Photography by Haley Hill

La Casita owner Maricsa Trejo knows what it means to

be pushed.

Her career began in El Centro College’s class kitchens. The path has taken her to fine dining kitchens in New York and bakeries in Oregon. She’s gotten there and back by being pushed by her family, colleagues, mentors, fiery chefs and, of course, herself.

Trejo is a highly-skilled pastry chef, business owner and James Beard award finalist. La Casita’s name frequently pops up in local publications’ “Best Of” lists. She recently opened a second La Casita Coffee location in the Lake Highlands area, and plans to debut a third later this month in Uptown. After months of wrangling with code compliance, vendors and contractors, it would be understandable for her to take a break and catch her breath.

But oddly enough, she’s still talking about expansion.

She’s still pushing.

Pancakes

Trejo was born in Mesquite as the daughter of immigrants from Mexico. Her mother arrived in her early 20s, and hadn’t received much formal education. Even though she had trouble reading herself, she still would take Trejo and her siblings to the library on Saturdays.

Her father, Alfredo, worked six days a week.

“I’d miss him,” Trejo says. “So sometimes I’d go with him on Saturdays, when he worked, I’d do my homework. He’s a plumber, so he does all the houses that aren’t built yet, he does all the plumbing for those, so he would be out in the heat. And I was like, if my dad can do it, I can go out there and do my homework.”

She says she tends to keep those long days in the Texas heat in the back of her mind when she’s pushing herself to finish laminating in the back of her air-conditioned bakery.

Alfredo may have worked constantly, but the seventh day was a special occasion. On Sunday mornings, he got the time off from work some would use to rest on a reclining chair and watch TV. Instead, he saw it as an opportunity to share a meal with his family.

“They [Trejo’s parents] didn’t grow up eating pancakes as kids, my dad learned how to make pancakes on his own,” Trejo says. “He would make pancakes and fried eggs and bacon and all these things for us on Sundays because he wanted to be part of us.”

She knows the sacrifices her parents made in coming to the U.S. paved the way for her career, and says she respects their resilience “so much” in a “country that has very little love for people coming over here.”

“I’m doing it for myself and my husband, because we started this business together, but I’m also doing it for them. Because [when] I just became a cook, I’m like, ‘I promise I’m gonna do something big with it.’”

The Pastry Hater

Food has been a fascination from an early age, although her first interests were in art and music. She grew up surrounded by Mexican cuisine, but her “super authentic” experiences at her Argentine godmother’s house helped her realize she was interested in cooking, not flute playing.

“My mom would get jealous, because I’d be like ‘(She) is so good at cooking, and she does this and that.’” she says. “But my interest became, basically going from art and music, to, for some reason, cooking.”

She went on to enroll at El Centro College. Trejo didn’t want to commit to full-time culinary school before testing the waters, so she took basic cooking classes alongside the core curriculum.

Her least favorite class may come as a surprise.

“I hated pastry really,” she says. “I went to school and, my first pastry class, I don’t know if it was my teacher. She was a good teacher. You could just tell she just did not want to be there.”

The art of pastry was lost on her. Trejo liked cooking. She relished the flash of the pan, and the ability to improvise on the fly to rectify mistakes. With pastry, instead of seeing beautiful manifestations of hours of labor, she saw tediously time-consuming fragile eggshells that presented 100 opportunities for miscalculation and ruin.

But as she progressed through her training, pastry started to make more and more sense.

“When I got into pastry, I realized I had all these weird ideas for pastries,” she says. “And like cooking, I guess you could say I never had an original idea. And I was like, ‘What am I?’”

The pastry hater slowly turned into a pastry chef.

Trejo left El Centro in favor of the college of hard knocks. She found a job at the Omni Hotel, and progressed from the banquet kitchen to the Texas Spice garde manger. Wanting to learn “as much as possible,” she volunteered to help prep for pastry in her spare time.

“I met one of my best friends there,” she says. “Her name is Lucia. She has a pastry place. She has a patisserie in Puerto Rico — I actually visited her two weeks ago — She was like ‘If you want to do this, dude, if you’re getting pressure to do this, don’t do it.’ But I was like, ‘No, I actually really like this.’ So I fell in love with pastry.”

Photography by Haley Hill

“No one is ever going to hire you”

After leaving the Omni, she took a job in Oak Lawn working for an unnamed chef. The environment was not what she’d hoped.

“There’s no reason to treat anybody in any industry anywhere without respect, whether you’re male or female,” Trejo says. “And I was like, this is just not where I want to be anymore.”

She quit mid-shift after a particularly nasty interaction with the chef. On her way out, with announced plans to go to the Big Apple, the chef told her that “no one is ever going to hire you in New York.”

She got hired — in New York — to work at restaurant legend Tom Colicchio’s Collichio and Sons.

“He actually went there one of the nights and hung out and cooked with us,” she says. “And I was like ‘oh my god, I can’t believe I’m in the presence of Tom Collichio.’ It was so cool.”

After New York, she took a job in Oregon working as an overnight bread baker for Grand Central Bakery. She says she traveled there, alongside her now-husband, Alex, to become more well-rounded as a baker, which she figured would benefit her when she opened her own shop one day.

The chain operates similar to La Casita, with an array of locations selling house-made pastries and baked goods.

