Forty years ago, the Dallas Independent School District forcibly desegregated its schools. Many involved in the painful, frustrating and necessary process, which lasted more than three decades, are still around to share their stories.

As told to Keri Mitchell • Photos by Can Türkyilmaz, Benjamin Hager & Madeline Stevens

Protest scene 1 of 3: In protest of the Dallas school board’s consideration to close Woodrow and J.L. Long, students argue that their schools are already integrated, in this Sept. 7, 1975, photo from the collections of the Texas/Dallas History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library.

Until 40 years ago this fall, black students living in Dallas were relegated to a small portion of the city’s schools. The rest were reserved for white students. Even though the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown vs. Board of Education lawsuit outlawed segregation by race 17 years earlier, Dallas public schools hadn’t fully heard the message.

In 1971, however, after plenty of lip-service but little concrete action from public school administrators, a federal judge forced black and white students to integrate through busing. It didn’t take long for the fallout to begin. Lives were disrupted. Students and parents threatened each other. Families both black and white fled their neighborhoods for suburban and private schools. This story isn’t an attempt to analyze that history-altering process. Instead, 40 years after desegregation began, key neighborhood residents involved in the process look back on those years and tell us in their own words what the changes meant to them, our neighborhood and our city.

ED CLOUTMAN was beginning his career as an attorney in Dallas when Sam Tasby walked into his office in 1970 saying he wanted his two sons to be allowed to attend their neighborhood school. Cloutman filed the lawsuit and spent the next 33 years defending the cause of Tasby and all minority families and children in the Dallas school district. Cloutman lives in the Lakewood area and still practices law, spending most of his time representing labor cases.

Cloutman: I grew up in Louisiana, and I never attended a school with African American children in it until I got to college. It was not a big deal where I grew up, just one of those things that was there. My parents were reasonably progressive for the time. There was lots of boisterous language about the early civil rights activists who would ride the busses or sit at the lunch counter, and mother and daddy would say, ‘Look, this is going to take a while, and there will be a lot of things said you shouldn’t believe wholeheartedly, and it will be awhile before our Negro friends are allowed to participate in the things we do, but it’s coming, so you should never talk badly about these friends.’ And there wasn’t any talk in my house for fear of my mother and my daddy. Those were unusual times. Different now, thank god.

ROBERT H. THOMAS began representing the Dallas school district in the desegregation case in 1980, when the original attorney had to resign due to health issues. Thomas and his wife, Gail — currently the CEO of the Trinity Trust Foundation — live in Dallas, and he is a partner emeritus at Strasburger law firm.

Thomas: The first case was Brown v. Topeka and was handed down in about 1954. The Supreme Court said segregated public schools are unconstitutional. And nothing happened, actually. It just fell on deaf ears around the country. And then a couple of years later, the Supreme Court handed down another decision that said, “We really mean it. You’ve got to desegregate the schools and do it with all deliberate speed.” Well, speed is in the eye of the beholder.

JAN SANDERS is the widow of Barefoot Sanders, the federal judge who took over the desegregation court case in 1981. Sanders still lives in Dallas and remains active in the community.

Sanders: The thing was that we had Jim Crow laws that were discriminatory, and from those laws we have the heritage — the culture of discrimination that affirmed those laws. People tolerated that this is just the way we live together — we have colored water fountains and white water fountains, we have colored waiting rooms and white waiting rooms, we have black schools and white schools. These were the cultures that emerged from the law. The culture might change but the law is static, so that’s what had to change in the courts. Some people have said, well, the community finally changed enough to accept this change, but the law part of it was very important. We are a nation of laws. People’s whims and prejudices come and go with the wind. They’re not as established as the law is, and the way our government is set up is to respect the law.

BOB JOHNSTON is an Adamson High School graduate, class of ’59, and taught at the school from 1962 to 1969. In 1970 he began working in the Dallas ISD communications department, and later became the board secretary for 17 years then special assistant to the superintendent from 1998 to 2000. He lives near White Rock Lake.

Johnston: We had had a couple of court orders before 1971. One in 1955 — it wasn’t any big thing; it didn’t contain a lot of changes — and then a stair-step order in the late ’60s where we were to desegregate grade by grade beginning with the first grade and doing a grade a year. Then they came back and changed that, and we kept the stair-step, but it started in the high schools. Then they filed a new suit, and that brought about the big order in ’71.

African Americans and the law

Cloutman: Mr. Tasby walked into my office in West Dallas in summer of ’70. It was late summer, and kids had gone back to school. His kids, Eddie Mitchell Tasby and Phillip Wayne Tasby, were then being assigned to Sequoyah Middle School and Pinkston High School, and he thought it was not fair because there were nearer schools to his home, and no buses available — they had to ride the city bus at his expense. He was a working guy. We started talking to other people, and by October, we had filed the lawsuit.

