Neighbors who in their golden years are making the world a better place

Story by Rachel Stone and Christina Hughes Babb

Photos and video by Benjamin Hager

Mark Twain once said, “Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things that you didn’t do than by the ones you did.” A few neighborhood residents embody that truth, even as they reach their golden years. Their life experiences have inspired them to make every moment count toward noble causes and interesting pursuits.

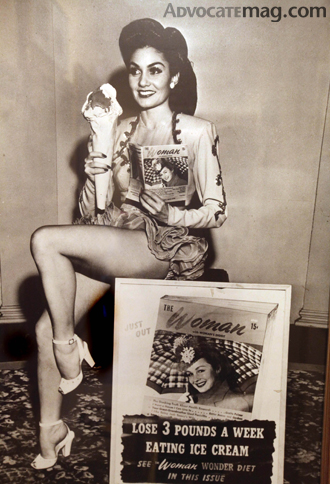

She was a showgirl: Willetta Stellmacher

Willetta Stellmacher attended one day of high school at Woodrow Wilson in 1931, and she never went back.

“They kept me in the office all day,” she says. “I thought, ‘Well, I can learn more in vaudeville than I can in high school.’ ”

By then, Stellmacher had been working as a dancer in nightclubs for more than a year. She wore makeup and short skirts, and she didn’t look like a 14-year-old high school freshman.

Later, she was denied a job at a Lakewood five-and-dime because she didn’t have a high school diploma. So she joined a vaudeville troupe, sparking an entertainment career that would span decades and take her throughout the country and into the homes of America’s rich and famous.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9PZMk9tCi5Q[/youtube]At 94, Stellmacher is known for her historic home on Gaston at Swiss and her annual White Rock Marathon party. In the ’40s, she says she stood up to the male business establishment in Dallas when it tried to intimidate her after she opened a children’s clothing store in Lakewood.

“They heard I was a chorus girl and didn’t know anything about business,” she says.

And in the ’80s, she was an Old East Dallas landlord whom a newspaper reporter dubbed “pistol packin’ mama” for fiercely protecting her rental properties.

She lived in Hawaii for 12 years. She’s had a few husbands, two children, a granddaughter and lots of friends.

It’s been a heck of a life.

Stellmacher keeps her show biz memorabilia in a hallway near her kitchen. There’s Danny Thomas. There’s the guy who whistled the “Andy Griffith” theme song, and there’s Lawrence Welk and Perry Como. But most striking are the pictures of Stellmacher herself, an intensely beautiful brunette with knockout gams.

She was born in Lewisville, and she and her mother moved to an apartment on Fitzhugh at Gaston when she was 2, after her parents divorced. When she was a student at David Crockett School, a friend was taking dance lessons at Ruth Laird’s Texas Rockets studio. Stellmacher couldn’t afford them.

“So she said, ‘I will teach you everything I know,’ ” Stellmacher says. “She taught me every step and every routine.”

She and the friend, Mita Norman, started working at the El Tivoli nightclub in Oak Cliff, the Baker Hotel Downtown and the Baghdad club in Arlington.

Ruth Laird eventually took the talented young dancer under her wing, offering Stellmacher lessons if she would teach the little kids at the studio.

Through her vaudeville connections, Stellmacher later got a job with Dorothy Durbin at the Edgewater Hotel in Chicago. She worked as a chorus girl there for eight years.

She also danced on Jackie Gleason’s stage show in New York, and she was accepted as an early member of the Rockettes at Radio City Music Hall, even though she was 2 inches too short. She quit after two performances because “they treated you like dirt, and I had wonderful respect at the Edgewater.”

For 16 years, she dated Joe Piscetti, who was a close friend of Frank Sinatra, a nephew of Al Capone and a guy who was, ahem, well-connected in Chicago.

She remembers sitting in Piscetti’s room at the Waldorf in New York one day. He was having a card party, and she was crocheting a bedspread, “if you can believe that,” she says. And someone mentioned that Walter Winchell had written in his column that Stellmacher was in town, and that she was going to take a Hollywood screen test.

