Woodrow Wilson High School opened Sept. 14, 1928, with the first class of seniors graduating the following year. For the next 90 years, countless students, including Dallas Arboretum President Mary Brinegar and Steve Miller of the Steve Miller Band, have walked through the building that is a Texas Historic Landmark. Now, it’s time to party. The Woodrow Wilson Alumni Association is commemorating 90 years of Woodrow with a weekend of events Oct. 24-26. Celebrate the milestone at the homecoming game, then stay for the hall of fame induction ceremony and tours of the new addition.

Woodrow Wilson High School opened Sept. 14, 1928, with the first class of seniors graduating the following year. For the next 90 years, countless students, including Dallas Arboretum President Mary Brinegar and Steve Miller of the Steve Miller Band, have walked through the building that is a Texas Historic Landmark. Now, it’s time to party. The Woodrow Wilson Alumni Association is commemorating 90 years of Woodrow with a weekend of events Oct. 24-26. Celebrate the milestone at the homecoming game, then stay for the hall of fame induction ceremony and tours of the new addition.

You got pranked as a first-year student.

Hazing isn’t tolerated at Woodrow, but students through the years can’t seem to resist playing a few harmless pranks on underclassmen. During the 1950s, all new male students had to roll their pants above their knees after lunch. “We all felt dumb for doing it, but it was all in good fun,” says “Blazing Saddles” actor Burton Gilliam, who graduated in 1956. “They wouldn’t put up with it today.” By the 1970s, the wholesome pranks of the past turned entrepreneurial, and the seniors charged the freshmen tickets to use the elevator. “Of course you couldn’t use them, but freshmen had no idea it was a prank,” says 1976 graduate Michelle Bobadilla, senior associate vice president of outreach at the University of Texas-Arlington. “Luckily, I had a sister who graduated in 1970 and warned me about it.”

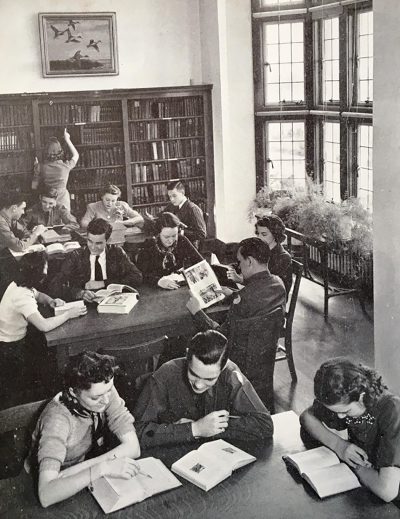

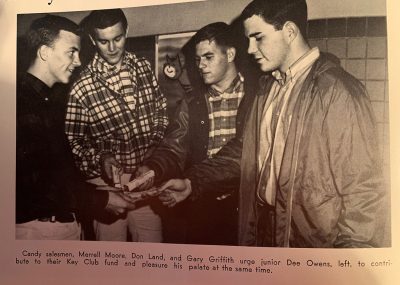

You had club day.

Wouldn’t it be great if extracurricular clubs met during school hours? In the 1950s, they did. Every other week, students spent first period meeting with their clubs. There were history, political and environmental clubs, but they weren’t all scholastic. “I was a member of the Canasta club. It was a card game,” Gilliam says. “Everyone looked forward to it.”