Thomas: You know the difference between state and federal courts? People elect judges in the state courts, and judges in federal courts are appointed for a lifetime. That’s a major difference. So if a judge wants to get reelected, he’s not going to say, “We’re going to desegregate schools.” There were a few in California who did, but for the most part, certainly in the South, the state court judges said, “Huh-uh, can’t be done.” They would have been voted out the next election. So it wasn’t too long until the liberal lawyers figured out that the only place to force desegregation was in the federal courts.

Cloutman: We were real sure we were going to win the initial round. The schools were well out of compliance with what the Supreme Court had said at the time. A huge round of cases were decided by the Supreme Court the year of our trial, and they were sort of the benchmarks: “You’ve got to do this, and you’ve got to do it now. You can’t wait any longer.”

Thomas: The Tasby case was filed in Judge Mac Taylor’s court, and he didn’t know what to do with it. You won’t believe this, but the school district says, “Well, if we want to have these students go to school with each other, why don’t we install televisions in each classroom so schools in South Dallas can hook up with North Dallas classrooms, and they can conduct desegregation that way?” Is that not classy?

Cloutman: It was $25 million just to install the cameras and the screens. Today that’d be closer to a half a billion, given inflation. We got that stopped in about a week. The plan Judge Taylor [later] adopted involved a fair amount of busing for high school and middle school students and was sending some of the poorest kids from South Dallas and West Dallas into North Dallas schools where the economies were like night and day. They had more money, they had after-school programs — it was sort of an invasion of sacred space by kids who were so poor and were not made to feel welcome.

Protest scene 2 of 3: In protest of the Dallas school board’s consideration to close Woodrow and J.L. Long, students argue that their schools are already integrated, in this Sept. 7, 1975, photo from the collections of the Texas/Dallas History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library.

Johnston: When busing started, the superintendent at the time, Nolan Estes, had all of the central office administrators get their school bus driver’s licenses, and the first big school day of the busing order, he drove a school bus himself. [Estes] had hired monitors who rode the buses with the kids from South Dallas and then worked at the schools when they got out there so the kids knew somebody from their neighborhood. Dr. Estes also integrated leadership at the schools. He brought in principals and assistant principals of other ethnicities than all white, so that helped facilitate desegregation, too. One reason we used so many monitors was because there were lots of folks in the black community who didn’t like the idea of their kids being bused out. They wanted integration, but they feared what would happen at the end of that bus ride, or whether or not they would get on the bus and go out to the school only to be put in a separate class. And that happened sometimes until somebody would find out about it and straighten it out.

Cloutman: It was a horrible atmosphere for kids of all colors because it was organized mayhem in schools. The atmospheres were allowed by principals to fester. It was sort of like, “You want integration? I’ll show you integration.” Kids at Hillcrest, kids at Spruce were getting into constant fights. “This is the right thing; we’re going to do it,” was not something you heard from teachers and principals. That sort of thing happened for four years, and Dallas was growing then, and people were basically being told, “Don’t locate in the Dallas ISD because they have busing.” And it worked. It wasn’t so much we had white flight, but no white in-migration, and as white kids graduated, there was nobody to replace them. People with school-age children were not locating here.

Sanders: Some of the very respected African American leaders were for busing, and at the end of it, they were against it. Why should these kids ride all the way across town to go to school with kids down the street?

Cloutman: The plan that was on the ground just wasn’t all that good, and that’s why we had appealed all of it. You argue these cases to three different judges, and one of the judges had gotten rather ill and just wouldn’t decide anything, so the case was just sitting [in appeals] from 1971 to 1975 — four school years — and that led to a lot of uncertainty and led to a lot of people leaving the district.

Thomas: One of the things that made it difficult was that we had such a large African-American population south of Interstate 30 and none north of Interstate 30, so it made it very difficult to mix bodies or teachers or anything without crossing the expressway. That’s a historical fact and a historical problem we had with desegregation because of the long distance between blacks and whites.

Cloutman: I was surprised by the amount of resistance. You read about it in a lot of places, but it seemed to dissipate, even in the Deep South. We were still dealing with it 10 years in. I guess you just can’t underestimate the racism in some people’s hearts. It’s just a hard thing to measure.

Woodrow and Long

In 1966, while most Dallas schools remained segregated, J.L. Long Middle School, then an eighth- and ninth-grade junior high, began welcoming black students. Long and Woodrow alums from the late ’60s and ’70s still refer to the schools as being “naturally” integrated or desegregated, and the federal courts agreed with that assessment in their rulings.