She didn’t want to take the test because she thought movies were “silly.” But Piscetti wanted her to take the test, so she did. It was one of the first screen tests in Technicolor. She tested so well that MGM offered her a seven-year contract, but by then, Piscetti had a change of heart and told her not to sign it, so she didn’t.

“He said, ‘Well, now you can say you turned it down.’ ”

After her dancing career, Stellmacher was a model, which she says paid better than dancing. She was the Cook’s champagne girl of 1940. And her full-page picture appeared in the first four-color process edition of the Chicago Tribune in 1944.

Stellmacher bought her house on Gaston in 1987 and restored it over the following years. She has donated money and volunteer hours to Disciples of Trinity and other philanthropic causes over the decades. She recently overcame a broken foot and pneumonia. And she reminds us to do things while we’re young since they’re not as easy to do at 94.

But she still likes Cook’s champagne, a bottle of which we popped for an 11 a.m. photo shoot.

“Elizabeth Taylor always drank champagne for breakfast,” she says. “So did Onassis.”

Say hello to Mama: Freda Davis

Regulars to the Disciples of Trinity thrift store on Gaston know “Mama.” Most of them want to give her a hug when they stop into the store to shop.

Store owner Jim Davis calls her “Mother,” because she’s his mom. Freda Davis, 91, works at the DOT thrift store every day. Some people think her name is Dot and that she’s the owner. But the organization is actually a nonprofit Jim Davis started about 20 years ago to help terminally ill people.

His mom has been deaf since birth, and she’s had an often difficult and almost always interesting life. He couldn’t keep her away from the store if he wanted.

“She loves seeing people,” he says.

Freda Davis has an eye for fashion and often helps customers choose outfits and accessories. Jewelry sales at the store have increased since she started wearing pieces in the store, Jim Davis says.

Because of the language barrier, she takes customers’ physical cues to pick up on what they are looking for without them asking, he says.

Freda Davis was born in a rural community near Sulphur Springs, and doctors told her parents she was mentally retarded. Because of that, she was mistreated by her five older sisters and made to work all day in the fields while they went to school.

She finally was diagnosed as deaf at age 7 and sent to the deaf school in Austin. It was lonely at first because she didn’t know how to sign, she says, but once she learned sign language, her life started to blossom. She moved to Dallas at 19 or 20, she says, and met her husband, who was hard of hearing, at First Baptist Church. They had three children, and Davis immersed herself in her husband’s family, which was loving and supportive.

She and her husband, George G. Davis, operated an interior decorating business, and she worked with the city’s top designers. After her husband’s death in 1956, she took over the business and ran it for many years. She says she liked making draperies and pillows, and she had the opportunity to meet a lot of people.

Sometimes Jim Davis tries to convince his mother to stay home from the store if she isn’t feeling well. But around midday, she’ll show up anyway.

She likes to dust and do paperwork. When children come into the store, she often befriends them and keeps them busy while their parents shop. She likes to joke and make people laugh.

“She can’t stand having nothing to do,” Jim Davis says. “A lot of people feel like this is mother’s store.

Yay! Mr. Oddo’s here: Anthony Oddo

On a sunny Thursday afternoon, a bunch of Hillcrest High School students made an unusual exclamation, considering they are teenagers: “Yay! Mr. Oddo’s here.”

Anthony Oddo of Lakewood is an 87-year-old substitute teacher at Hillcrest and North Dallas high schools, where students love him.

“His rapport with my students is excellent,” says Hillcrest French teacher Drew Davenport. “His stories are dynamic.”

When Oddo teaches history, he sometimes has the unusual opportunity to speak from first-hand experience. He was an infantryman in World War II, serving in England, France, Luxembourg and Belgium. He lived through the Great Depression, which forced his widowed mother to bring Oddo and his siblings from Tampa to live with relatives in Dallas when he was a kid. He attended North Dallas High School.

