler was the first to notice a pattern.

In 1974, he noticed a rape report strikingly similar to one he had reviewed several months prior. At the time, Sadler was analyzing only Central Division reports.

He asked his chief, Robert O. Dixon, for access to citywide reports. Sifting through thousands of them, he determined about 10 cases altogether could possibly be linked. And then the reports kept coming.

Sadler noticed multiple connections: Most of the rapes occurred in the Northeast Police Division’s Vickery Meadow area, then a bustling community for young singles. The attacker stalked his victims, looking for plants or other indicators of a female occupant. Donning a nylon mask, he typically entered unlocked doors or windows while the women slept. He cut phone lines, which he later used to bind his victims. He stole money from the complainants’ wallets and usually removed their IDs (later, Marble would admit to investigators that he enjoyed seeing the photograph, age and description of the woman he would be raping). A woman in her 60s was among his victims. A mother and her adult daughter were victimized in two separate incidents. He covered women’s heads with pillowcases or pulled their own nightgowns over their faces. He held his knife to many throats but never cut anyone. Victims described him as “polite.”

One victim got a good look at her attacker. Unlike today, the department did not employ a sketch artist, but the witness worked with an unofficial artist to develop a composite drawing.

Incoming investigators John Landers and Truly Holmes listened to Sadler and Covington, and they directed a tactical team to stake out a specific area, a Vickery Meadow complex, based on the researchers’ data and predictions.

Just a few nights later, on Valentine’s Day 1977, Officer Barry Whitfield spotted Marble peeking into apartment windows there and apprehended him.

Whitfield was lauded as a hero, but he credits Sadler and Covington.

“The Dallas Police Department took a quantum leap forward in the area of crime analysis as a result of their work,” Whitfield recently noted.

The media light never shined on the two behind-the-scenes researchers, but through a 1977 commendation, investigators acknowledged that the men led police to the rapist.

“These officers were more knowledgeable than anyone in the department when it came to the ‘Friendly Burglar Rapes,’ ” wrote investigator Truly Holmes. “The information they amassed resulted in their accurately predicting the next movement of the rapist.”

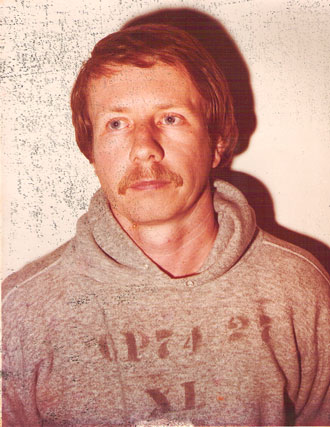

“Friendly Burglar Rapist” Guy William Marble, Jr.

In custody, Marble confessed to 81 rapes. Charged with various counts of rape and aggravated burglary (which at the time carried a heavier sentence than rape, according to presiding judge Henry Wade), he was sentenced to 60 years in prison, but he was eligible for release after 20 years. In May 1998, the 51-year-old Marble went free.

While in prison Marble married a French woman. Paperwork shows he was denied a French visa. Sadler says no one is sure where he is now.

“We do know that he was supposed to register as a sex offender and never did,” he says.

Several things changed in the Dallas Police Department during Sadler’s years as a crime analyst.

For example, Sadler developed a standardized list of questions requiring officers taking a crime report to ask for specific descriptions — height, weight, hair color, eye color and ethnicity of suspects, for example. This gave analysts a more focused list from which to draw connections between crimes.

In addition, improvements were made in the way law enforcement treats victims of sexual crimes.

“Victim blaming was rampant in those days — in the department, in the media — stories about the victims’ lifestyles and how they invited the attacks ran in the paper,” Sadler says. “Great strides were made in rape-crisis counseling and education during the FBR era, aided in no small measure by Tom Covington’s wife, Janie Covington.”

Janie Covington volunteered at Dallas’ Rape Crisis Center, spent long nights at Parkland Hospital with victims and lectured publicly about prevention and how to cope after an attack.