DENNIS ROE is a ’71 Woodrow graduate who lives in Dallas and is the secretary of the Woodrow Wilson High School Alumni Association.

Roe: When I started high school in 10th-grade, that was my first real experience with desegregation, as far as going to school with African-Americans. I lived in the Buckner Terrace area off St. Francis, Jim Miller and I-30. It was 100 percent white. The blacks we went to school with at Woodrow basically came in from a small area between Fair Park and Interstate 30, which was Highway 67 back then. Woodrow was naturally integrated, so we never had busing there.

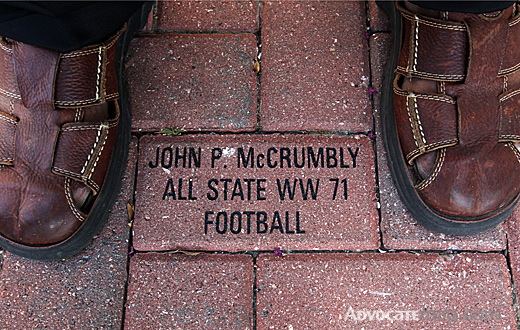

[Integration] was a big deal, and it wasn’t. To a lot of the kids, it didn’t really matter. I know some parents who moved out of our neighborhood and into the Bryan Adams [High School] attendance zone. There were parents who were very redneck and very racist who said, “I don’t want my kids to go to school with blacks.” It was a short-term solution. They eventually had to move out of town if they wanted to avoid it.A lot of people adopted [integration] because of one person — a fellow by the name of John Paul McCrumbly. He lived on Gurley, a little street that runs north-south from I-30 to Fair Park. He still lives there today.

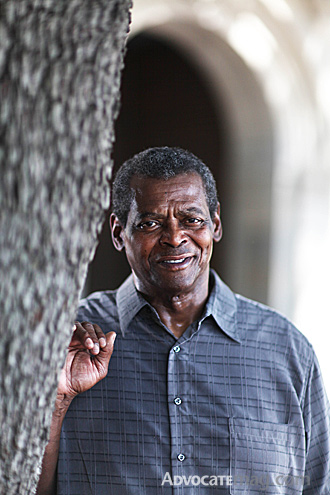

JEFF PATTON attended Lipscomb Elementary while JOHN PAUL McCRUMBLY was at O.M. Roberts. They both found themselves at J.L. Long Junior High in fall 1966 and wound up being inseparable friends. The ’71 Woodrow graduates still live in the neighborhood and remain close friends.

Patton: Me and John Paul, we went to J.L. Long the year they started integration in Dallas. I went to Lipscomb Elementary. Lakewood Elementary is the cliquish little elementary school to go to, so if you didn’t go to Lakewood, they don’t know you at Long. So me and John Paul, we didn’t know anyone, so we just became friends.

McCrumbly: When we got started, we just were kids going into a new environment. We didn’t have it so hard like some of the others. We didn’t have a lot of fights or that kind of stuff. There weren’t but 27 blacks at the time, so we got along pretty well. We just kind of blended in.

Patton: There was never a minute’s trouble with integration at Long and Woodrow because John Paul was accepted, and John Paul was the sweetest person you’ve ever met. He’s the calmest, the gentlest, and he was the biggest human being anyone had ever seen. Here we are coming into J.L. Long Junior High School, and the big guy in our group may weigh 150 pounds, and John Paul was 220, 6-feet-2-inches and fast as lightning.

Roe: He was so big, nobody could tackle him. He would drag three or four guys over the goal line with him. And because of that one player, the blacks seemed to become very adopted at Long and eventually at Woodrow. At that time, we had only 35-40 blacks across grades 10-12. [John Paul] was sort of the rallying point of the blacks at our school because of his great athleticism — something that had not been seen in our parts, ever. He played on the varsity team his sophomore year, which at that time was unheard of, but he was so good the coach moved him up. I played with John Paul, and we went to playoffs and almost played [the] state [championship]. All the blacks rallied around him, all the coaches loved him, all the players loved him. We didn’t treat him any differently than we treated ourselves. He was a great guy — fun to be around, very articulate and smart.

Patton: John Paul, the reason he didn’t have any trouble was because he was John Paul — just a good human being. And he’s the football hero, and that helps you get accepted. And then the other big part was that Joe Geary, a gigantically prominent lawyer in Dallas [and former city councilman], and Henry Wade, the district attorney, had him over at their houses.

