On a sunny Thursday afternoon, Jackey Attaway and Wayne Donehoo drive onto a piece of property that most of us would rather not visit.

A group of suspicious-looking men standing in a circle scrutinize the pair of Dallas City Code inspectors invading their space.

Donehoo and Attaway are there to inspect a San Jacinto Street apartment complex ordered by Dallas Code Enforcement to undergo repairs or face demolition because of various violations.

Donehoo, a short, stout man often described as a “bulldog”, spots two old cars he says have been in the rear parking lot of the complex for months – a violation of the junked vehicle ordinance.

One of the men in the group approaches Donehoo and explains he is repairing one of the cars. The man becomes irate when the inspector asks him to start its engine.

When the man makes no effort to start the car, Donehoo warns him he must prove that the car is running.

Attaway, who is watching from their car, becomes concerned for his partner’s safety.

“I wish he would get in the car, I hate it when he does that,” Attaway says.

Later, as the two drive off the property, he reprimands Donehoo.

“That guy could have pulled a gun on you – you shouldn’t have done that,” Attaway says.

Donehoo is silent, but nods in approval.

“I know,” he says. “We can always come back another day.”

As it turns out, the man didn’t pull a gun on the inspector and, during another inspection a few weeks later, the car started. But both men know the situation could have ended differently.

“A few years ago an inspector was shot during an inspection,” Donehoo says.

“But somebody’s got to do this. The police take care of things on the street and we take care of things in the yard.”

Why We Need Code Enforcement

Jackey Attaway and Wayne Donehoo are the quintessential inspectors, the Starsky and Hutch of Code Enforcement, sometimes treading on dangerous territory to make sure neighborhood property owners are obeying our City’s building codes so that we may live in a healthy and safe environment.

“They make things happen, and they don’t put up with much crap – they’re bulldogs,” says Kevin King, a Dallas police officer who coordinates residential crime watch programs for our area.

They help keep neighborhood streets clean, property values higher and living conditions acceptable. They are, according to one City Council member, “critical to maintaining a healthy community.”

King says he continues to see improvements in East Dallas apartment complexes because of Donehoo and Attaway’s tough code enforcement.

“It’s a proven fact that apartments in disrepair are the ones that attract the criminal element,” King says. “Donehoo and Attaway are good at what they do, and because of that, they’re in great demand.”

What They Enforce

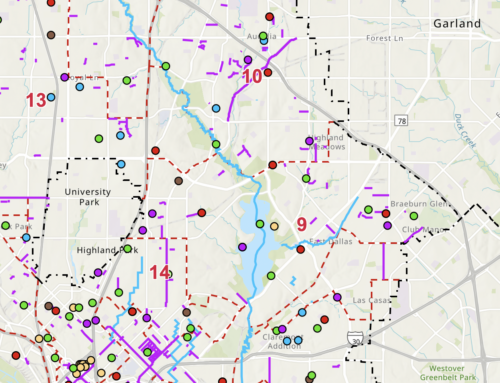

Donehoo and Attaway are part of a 20-inspector crew from the multi-family division assigned to enforce ordinances pertaining to the City’s apartment complexes and condominiums.

Inspectors have the power to enforce hundreds of litter, junk-vehicle, nuisance, building, graffiti and zoning codes, according to Ramiro Lopez, assistant director of Dallas’ Code Enforcement Department.

A separate division of inspectors (about 90) enforce the ordinances homeowners must follow.

They cruise our streets looking for residents who put bulk trash outside their homes earlier than the designated time, abandon junk cars, allow grass and weeds to grow more than 12 inches tall, illegally dump trash, stack wood and other objects higher than 18 inches from the ground, set up a business in a residential area, or post illegal garage or “for sale” signs in telephone poles.

“If there’s no one to tell these people what to do, then they won’t do it,” Attaway says.

The inspectors respond to as many as 15 complaints a day from residents who have called the City’s 24-hour Action Line (744-3600). On top of that, they are responsible for annual inspections of 200 apartments for minimum housing standards, something now required before a multi-family license is issued.