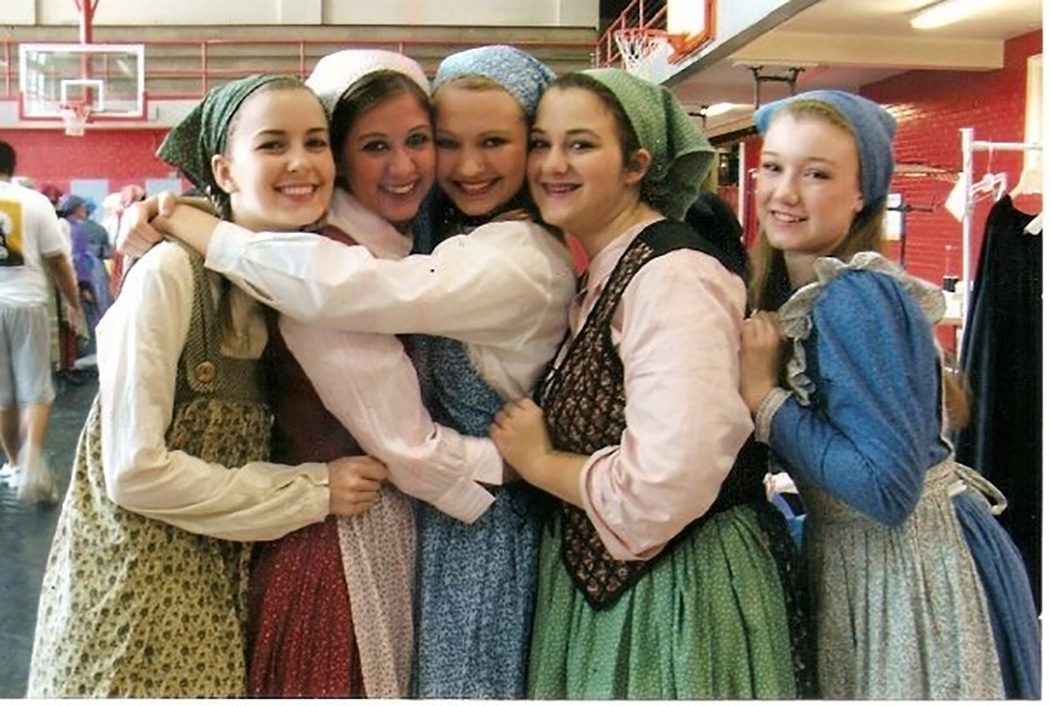

You were involved in the musical.

The first musical production was in 1943, and the tradition has continued ever since. Woodrow doesn’t produce your typical high school musical. In 1994, the “Singin’ in the Rain” show featured a shower that poured water on the cast. And in 1998, monkeys flew in “The Wizard of Oz” thanks to professional stage-flight equipment rented from Las Vegas. Although students are the ones who spend months rehearsing, moms help with costumes while dads build the set and serve as stagehands in a group called “Men in Black.”

You know what’s written above the auditorium stage.

The unofficial chronicles of the Woodrow Wilson musicals are located high above the stage. Since the 1970s, students in the show have climbed the catwalk to write their names and graduating years on the wall. The practice is no longer encouraged because of safety reasons, so students have taken to writing their names in closets around the stage. But a few daring students still sneak up to the catwalk to keep the tradition alive. “Yep, I did that,” says Katie Anderson, a 2009 graduate and the former Woodrow musical director. “It’s like putting your name next to a famous person. These kids have been going to the musicals since they were 5, so they know the stars and want their name next to theirs.”

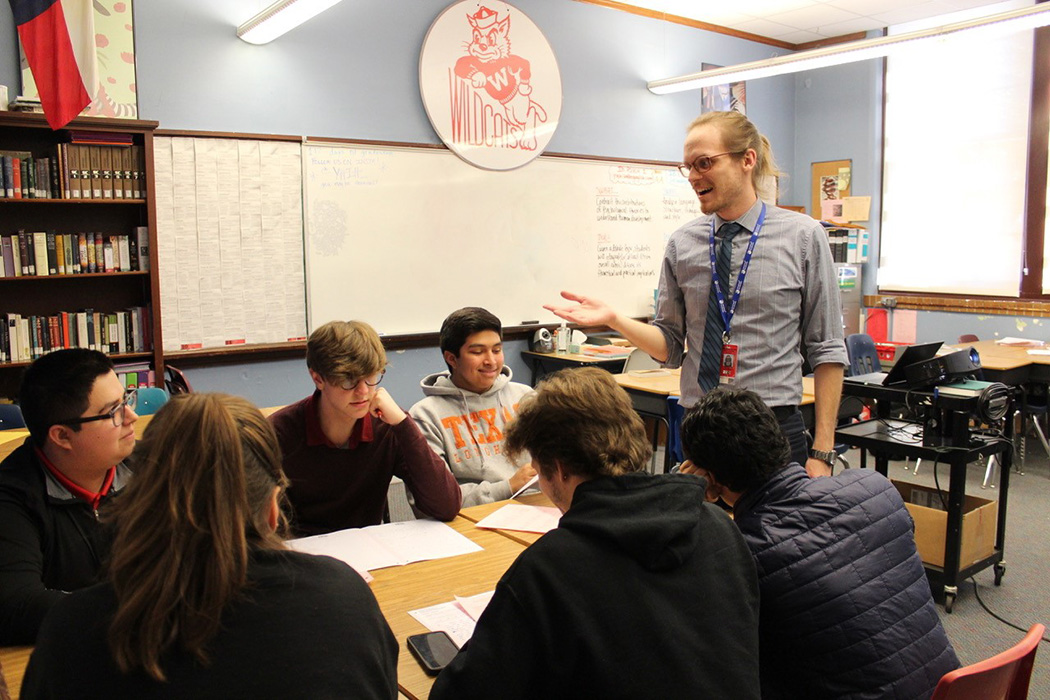

You’re involved in the IB program.