McCrumbly: One time, I think I had a funeral to go to in junior high school, but we had a game, and I stayed at Henry Wade’s house. I met Mr. Wade through his wife, Mrs. Wade. We were at a football practice. I didn’t know who the Wades were, then they finally told me what he was. Mr. Wade made sure we all stayed in line. He treated us like we were his sons, just like we were his own children.

Patton: My dad was Dr. Walter H. Patton, he’s an old-time doctor here in East Dallas and was the team doctor for Woodrow for 30 years. He had his office at the corner of Columbia and Abrams. My dad, he was a real unusual person for that day and time because in the ’50s and ’60s, I’m not saying everybody was a racist, but if you weren’t a racist, you kept your mouth shut because the racists were mean and belligerent. My dad, he wouldn’t listen to any of that. We took John Paul to Wilshire Baptist Church — a Southern Baptist church that never had a black person in it, and we sat on the second row.

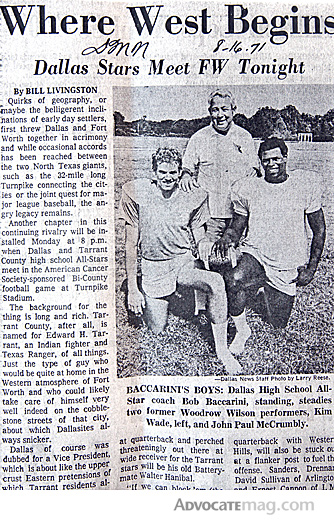

During his years at Woodrow, John Paul McCrumbly played alongside Kim Wade, son of longtime Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade, and spent time at the Wade family farm. This photo is from the Aug. 16, 1971, Dallas Morning News.

After that we went to Lakewood Country Club for dinner. My dad got a three-page letter from Lakewood Country Club saying, “We appreciate your sympathy and empathy, but don’t do it at Lakewood Country Club.” There wasn’t no one who would take John Paul McCrumbly to Lakewood Country Club in 1968 but my father. That was the key — that three major players in the Lakewood area treated him like family. Anytime I went somewhere, John Paul was with me. So they knew if they invited me to a party, John Paul was with me. Because everybody didn’t have the same feelings toward blacks, I guarantee you.

Roe: I’m sure there were kids who had with the attitude of, “I’m not going to deal with them any more than I have to. They sit next to me in class, OK.” It was just too early. It was the first year for some of these kids. You wouldn’t have seen a lot of socializing with the blacks back and forth if it wasn’t for athletics. It was a little different being in class with them. We could tell there were cultural differences and educational differences. We could tell from the clothes they wore it was a different atmosphere they came from. It took a lot of adaptation on both cultures’ part to get used to each other.

McCrumbly: From what we heard about other schools, we thought there was a lot of stuff going on, but it didn’t happen at Woodrow. We all looked after each other. There wasn’t ever no squabbling. We all mixed in real good. Some of the black girls were on the drill team, and one was a majorette [in the band]. We’d go to football games and to the YMCA up the street after the football games — that was the big hangout. We partied and never had no fights or none of that. Jeff Patton and Kim Wade [Henry Wade’s son], they’d come by to pick me up, and we still socialize now.

The Dallas Alliance

While the Tasby lawsuit stalled in the appellate courts, the Dallas Chamber of Commerce in 1974 created the multi-racial Dallas Alliance, which in 1975 spawned a task force charged with creating a plan to desegregate the schools.

CLAIRE CUNNINGHAM was president of the Dallas Council of PTAs in 1975, when she was named to the Dallas Alliance task force. She had three daughters at Lakewood Elementary and J.L. Long, and had served as PTA president of both schools. Two of Cunningham’s daughters, including Cheri Flynn (above, left), wound up graduating from Skyline High School, one of the magnet schools that emerged from desegregation court orders. Flynn now teaches art at Stonewall Jackson Elementary and still lives in the neighborhood. Cunningham lives in The Cloisters subdivision off Mockingbird Lane.

Cunningham: The Dallas Alliance was a fairly powerful group of business people, mostly men. The alliance decided it would be a good idea to see if they could be a friend of the court and come up with a plan. I was named to the task force because I was white, I was a woman, and I represented the PTA. There were six blacks on the task force, and there were seven Latin-Americans and one who was American Indian. Basically, it was a seven, seven, seven ratio. We had books and pages and so forth of what each school looked like. We looked at the demographics and looked at all the possibilities. The task was to try to come up with a plan that everyone would sign off on. It was to try to influence the court to create a plan that the city would buy without riots and as peacefully as possible. There had been situations all over the United States where there were riots. Our concern here was, could we do this and not cause civil unrest that would damage the schools, the city, the business atmosphere — that was high priority. Dallas was a nice place. I liked it. I wanted it to continue to be nice.