“I learned how to work with those big machines and I learned what it takes to have a big company like that … they’re huge in Oregon. They provide a ton of places with bread, and we do that now too.”

After a year in Oregon, Trejo and Alex returned home. She missed her family. She’d traveled across the country for two years, first in New York, then in Oregon, gaining valuable experience along the way.

Sitting on a stool in her Richardson bakeshop, Trejo remembers the Oak Lawn chef’s words a little more gently than she probably did at the time.

“He made me realize that, funny enough, I’ve always felt what he said to me about myself,” she says. “And then I went to New York, and I proved him and myself wrong.”

Burger Buns

Alex is an accomplished chef in his own right, so he and Trejo consulted for Small Brew Pub in Oak Cliff upon their return. The pair helped craft a new, elevated menu, which Trejo says was soon supplanted by burgers and fries.

The urge to create her own business started to take hold. She hounded Alex with thoughts about a potential bakeshop until he’d had enough.

“He was like ‘I love you, Maricsa, but you either have to stop talking about this dream or do it. You can’t do both,’” she says. “I can’t spend the rest of my life just hearing my wife be like, ‘I should have been. I should have done it,’ he said, ‘Just do it. Just try it.’ And he pushed me. And I have never been pushed that hard before. And I was like, ‘How rude. He’s so rude. How dare he say this shit?’ And I was like, ‘You know what? He’s right though.’”

While she left Small Brew Pub’s employ, she didn’t leave its kitchen. She registered La Casita Bakeshop — named in honor of her Hispanic heritage — as a DBA and began selling her pastries to a few coffee shops around town. Small Brewpub’s kitchen was rented as a baking venue in exchange for burger buns.

But, working mostly by herself, the hours were long, and she needed help.

Luckily, Alex was getting tired of bar food. So, he left the pub and joined Trejo in the endeavor. La Casita was officially launched soon after in 2017. The pair opened the doors of the first Richardson Bakeshop in 2020.

Half Price Books

Four years later, the La Casita brand employs close to 100 people across five locations. La Casita Bakeshop, the brand’s flagship store in Richardson, serves artisanal cruffins alongside a full brunch menu. Trejo’s event venue, La Casita Garden, is open for rentals with a lengthy catering menu available.

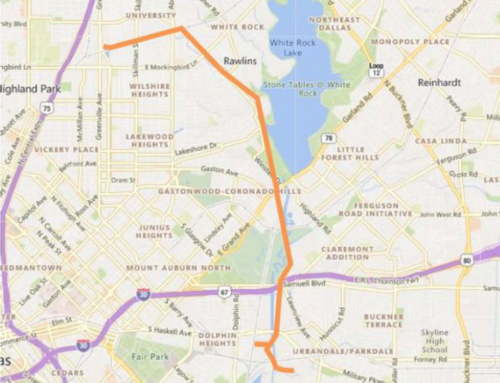

There are two coffee shops, one in Rowlett and another on Northwest Highway, where she recently opened up a second La Casita Coffee location in Half Price Books. A self-described “book nerd,” she says the location is perfect.

“I used to go to the library with my mom,” Trejo says. “And even in Rowlett, we’re near a library, and now we’re inside Half Price Books, and I’m like, what other library places can I go into?”

The Half Price Books location, which opened in August, sells pastries baked at the flagship bakeshop and coffee from a program developed by La Casita’s third partner, Brianna Short. Sandwiches such as the Tikka Marsala, a fried chicken breast covered in house-made Tikka Masala sauce and served with a cucumber raita, pickled red onion and fresh cilantro, all come served on La Casita’s house-baked bread.

A full brunch menu is on its way, and Trejo says she plans to eventually transform the space into a tiki bar with dinner service at night. An old colleague from Small Brewpub has been brought on to develop a cocktail list, and an eclectic dinner menu has been planned.

“It’s gonna be like a mix of Pacific Island food,” Trejo says. “Asian food, Vietnamese, Korean and Mexican food.”

Community

One of Trejo’s points of emphasis is taking care of her employees, she says. She uses the word community to describe the culture she’s tried to create.

“It’s so cool to have a community … we’re here at work all the time, so for me and my husband and our employees, it’s important to care about each other,” Trejo says. “They don’t have to love each other. But just caring about when someone leaves here, where are they going home to, or who are they going home to? That matters a lot to us.”

La Casita offers health insurance to full-time employees, although that may have to do less with community and more about keeping her workforce healthy, she admits.

Trejo says that her “community” is one of the biggest contributors to La Casita’s recent success, and that she’s created a collaborative atmosphere where employees are welcome to have thoughts on the menu.

“Weirdly enough, my employees push me,” Trejo says. “I can see in their eyes. They’re like, ‘I want to do these new things.’”

Pushing forward

La Casita Coffee is expected to open another location in Uptown this month, bringing the total of La Casita locations to six across Dallas, Richardson, Rowlett and Frisco. She says that she will continue to look for “smart” expansion opportunities, and that she does not want growth to compromise quality.

It doesn’t seem like she plans on stopping anytime soon.

“My dream for us as a bakery is to be everybody’s neighborhood bakery. And it’s hard to do that when you’re just in one neighborhood.”

La Casita Coffee, 5801 E NW Highway, 469.899.0969