“The rapist’s three-year spree opened a multitude of doors in crime prevention,” Tom Covington notes. “All of the publicity that came from [this case] helped change the public attitude about rape.”

It is clear that Guy William Marble Jr. — the years searching for him and the fact that the old man is free and unregistered — still occupies a large space in Sadler’s head.

In 2012 Sadler published a 540-page book documenting his experience. The tome, “One Step From Murder: The True Story of the Friendly Burglar Rapist,” is dedicated to Covington, Chief Dixon and the victims: “To the women of Dallas who were the prey of the FBR,” reads the opening page, “Tom and I never forget you.” —Christina Hughes Babb

Neighborhood resident Robert Sadler’s book, “One Step From Murder,” about his hunt for a serial rapist in the 1970s, is available on amazon.com.

Two-Timed: How the Dallas Police Department is using social media to keep cold cases — and other important information — hot on our minds

On Sept. 21, 1988, Dallas police officers responded to a call at 6257 Lakeshore Drive. The victim, 41-year-old Jill Bounds, was supposed to meet a friend. When she did not answer her door, officers entered the house. Bounds was found deceased in a bedroom with blunt force trauma. Leads developed at the time did not result in an arrest. Twenty-six years later the case remains open, documented as case No. 609517-W.

This is the kind of information neighbors can find on the Dallas Police Department’s new blog, dpdbeat.com, which launched in February to help police disseminate important information.

“We did that for several reasons,” explains Maj. Max Geron. “No. 1 was because it’s another avenue to be able to release information to the public and the media at the same time.”

Historically, police have relied on partnerships with local media in order to propagate information to the public, but there is a finite amount of space and time that news outlets can dedicate to the police beat.

Although media partnerships are still important to the police, social media has given the police department a platform that allows it to skip the middlemen and release as much or as little information as needed, directly to the people who need to see it.

There’s a wealth of information available on dpdbeat.com, including a list of cold cases, such as the aforementioned case of the East Dallas woman found dead in her home.

“Before, there was really no other place where you could have gotten this stuff,” Geron says.

“There were some news agencies that would do an occasional weekly feature on a cold case, and they’d go out and interview a detective or whatnot, but there was no way — that we could see — for us to put this information out there,” he says. “And the blog gave us a place for that.”

Aside from the blog, the Dallas Police Department is ramping up its use of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

In August, the Dallas Police Department launched a YouTube series called “In Depth.” In each episode, Sr. Cpl. Melinda Gutierrez interviews a detective about a case, going over “pertinent facts and information to get a fresh set of eyes in the community on the cases,” Geron says. “To see if there might be additional information to help us solve the case.”

In August, the Dallas Police Department launched a YouTube series called “In Depth.” In each episode, Sr. Cpl. Melinda Gutierrez interviews a detective about a case, going over “pertinent facts and information to get a fresh set of eyes in the community on the cases,” Geron says. “To see if there might be additional information to help us solve the case.”

Because of the video series, the police have already had at least one instance where additional information helped move a case along, Geron says.

So far they have filmed two episodes of “In Depth,” and the media relations office has been studying up on what it can do to make the videos as professional as possible.

“We’re a content provider,” Geron says. “We have access to certain information — some of which we can release, some of which we can’t. But this way, you get to talk to the detective, who has firsthand information about the case. He or she knows what is acceptable for release and what might jeopardize the case were it to get out. We want them to feel comfortable with what’s going out to the public.”

In addition to “In Depth,” the Dallas Police Department YouTube page features a series called “A Day in the Life,” which gives a behind-the-scenes look at various departments in the police department. There are also several press conference recordings available.

The website and social media pages also allow the Dallas Police to disseminate information during emergency situations, Geron points out. The department is working on gaining more followers to increase its reach to the community.

Since the department launched dpdbeat.com, it has received almost 1 million views.

The department has more than 54,000 followers on Facebook and 42,000 followers on Twitter.

The Twitter account in particular has been a game changer for the police department during breaking news situations.