Johnston: Dallas really desegregated differently than a lot of cities because it was calm. We never had the riots and standoffs and things like that in other cities, largely because Dr. Estes was a master at getting the community into the schools. He organized the business community and the mayor, and everybody like that understood what disruptions would do to the city and the city’s reputation for business, so they got involved.

Thomas: The city fathers were very, very careful to avoid the rioting and the fighting and everything that occurred in the other cities. We never lost a bond election. Every time, people voted to tax themselves because the city fathers said, “The school district needs this money, and we’re going to have a good integrated school district. We didn’t want an integrated school district, but we’re going to spend the money to do it.” It was a deliberate effort on the part of every councilman and mayor and school board member to work together.

Johnston: Now, we had people show up at school board meetings who complained and picketed and things like that, but it wasn’t like Little Rock where they called out the National Guard and that sort of thing. People remember it mostly through the media and the effect it had on their kids. If they had kids in school while busing was going on, they weren’t too wild about it.

Stephanie Zimmerman helps Bridgette Monique Robinson, a Lakewood Elementary fourth grader, in this 1977 photo from the collections of the Texas/Dallas History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library.

Cunningham: I didn’t want any busing at all, if I could prevent it. And our final plan to leave kindergarten through third-grade in their local schools and only start busing in fourth-grade was a unique plan. It’s obvious what we were trying to do is get parents to start in a school and see what a good school it was. It didn’t work all the way — we had a lot of white flight — but it worked pretty well in Lakewood. People kept their kids in there at least through grade three.

Flynn: That’s why Lakehill [Preparatory School] started. We had friends who said, “We’re not doing that.”

Johnston: That’s really when we saw the first church schools spring up, and a lot of churches started schools or let schools be housed in their facilities. There hadn’t been much of that prior to the time the court order started. The mindset was that the black kids were rough and violent and didn’t behave, and people feared that, even though it basically wasn’t true, but it’s hard to convince somebody.

Flynn: I had left my white elementary of Lakewood and had spent two years at Long, fully integrated. So to be perfectly honest with you, I didn’t see what the big deal was. My younger sister at Lakewood had a different experience. What they did at Lakewood, they didn’t bus kids in, but they bused teachers in. Long and Woodrow didn’t have kids bused in because it was naturally integrated, so it didn’t really have an effect on me.

Cunningham: There was no busing out of Lakewood, just busing into Lakewood.

Flynn: And see, that was the difference — which neighborhoods were being asked to move. That part you wouldn’t get away with now. I don’t think there were any white kids bused to South Oak Cliff High School. You have to remember at the time, whites were the majority in this district.

Cunningham: The purpose of the magnet schools was to try to convince white students to go to these schools that would be integrated by their numbers — a one-third, one-third, one-third — since they were very good schools. That was volunteer busing. Cheri, she went to Skyline because it had just opened up with the magnet schools all there. And then Jill, the middle one, did the same thing when she got out of Long. She wanted to go to Skyline and do music and math. Kim, the youngest one, went to Woodrow from the very beginning as a sophomore. The truth be known, she was a drill team person at Long, so she wanted to do it at Woodrow. You could go to one of the magnet schools that we created and still do your home school stuff, so she would go in the morning to the magnet school and then go back to Woodrow in the afternoon and do the drill team thing. A lot of people didn’t want to give up their home school things, and the magnet had no activities to start with — no clubs yet, no athletics yet — and the reasoning behind magnets was to make it easier for people to move over into what we hoped would be very integrated schools.

Sanders: Our second baby was born the day of Brown v. Board of Education, so then the DISD finally had a magnet program that she went to school at that was brand new 16 or 17 years later. So the deliberate speed was not very speedy in Dallas.

Cunningham: [The plan] didn’t totally succeed. There still were schools where, even despite the integration orders, some of the teachers weren’t that qualified initially. [Black teachers] were transferred to try to integrate the facilities, and we discovered why some of the schools they were in were poor schools because they really weren’t very qualified. That was one of the early moves that happened at Lakewood, and Jill still fusses. She was in seventh grade when the court order went in, and she had, in one of her classes, just a horrible teacher. Fortunately, I taught English and I could back it up, but a lot of people missed out.

As I sat on that task force, I spent many a night thinking selfishly, “How is this going to affect Long, Lakewood, Woodrow?” I worried about it a lot. I remember making a comment that I felt like I had been through labor negotiations or something every time I came home from one of those task force meetings because the negotiations were very tricky. The interesting part of that task force is that the original chairman, Jack Lowe [Sr.], had the concept that we should never vote on anything, that we ought to talk until we came to a consensus. That was sometimes difficult, but it kept us from dividing down lines all the time. My comment has always been no one in the room got everything they wanted, and they got a lot of stuff they didn’t want, but it was something we could all agree on.