“Mama, bless her heart,” Oddo says. “All she could do was barely pay the rent. I never even thought I would go to college.”

But he attended SMU on the G.I. Bill, and he graduated with a business degree. Afterward, he opened a small grocery in South Dallas. It flourished for about 10 years until construction of the R.L. Thornton Freeway led to its ultimate failure. That’s when Oddo joined the postal service, where he served as a mail carrier in the upper Greenville Avenue area for 21 years.

He bought a house on Richmond when he was 29, and he has seen the neighborhood change from mostly homeowners to mostly renters, although, “It’s held up pretty well,” he says.

After retirement from the USPS, he had no intention of stopping work. He started as a DISD substitute 10 years ago. Although Oddo was married four times, he has no children.

“I love to teach,” he says. “Occasionally I have tough students. Sometimes you have to have the wisdom of Solomon. You have to be diplomatic.”

Oddo walks with a cane. He has bright blue eyes, no glasses and good hearing. He says he doesn’t know why other people don’t work in their 80s.

“I’m addicted to work. I’m 87 years old, and I’m still paying taxes,” he says. “Sometimes the kids ask me, ‘When are you going to retire?’ and I say, ‘That’s not in my vocabulary.’ ”

Solving the world’s problems, over lunch: John Adams

John Adams cooks lunch every day at his store, Adams Paint Center, where he holds court with longtime friends.

At 79, John Adams could comfortably retire from Adams Paint Center, the store at Northwest Highway and Abrams he (and before him, his father) has owned and operated for decades, but he’s having too much fun. He arrives at the shop about 7:30 each morning. He works for a few hours

framing art and photography, which is a significant part of the paint store’s business, but by 10:30 a.m., he usually has prepared lunch/brunch for 4-8 people — maybe sandwiches, soup, meatloaf or chicken. Unfailingly, a small crowd will gather at about noon to break bread in the back room.

“You see — they are not just my customers. They are my friends,” Adams says.

Leah Ekmark, whose artist-husband Fred is Adams’ longtime framing customer, says the lunchtime gatherings are remarkable. “You will find a variety of people gathered around his weathered table — cops, judges and other city officials, a retired horse jockey all the way down to your ordinary contractors. It’s a colorful crew.”

Among the attendees the days we visited was retired letter carrier Dick Barber, pro golfer Rives McBee, and Judge Ken Blackington from Mesquite. Conversation is as varied as the company but, Barber says, “This table has solved many of the world’s problems.”

An interesting, ever-changing and low-stress workload and stimulating friendships give Adams a reason to “get going each morning,” but he didn’t arrive at his golden years without having lived well all along.

Adams left high school to become a Marine, and he trained pilots during WWII. He has owned six Harley Davidson motorcycles. He has two Yamaha motorcycles now and recounts an accident in which he survived sliding along Northwest Highway after a car forced him to lose control of the bike.

“I got a ticket for failure to control my vehicle,” he says, “but I had a buddy on the force who helped take care of that.”

Adams and his wife did a stint on their farm in Nevada, Texas, raising racehorses, and they enjoyed some success, especially with one thoroughbred named Red Sun, a horse that Adams says “nearly paid for the farm.” There was also Ice Cool, Adams Aries, Lord Thomas (named for Adams’ dad), Come Rain or Shine, and Beau Bidder. His greatest contribution to society, in his opinion, is his involvement with Scottish Rite Masonry.

“Masonry takes a good man and makes him better. That’s how it was explained to me,” Adams says.

“When I was a young man living in Vickery — I was pretty mean back then — there were these few men who were very nice and polite and one day I asked them, ‘Why are you so nice?’ and they said, ‘We are Masons,’ and I said, ‘How do I become one?’ and they said, ‘You just did.’ After that, I got nicer.”

The Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children, which has treated more than 200,000 children free of charge since its inception in the 1920s, is one of the organization’s “pet projects,” Adams says.