“By utilizing Twitter from the scene of an ongoing incident, we are able to deliver factual information — or at least as close to factual information as possible — immediately,” Geron says.

“When we talk to people, they say, ‘Hey, you guys are leading the way on social media,” he concludes. “It’s just been revolutionary. And it’s fair, and it’s balanced distribution of information, and in my line of work that’s imperative.”

Links to know:

dpdbeat.com

facebook.com/dallaspd

twitter.com/dallaspd

youtube.com/user/dallaspolicedept

Remembering the shotgun squads

In the mid-1960s, armed robberies became a problem at convenience stores, restaurants and liquor stores, according to Sr. Cpl. Roderick Janich, who curates the Dallas Police Department museum.

Robbers would walk into a store, shoot the clerk at point-blank range and then empty the register. The death toll was rising, and the Police Department intended to stop it.

Lts. Herman Holloway, Jay Finley and Harry Dean Thomas came up with a solution: shotgun squads.

Patrol officers would work overtime — a competitive status among officers — to aid shotgun detail, Janich says.

The shotgun squads involved dangerous stakeouts during which officers would camp out for hours at a convenience store or restaurant, often in less than desirable conditions, and wait for a shooter.

Although it seems like an undesirable job, Janich says the officers usually jumped at the opportunity for overtime and extra money.

Sometimes the officers would sit in dark alcoves, storage rooms or freezers, and they joked that the process was “seven hours of boredom and three seconds of sheer terror when confronting a hijacker,” according to a retired sergeant, T. Wafer, who picked up shifts with the shotgun squad whenever he could.

Different time, different place.”

Wafer was eventually promoted to supervisor, surveying possible shooting locations.

“I had walls and two-way mirrors installed at the sites’ expense,” Wafer says. “They wanted the protection for their employees. We had chairs installed and other things to make an officer comfortable in these long, boring stakeouts.”

When the time came, the officers didn’t hesitate to shoot the robber where he stood.

Today, officer-involved shootings are met with scrutiny by the media, the public and the Police Department, but things were different in the 1960s.

“Back then, they shot felons,” Janich says. “You came in, boom, they shot you. They didn’t mess around. Different time, different place.”

Once word spread, the fear that there may or may not be officers camping out at any given convenience store was enough to cause the number of armed robberies to plummet.

Although shotgun squads no longer exist, a police presence at convenience stores still deters unwanted activity.

“The concept is still used today for crime prevention,” Janich says. “Convenience store clerks will hang old police jackets in their stores, just to give the idea: ‘Is there a police officer here?’ We went through a phase one time where we’d put cardboard cutouts of police officers in convenience store windows. And, of course, decoy cars in shopping centers.”

Hall Street Shoot-out

There was nothing remarkable about Johnny Lee Thomas — nothing that would put him on the Dallas Police’s radar, at least.

Until 1969, the 26-year-old lived in relative anonymity with his aunt and half-brother in a small house on North Hall Street between Central and Ross.

On Sept. 27 of that year, he brought home a long-barreled shotgun and sack of shells. Two nights later, he got up from the dinner table, retrieved his gun and told his aunt, “I’m going hunting — all by myself.”

Then he walked out the front door, turned to the house next door to him and shot in the face 16-year-old Aljewel Wesley, who was on the porch playing records with her boyfriend and grandmother.

And thus began the rampage that has been termed “The Hall Street Shoot-out,” which E.R. Walt, a retired Dallas police captain, writes about extensively in his book of the same name.

Thomas shot another unsuspecting neighbor, Frank Henry Buford, who died almost immediately, and he tried to shoot his own half-brother at point-blank range, but the chamber was empty. He then shot the first three police officers to arrive on the scene.

One of the wounded officers managed to call for backup, which resulted in dozens of police officers throughout Dallas dropping everything to respond. As Walt explains, “a brother was in trouble,” and should the day come when they needed the same assistance, “they wanted their comrades to respond in just such a fashion.”