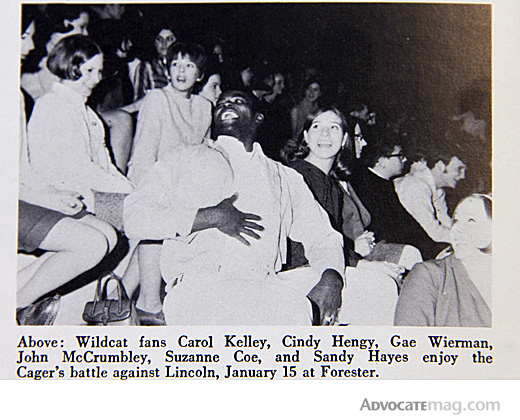

John Paul McCrumbly easily mixes in the Woodrow Wilson High School social crowd in this photo from the 1968-69 yearbook.

Integration in the 1980s

Though Judge Taylor adopted the task force’s plan in 1976, the case was far from over.

Thomas: I started in about 1980. The lawyer [before me] representing the Dallas public schools, his name was Warren Whitham, and he was a staunch segregationist. He wasn’t going to give up and let the judge tell his district what to do, and he just fought and fought and fought, and he had a heart attack, and his doctor told him, “Warren, you’ve got to get rid of this case. This case is going to kill you.”

I was president of the Dallas Bar Association in 1978, and we bought the Belo Mansion on 2101 Ross Avenue. It was an empty big home that had been a funeral home, but the lawyers of Dallas thought it would be neat to lease it as our headquarters.

By 1980, it was finished, and one of my partners said, “Bud, you owe us a lot of time. You’ve had a lot of time off; you’ve really got to get to work on something.”

And I said, “Anything you need done, I’m willing.” And about a month later he called me into his office and says, “Warren Whitham has had a heart attack, and they’ve asked our firm if we can furnish a lawyer to handle the case, and I think you’re the right guy for the job.” And I said, “Oh crap.”

I went to see Warren Whitham at his home, and I said, “Warren, I’m Bob Thomas, and I’m going to try to take your place in the desegregation case.” And he says, “Alright but let me tell you this: Fight, fight, fight (coughing), fight …” and his wife comes in, and says, “I’m sorry, Mr. Thomas, but you’ll have to leave.”

I had just met the superintendent of schools — his name was Linus Wright, the new superintendent from Houston — and I walked out of Warren Whitham’s home and went to the nearest 7-Eleven and used a pay phone to call the superintendent, and said, “I need to come talk to you.”

And I told him the story of meeting with Mr. Whitham in his home, and said, “Is that what you want me to do? Do you want me to fight, fight, fight?”

And he said, “I’m so glad you asked me this question. No. Desegregation is coming. It’s here. It’s 1980, and we were told in 1954 that it had to be done. We want it done, but we want it done with a degree of sensitivity. We don’t want to alienate our employees, and the constituents and taxpayers of Dallas. We have to do this in an orderly manner where we don’t lose students, we don’t lose teachers, and we build up a fine desegregated school system.”

And so that’s what I did for 23 years.

Cloutman: A friend of mine was doing this in Mississippi, and I wrote him [in 1970] and told him we were doing it, and he said, ‘Well, great. How long do you think it’s going to take?’ I thought, trial by summer, an appeal by next year, should be done in five years. Wrong. 33 years — 1970-2003. Bob Thomas and I were friends to the end in this case, mostly because we learned it was easier to get along than fuss at the courthouses.

Thomas: Barefoot Sanders came in just a little after I did because Judge Taylor was in ill health, and he had to retire. Judge Taylor called a meeting of all the federal judges in his office, and he said, “Gentlemen, I want one of you judges to take it over for me. Which one of you wants to do it?” Silence. “OK, tell you what we’re going to do.” He took six slips of paper with the names of the six judges in the room and put them in his hat and said, “I’m going to pull a name out of the hat, and you’re the new judge in the desegregation case.” And he pulls out the name and says, “Barefoot Sanders.”

Sanders: The truth of it was that none of the judges wanted it. Barefoot was, I can’t say delighted, but I would say eager to take it on. He saw it as an opportunity and went after it. Barefoot was very proud of his role in this case because he was born and raised in Dallas and educated in the public schools and saw the importance of individual rights. He had served in Washington to pass the voting rights act of 1965; he was in the Department of Justice at the time.

Cloutman: When we started this, we truly had two school systems in town. The black kids were going to school in inferior buildings with three-editions-ago schoolbooks.