Aside from the time on the ranch, Adams has spent his life in Dallas. He learned to swim in a lake where the Village Apartments are now located. He remembers the WWII POW camp at White Rock Lake and the skeleton recovered during the lake’s 1953 dredging. He’ll tell tales on acquaintances, including district attorneys, judges and mayors (“Henry Wade and Jack Evans were honest men,” Adams says. “I can’t say that for many of them”). He’ll regale his tablemates with stories about well-known friends, including Keller’s burgers’ Jack Keller and Campisi’s Egyptian Restaurant’s Joe Campisi — “he was the number one guy,” Adams says of Campisi. Without specificity, and with a raised brow and a wink, Adams notes the well-circulated rumors of Campisi’s mafia ties.

Adams, despite recent heart problems, still plays golf regularly (did we mention he was a good golfer? “Wasn’t anyone who could out-drive me back in the day,” Adams says). In fact, the day after we met Adams, he played in a charity tournament. He says he’s having a little trouble getting around, but that the event benefits impaired and in-need kids — his soft spot.

The Trigger show: Margaret Butler

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zwu-eQmPsew[/youtube]Margaret Butler pulls aside a makeshift closet door in her classroom at St. John’s Episcopal School, revealing clothing racks stuffed with costumes.

When students walk into Mrs. Butler’s room, they could be entering an interpretation of mountains in Iraq or a Shakespearean set. Every day is different in Mrs. Butler’s class.

She teaches literature to sixth graders, and the novels they read always have to do with social studies. Costumes, puppets, funny hats, re-enactments and skits are the norm. The desks are never in the same formation from one day to the next.

In the hallway, above her classroom door, is a neon “Open” sign of the type that might be in a convenience store.

“We’re open to what these young people want to know and what they want to do,” she says. “It works.”

Butler is 72, and she gained the nickname “Trigger” in 1952 during a summer at Camp Longhorn in Burnet, Texas, where she tacked a picture of Roy Rogers’ horse near her bunk. The name kept following her until she ultimately embraced it. It fits, too. It’s cute, inviting and totally unintimidating. Kids are at ease around her, even, and especially, sixth-graders.

Trigger pulls one of them into the interview, a blue-eyed boy with brown hair and freckles named Carter Elliot.

“All the teachers here are completely amazing,” he says, after shaking hands. “It’s really fun being a sixth-grader.”

Wait. What? It’s really fun being a sixth-grader?

It’s fun when, as a sixth-grader, a kid walks into the classroom to find plastic building blocks in his way. He must traverse them while water splashes him and recorded gunfire plays from a boom box. For a moment, he is on a 10-inch-wide ledge on the side of the Zagros Mountains, risking life for freedom.

It’s just like what happens in the novel the class is reading, Kiss the Dust, about girls in 1980s Iran and Iraq.

All the world’s a stage, and Butler’s classroom is no exception. She also teaches speech, where eighth-graders learn how to groom and prepare for interviews and public speaking. It readies them for private high school admissions processes, which often involve interviews. When it’s time for speech, Butler’s classroom becomes an office with a receptionist, where students must check in and wait for their interviews. A few weeks earlier, it had been a fashion runway for them to strut their business-appropriate clothes.

On one wall of Butler’s classroom is a collage of faces, pictures of every single student she has had during the past 21 years at St. John’s. She remembers all of their names, and she keeps in touch with many of them.

“I want that spirit, a part of them, to stay right here,” she says. “We’re still connected.”

Butler’s children and grandchildren live in Alabama. Every spring, she asks herself whether this is the year she should retire. So far, the answer hasn’t changed.

“As long as I have gifts to offer, I would like to do that,” she says.