The two men say they also spend a considerable amount of time completing paperwork and in court, where they testify about properties they have inspected. Both say they wish they could spend more time on the streets, “doing their job and looking out for people.”

“We’re doing as much for the landlord as we are for the tenant, because in some cases we could prevent an apartment owner from being sued,” Attaway says.

“We’re working both sides at the same time.”

The Neighborhood Angle

Don Davidson, president of the Hollywood Heights Santa Monica Neighborhood Association, says members depend on code inspectors to enforce ordinances governing architectural styles in their neighborhood.

“Code Enforcement is very important to us, because Hollywood Heights is one of, if not the largest neighborhoods of Tudor-style homes in Dallas,” Davidson says.

Because of this, the neighborhood has been declared a conversation district, and homeowners must secure permits before certain structural work is done on a house. Davidson says members felt the ordinances weren’t being adequately enforced, so last year they began meeting with inspectors to discuss their concerns.

“In the last several months, there have been dramatic improvements,” Davidson says.

“We need Code Enforcement because we don’t have anything to make them enforce these ordinances with.”

The Process

After a caller, who may remain anonymous, has made a complaint, inspectors have 10 days to respond before a resident may take recourse – a call to the district manager.

Larry Holland, an analyst with Code Enforcement, says there are approximately 150 different types of complaints, and in most cases they involve premise complaints, which include weed, litter, junk car and illegal storage violations.

Following a complaint, inspectors visit the property and issue a notice of violation, which includes an order to correct the problem.

If the owner doesn’t comply, a citation is sent to the owner or, if the problem is serious enough, the Urban Rehabilitation Standards Board. The board’s four panels, each of which meets monthly, consists of Dallas residents appointed by council members.

The board has the power to declare properties “urban nuisances” and order them repaired or demolished. Violating owners can be fined up to $1,000 a day.

Sometimes, the board will ask a non-profit agency to help disadvantaged homeowners make repairs to their property.

If a demolition order is issued, Code Enforcement staff members transfer the case to Public Works. The owner must pay for the demolition, or the City seizes the property.

The inspectors say they encourage owners to fix-up their property instead of demolishing it.

“The only ones who say they don’t like Code Enforcement are the ones who don’t want to spend the money to make the repairs,” Attaway says.

A Day On The Streets

Attaway and Donehoo are responsible for inspecting 400 City apartment complexes. The inspectors travel as a team because it is safer that way, they say.

Attaway recalls one day they encountered a man with “a needle in one arm and a machine gun in another,” during an inspection of a vacant East Dallas apartment building.

“It’s exciting sometimes – we’ve been in just about every situation,” Attaway says.

Occasionally, Attaway says they call police to accompany them on an inspection because of suspected drug or gang activity.

“The police didn’t even want to come over here,” Donehoo says, stopping in front of another San Jacinto Street complex. Recent improvements made to the property and the screening of tenants have made a significant difference, the inspectors say.

“This property has changed because the owner spent money making improvements. But then you have the ones (landlords) who won’t do anything,” Donehoo says.

Last year, inspectors located the owner of a complex on Bennett to inform him of various code violations. Most of the 50 or so apartments were open and vacant, high weeds and litter surrounded the building, and the two occupied units had no heat.

After months of failing to comply with the orders, the tenants were moved out and the building was boarded up. Today, the graffiti-adorned complex is vacant, but its breezeways serve as a meeting place for gang members and drug dealers.

The board has ordered the property’s demolition, but the owner’s lawyer is attempting to block the action. The inspectors say the criminal activity won’t go away until the building goes away. And more than likely, the City will end up footing the bill for the demolition, Attaway says.

Owners who don’t comply with codes are doing more than creating eyesores for the community – sometimes, they are putting residents’ lives in danger, the inspectors say.

Attaway recalls one landlord, who in an attempt to stop the flow of drug dealers, at his complex, removed a stairwell exit – a code violation. When a fire broke out near the exit, a mother and her small child had no way to escape and died inside the apartment.