Sanders: There in South Dallas they had bought the property of an unsuccessful shopping mall on the east side of freeway. It was just always fraught with problems and leaks because it wasn’t built as a school. I remember that they didn’t have a fence along the freeway where the playground was, and if a ball or something went off the field they could step into a freeway, so Barefoot just insisted they build a fence. They kept saying they would build it, they would build it. It wasn’t done until he insisted on it, and that was frustrating about the case. The resistance was like taking a big locomotive and turning it around in another direction.

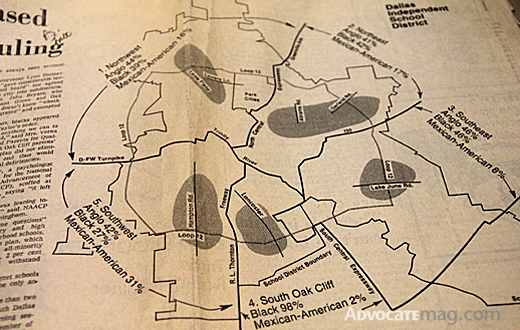

This Dallas Morning News map from the March 11, 1976, newspaper shows the racial makeup of five areas in Dallas ISD in an article examining the latest busing plan.

Thomas: We had a bunch of black students in shabby buildings. I mean really crummy buildings. They were colored schools, and they had not been kept up. The roof leaked, and it was cold, and the campus wasn’t big enough, so the court said to supervise the buildings.

Sanders: A lot of people in the community simply distilled the integration-segregation issue with students sitting in the classroom, and certainly that was a huge, important part of it, but that wasn’t all of it. A lot of the inequities in the Dallas ISD had to do with staff, facilities, boundaries. They were the vestiges of the Jim Crow laws, and so there were a lot of facets for him as the judge to get right.

Johnston: In many cities, they were just body mixing. All of our orders were educational orders. Black kids at that time had poor test scores as it related to the white kids, and the goal in getting them together was to provide a quality education for all and raise the test scores as a result. The feeling we tried to get across to the community was the education element was important and necessary; the body mixing was an effect.

Thomas: It finally dawned on the blacks, “We don’t want to ride the bus, either. Why don’t we just have better schools in our neighborhood?” So slowly the idea began to crystallize that maybe it’s better to have good schools than integrated schools. They would rather have more money spent on those black schools and have good teachers than ride the bus to someplace where they were not welcome.

So we created something called “learning centers” in 1984 and established three South Dallas learning centers that were approved by the court of appeals, and then established some West Dallas learning centers for the Hispanics. And see, the federal judge had control over the pocketbook. They could catch up education, if you will. They had computers before any of the white kids had computers.

Cloutman: We supported the notion to have busing dismissed when learning centers got created and schools got expanded to offer a choice of desegregating options to kids. The loss of public support in parts of town and the fact it took so damn long … nothing that takes that long can not have some wheels falling off the bus, and they did.

Thomas: Busing may have worked in Charlotte, N.C., and it might work in a little town like Mineola, Texas, but the problems are so much bigger in bigger cities.

Johnston: There were school board members at the time who grew to resent the extra amounts of money being spent in other parts of town, but Nolan Estes and Linus Wright, both of their attitudes were: “It’s a court order, we don’t have a choice, we’re going to do it, and we’re going to do it right.” Nolan was a positive person — still is to this day — and I never heard him say a negative word about it, and I was with him for 10 years.

Sanders: There was built, before [Barefoot] had the case, the Skyline magnet school, and there was not a counterpart in South Dallas. And that was the balance, that a second one should be built making it more equal for all the students to be able to opt into those magnets. So that was the origin of Townview [talented and gifted magnet school], and again the DISD drug their feet, and he made clear that he wasn’t going to let go of the case until that was accomplished. He kept hoping he could finish the case and make a final ruling, and then the DISD would do something bad, like the way they would draw their school district lines that were designed to discriminate.

Thomas: If [Barefoot Sanders] wanted to talk to the superintendent, he would call me and say, “Get the superintendent in my office this afternoon. I read all of these quotes in the Dallas Morning News opposing things I have ordered.” And then the next time I met with my client, he would say, “Will you tell the judge to stop reading the Dallas Morning News?”

Sanders: Barefoot was in public life from the time we were married. He was a state legislator, U.S. attorney. I grew up in my adulthood with the idea that we were subject to some hate calls. I just didn’t let it bother me.

People would call the court and say, “Well, you just tell Judge Sanders that I’m never going to vote for him again,” because they’d been a friend and supporter of Barefoot Sanders, not knowing that a federal judge was not elected. [Laughing] He took it as, “They’re going to be disappointed.” He always said, “I’ve got people mad at me on both sides. I guess I must be doing something right.”