The first officer to arrive on the scene shot Thomas squarely in the chest with a Colt .45, but the wound didn’t fell him. Rather, Thomas barricaded himself in the house at 1904 Hall Street and was soon surrounded by more than 100 officers from all over Dallas and beyond.

“Johnny Thomas was no longer hunting,” Walt writes. “He was now the fox that had been run to ground … and the hounds were gathering.”

Walt participated in the resulting gunbattle, which involved more than 1,000 rounds of ammunition and a bout of tear gas, but his book is far more than a personal perspective of the event, which he considers to be “the biggest gunbattle” in the history of the Dallas Police Department.

“The Hall Street Shoot-out” takes readers through every step of the exchange and even dissects the impact of tactical decisions — or lack thereof, in some cases — by explaining the historical context behind some of the regulations, which often placed significant limitations on the acting leadership.

As a result, the battle on Hall Street was nothing short of chaotic.

As more and more officers arrived, they took cover behind anything they could find, which for some was nothing more than tall grass or bushes.

Every so often, Thomas would fire out of a window or door, and a volley of pistol and shotgun fire would answer. Then he’d go to the other side of the house and do it all over again.

At times, Thomas would run frantically from one side of the house to the next. Other times there would be long stretches of silence, until officers began to wonder if he’d been hit.

“To the cops assembled there, it was a new and unique experience,” Walt explains. “Not being shot at, as that had happened to most of them … It was the sometimes leisurely pace of the fight and the camaraderie involved that was different.

“Between bursts of action, there was time to discuss events with the officers at one’s side and to think and plan for the next bout of action.”

Police attempted to force Thomas out of the house with tear gas. In those days, only a chief could give permission to use the tactic. As a result, “a sergeant was on scene with the gas for many long minutes before a chief officer could be located to give permission to deploy,” Walt writes.

In the end, the gas didn’t appear to faze Thomas in the least.

One of the greatest errors of the incident, Walt writes, was the “failure to have personnel trained and armed to respond to active shooters and barricaded persons.”

Only half of the 100 or so officers who responded to the shoot-out came from the Police Department’s tactical units, the beginnings of what we recognize as SWAT teams today. The other half were “young, energetic officers ready to jump into any action,” Walt writes.

At the time, the term “active shooter” hadn’t been coined yet, Walt says — and he concludes it would be “unfair in the extreme to expect such extraordinary foresight from the administration of the Dallas Police Department when no other major police department had yet realized the need to defend against the emerging threat of mass shootings and barricaded persons.”

However, the officers did eventually succeed in bringing Thomas down in perhaps the most dramatic scene in the book.

During one round, a blast of buckshot hit Thomas in the side of his head and forearm. Then another hit him in the middle of the back, Walt writes.

Thomas walked back to the bedroom, where he put a Jimi Hendrix album on the record player and turned it up as loud as it would go, until the officers could hear “Purple Haze” blaring from outside.

A hot grenade had caught the front of the house on fire, Walt says. As officers watched, tongues of flame began to brighten the house as they crawled up the wallpaper. A cotton mattress, which Thomas had been using as cover, also caught fire.

Inside, Thomas stumbled through the house, paused at the front door to reload his shotgun and then stepped onto the porch, “his dark figure silhouetted by the growing fire behind him.”

All the officers could hear was the “quiet crackle of the flames and, seeming to come from far away, the driving beat of Jimi Hendrix,” Walt writes.

Someone yelled for Thomas to drop the gun, which snapped him into focus. With what seemed like a smile, he slowly raised his gun; he was answered by a roar of gunshots that “held Johnny Thomas erect in the flurry of bullets for a long moment, the unfired shotgun at his shoulder.”

Finally, he toppled to the floor. Someone yelled that he was still moving, but he wasn’t.

Thomas was dead.

Not including Thomas, the rampage left one dead and six wounded, including four police officers.

For more information, order a copy of “The Hall Street Shoot-out” on amazon.com

[divider scroll_text=”Go To Top”] [space height=”20″]