Getting Tough

The inspectors say they have to be “tough when enforcing ordinances,” or landlords will drag their feet in making repairs. But both say they would rather see the landlord “get things cleaned up rather than tear a building down.”

“When landlords say we’re tough, what they’re really saying is that we’re enforcing ordinances,” Attaway says.

“A cop is not responsible for crime on his beat. But we’re responsible for everything these owners and tenants have done to their property,” Donehoo says.

“It’s hard sometimes, but we keep working at it,” Attaway says.

Council member Mary Poss, who represents portions of East Dallas, says she is a believer in the broken window theory: If you leave a window broken, it gives the idea that no one cares.

“Code Enforcement is a top priority of the Council,” Poss says.

Poss says she wants to send a message to “slumlords” that their lackadaisical attitude in keeping their property up to standard won’t be tolerated.

Last month, she testified before the board to ask for the demolition of the Rosewood Apartments, located on the corner of Ferguson and Highland. In addition to being a “neighborhood eyesore,” the deteriorating, unsecured structure welcomed criminal activity, Poss says.

In 1994, after standing vacant for more than two years, the new owners promised to make a series of repairs so the property would be safe and livable again. But after a year only minor cosmetic changes were made, a sign to Poss and others that the owner wasn’t serious about carrying out the repairs.

On February 6, the board voted to demolish the Rosewood within 30 days.

Poss says tough action by the board isn’t the only way to get offenders’ attention and prompt improvements to neighborhood properties.

Last year, the council voted to allow fines of up to $1,000 a day for owners who don’t comply with inspectors’ orders. The City also recently set aside one of the 10 municipal courts to deal solely with code violations.

The Special Ordinance Court will allow quicker processing of cases involving homeowners and landlords who violate City building codes.

Before the new court, property owners were lumped in with speeders and others accused of Class C misdemeanors.

Chronic offenders sometimes escaped harsher punishment by dealing with each citation separately, each time before different judges. With the Ordinance Court, the City can consolidate cases against a single owner and related to a particular property.

Poss also believes Assistant City Manager Ramon Miguez, who oversees the Code Enforcement office, is responsible for a more aggressive push by the department to enforce codes.

“I have a lot of confidence in him (Miguez) and his promptness in getting issues addressed,” Poss says.

Ups and Downs In Code Enforcement

Mary Jane Beamon, who heads the old East Dallas Coalition, comprised of representatives from 15 neighborhood associations, says she has seen a series of “ups and downs” in Code Enforcement.

“At one time, they were very lenient, and now they seem to have clamped down,” Beamon says.

Ramiro Lopez, assistant director of Dallas’ Code Enforcement Department, says inspectors are “doing their job” in answering complaints despite criticism their response time is slow.

And that’s a difficult task considering there are just over 100 inspectors for a City with a population exceeding one million, Lopez says.

“If you stop and think about the simple mathematics of this, it’s just not enough,” Lopez says.

A study conducted by Lopez three years ago showed that cities the size of Dallas (Los Angeles, San Antonio, Phoenix) had twice, sometimes even three times as many inspectors. Lopez says.

The number of inspectors has remained the same for the past two years despite requests for an increase in manpower, Lopez says.

“Like other departments, we’re trying to do more with less.”

Lopez says during the past 10 years, City residents have begun utilizing the Code Enforcement department more frequently.

Unfortunately, he says, the department now has a problem trying to keep up with demand.

“We’re now expected to provide the same level of service that the police do, but with 100 people,” Lopez says.

“What is happening is we’re going through some growing pains. But we still continue to achieve results, and we’re always looking to improve what’s there,” Lopez says.

Beamon agrees that code enforcement improvements are occurring.

“The City has been great in listening to us,” Beamon says.

Inspectors are “doing the best they can do,” she says. “Some of them could use some training in psychology to better handle people.”

“I think we’re making some progress – I keep telling people to be patient,” Beamon says.