Thomas: The lawsuit was filed against the school district and the superintendent and every member of the school board, so all of these individuals were subject to the court jurisdiction, and if you were elected to the school board or hired as the superintendent, you were part of the lawsuit.

We brought in an African American superintendent from Illinois, and he was a nice guy, and his name was Marvin Edwards. He lasted about two years, then he said, “I am going back to Illinois. This is the craziest damn city I’ve ever seen.” He was good, but he didn’t like all of this infighting.

We had a reception over at the [Fair Park] Hall of State to say goodbye and farewell and thanks for being with us, and I went through the receiving line and said, “Thank you, Dr. Edwards. It was a pleasure working with you.”

And he said, “Bob, the first thing I want you to do tomorrow is write to the court and tell them it’s no longer Tasby vs. Edwards. Get my name out of this case.”

Did busing desegregate DISD?

When Barefoot Sanders dismissed the Tasby case in 2003, Dallas ISD had an entirely different demographic makeup — 6 percent white, 31 percent black and 61 percent Hispanic, compared to the respective 54-36-10 percent makeup, in 1971.

Thomas: Did it work? That’s a good question. It complies with the law. The dismissal could have been appealed, but [Sanders] was very careful in writing his order of dismissal and was very well-respected and was a liberal judge, and everybody knew that it had been dismissed by Barefoot Sanders and therefore it was going to stay dismissed. He wrote in his opinion, “I have done my best, but Dallas is a growing city, a changing city, and everything changes.”

Cloutman: It worked moreso than not, of that I’m pretty sure. I say that again from the perspective of the children that we were representing. I don’t think it hurt any white kids any more than they had to get over the first hurdles, the bumps, and that probably did cause a distraction that was unnecessary, but what it did for black kids and brown kids, it required, in a whole lot of detail, the district to do things that otherwise it wouldn’t have done.

Thomas: We’ve had white flight and you can’t force people to stay in schools. There’s Plano, there’s Richardson, there’s Duncanville and DeSoto, so now we’re only 5 percent white and 55 percent Hispanic, and [Sanders] said, “What more can I do? I’ve held onto the white that we do have — Woodrow Wilson is integrated, and to a large extent W.T. White — and that’s all I think can be done.” And now we have to learn with what we have, the reality of life, which is you can’t force people to ride a bus. If they don’t want to ride a bus, they’ll leave.

Protest scene 3 of 3: In protest of the Dallas school board’s consideration to close Woodrow and J.L. Long, students argue that their schools are already integrated, in this Sept. 7, 1975, photo from the collections of the Texas/Dallas History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library.

Johnston: When they talked about “white flight” in that whole period, it was a handy thing to say it was because of desegregation, but a lot of it was demographics — older people buy homes, they age out, die off and new younger ones move in who have kids, so the schools turn over. This just sped up the process.

Cloutman: It is partly economic. If you can’t afford a house in Lakewood, you’re probably not going to live there. But there was a time when [former mayor] Ron Kirk and people like Ron Kirk couldn’t have lived there, and while that has changed some, it hasn’t changed a lot. Dallas is slow to change that.

Johnston: I think it would have happened anyway as people aged in the neighborhood, but at the time, nobody realized that. It kind of reminds me of 20 years ago, Dr. Bill Webster, our chief demographer, said in the year 2010, the district would be majority Hispanic.

Nobody believed it then, but it happened a lot sooner than that. That’s really been the biggest change in the schools — the rapid growth in the Hispanic population. When I first started in the school administration, I think there was probably a 15-20 percent Hispanic population, and now it’s almost 80 percent.

Cloutman: We were the first district in the state to have bilingual education — not because the state required it, but the federal court did. [Desegregation] produced the magnet schools, which are some of the best we’ve ever had academic-wise and art-wise.

Thomas: Some people say we went too fast, some people say we went too slow, but we got to the destination, and desegregation got to be equal opportunity, equal education. It’s clearly the most worthwhile thing I’ve ever been involved in. To shepherd this thing to where it is today, and it ain’t perfect, but it’s peaceful and it’s quiet.

Patton: I’m not going to say it’s gone, but in the realm of most people’s reality, there is no more racism. We used to play poker at Lakewood Country Club with these 30-year-old guys, and they don’t even know what racism is, so it’s a dying breed.

I tell people it’s kind of like going fishing: There’s never been a person born a racist, never been a person born a fisherman. Somebody had to teach him to fish, and somebody had to teach him to hate.

So if it’s dying out, there won’t be no more rookies.