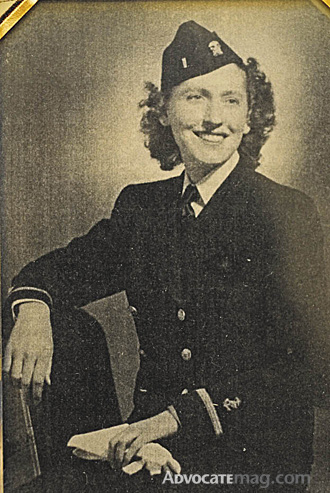

92-year-old miracle: Bernice Press

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4orABsUhEY[/youtube]Anyone who has ever said, “I am too old for that” needs to meet Bernice Press, a 92-year-old miracle. An encounter with Press is a wake-up call after which one can’t help but realize that before him or her lies a vast amount of possibility.

I am greeted in the lobby of C.C. Young’s Asbury building by an upright, smiling woman with a firm handshake and a strong voice.

“Hi, I’m Bernice,” she says.

Her cropped hair is pure white. An aura of color surrounds her — perhaps it’s the crisp blue blouse, matching watch and earrings, or the hint of rose on her lips and cheeks, or maybe it’s something less tangible. At a brisk pace, Press leads me to her first-floor apartment. She says she’s Bernice Press, but the Bernice Press I came to meet is 92 years old. Can this really be Bernice Press?

The coffee table scrapbook filled with honors, magazine articles and photos from a past life as a WWII-era nurse and an entrepreneur who, with her husband, started the country’s first laundromat prove she is who she claims to be.

What’s her secret? For one, each morning she stretches, showers, exercises and dresses for success.

“Every day, I am prepared for a date,” she says. Dry wit drives much of her dialogue.

She stays active during most mornings, doing various volunteer activities, and after lunch she relaxes and plays video games on her bejeweled iPhone.

“I’ve always been a curious person. Always wanted to do more, learn more, keep busy,” she says. Also, her mother lived to be 103, so maybe it’s in the genes, she adds.

When she was in her late 70s and had recently moved into C.C. Young (where her mother also lived), she began putting together new resident welcome bags for patients entering the health center.

She knew firsthand that being in the hospital was “the pits,” and the gifts seemed to lift spirits.

Shortly after this, the center opened a new wing and the number of patients jumped from 10 to 26. It is typical, she says, that a job she has taken on becomes bigger than expected. Good thing she doesn’t let large tasks deter her. These days, the staff at C.C. Young helps out with the welcome bags. When she decided to recognize war veterans living at C.C. Young, it also turned into a big job. Every November, you’ll find Press lining the hallway with photographs and stories of the more than 100 veterans (and counting) who are her neighbors.

The other residents call Press “Mrs. C.C. Young,” staffer Cameron Hernholm says. “Bernice has more energy and volunteers more hours of service than a teenage Boy Scout. She’s a miracle who seems to have found the fountain of youth.”

Because there is so much to do, Press says age 75 is the perfect age to move to a retirement community.

“Don’t wait until you’re old,” she says.

Since she arrived, Hernholm says Press founded the first support group for adult children of aging parents. She also facilitates the Alzheimer support group; she was on C.C. Young’s national championship Wii Bowling team; she traveled last year to Washington, D.C., as the one female among a group of WWII vets; she is the C.C. Young Auxilliary Club’s vice president. Off campus, she volunteers at the Dallas Bethlehem Center, a non-profit that helps South Dallas children.

In the 1930s, Press received a music scholarship and played the baritone during college. Her mom encouraged nursing school.

It’s no surprise that Press spent her early years as a nurse, loved for her bedside manner.

“Touching, listening, talking,” she says, is as important as the medical treatment. One of her patients, Leonard Press, married her. He was an entrepreneur, and in the 1940s, the pair opened up Leonard’s Self Serve Laundry Mat, the first of its kind, in Los Angeles. Years later, they also owned a country and western bar in East Texas, The Hitching Post.

Along the way, they adopted a Bolivian child, Carol, who recently celebrated her 60th birthday.

Carol is to thank for her mother’s aforementioned bling. “She goes to the shops along Harry Hines and buys earrings and watches,” Press says.

She opens a drawer containing dozens of colorful wristwatches. “I have one for every outfit.”