Woodrow is the only Dallas ISD school with graduates in the globally focused International Baccalaureate program. Ruth Vail, a 1991 graduate, spearheaded the implementation of the program when she returned to the school as principal in 2005. She rallied the community, parents and alumni, and together, they raised $25,000 to cover the program’s authorization costs and annual fee. “I always thank the outside community for helping,” Vail says. “Asking DISD, it would have never happened. I tried to make sure students could benefit from a public school. You don’t have to pay $30,000 for a private school.” Since the first class graduated in 2015, enrollment in the program has grown to 150 students, and their test scores have surpassed the national average.

You know about the slice of cake.

For nearly a century, a tasty morsel has been entombed in the foundation. The slice of cake from the 1913 wedding of President Woodrow Wilson’s daughter was sent by a Texas bridesmaid to her cousin in Dallas. In 1927, the slice was laid in one of the school’s cornerstones. How the cake was preserved for 14 years before it was buried in the foundation is anyone’s guess.

Multiple generations have attended the school.

Constable Michael Orozco graduated from Woodrow in 1991, his son graduated from the IB program in 2017 and his daughter will graduate in the class of 2023. “Everyone at Woodrow will tell you it’s such a special school because it’s like one big family,” he says. “Many of the alumni want their sons or daughters to attend so they can have the same experiences.” Generations of alumni share his story. For a decade, Bobadilla says at least one of her family members attended Woodrow. “My sister was homecoming queen. My brother was on the football team,” she says. “It gave you a sense of community. We felt grounded and rooted in our school.”

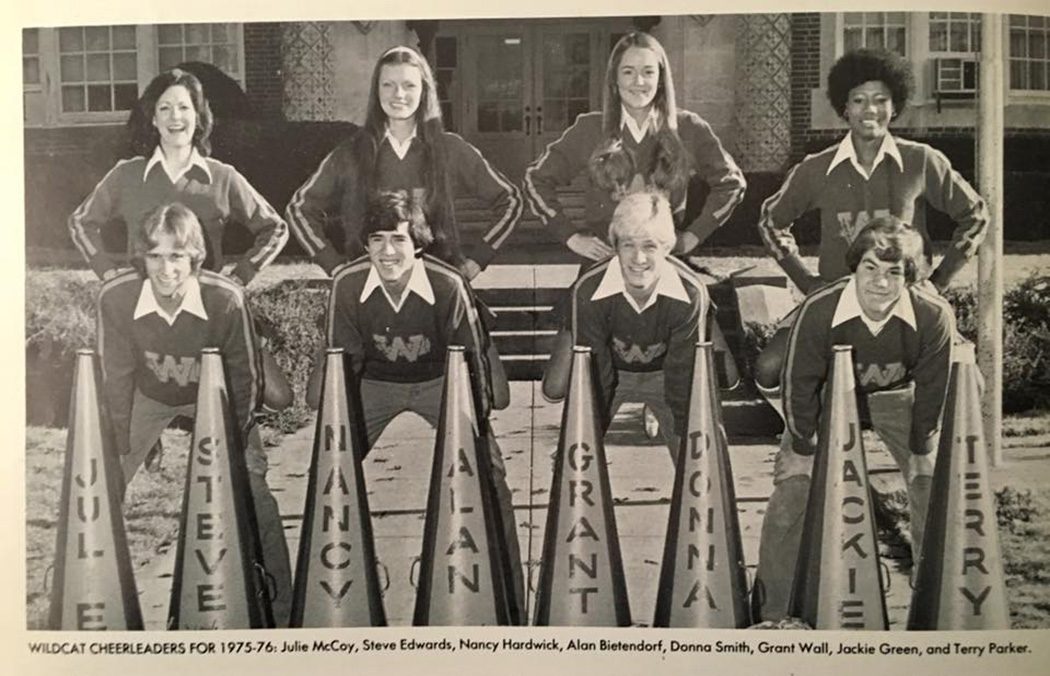

You have Wildcat pride.

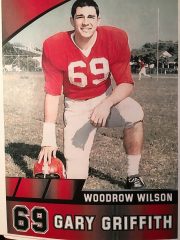

There’s nothing like high school football in Texas. And at Woodrow, the tradition of athletic excellence runs deep. It is the only public high school in the country to produce two Heisman Trophy winners in Notre Dame wide receiver Tim Brown and Texas Christian University quarterback Davey O’Brien. Throughout the years, students have looked forward to Friday pep rallies, where the Sweethearts dressed in gray and red cheer their team to victory. Under the lights of the stadium, fans yell the familiar cheers. “The seniors still yell S-E-N-I-O-R-S, seniors are the best,” Anderson says. That Wildcat pride remains, even after heartbreaking defeats. When 1966 graduate Gary Griffith attended Woodrow, his undefeated team lost to rival Hillcrest. “We had visions of moving on and playing in the state final, but it was a reminder that things don’t always turn out the way you want,” Griffith says. “You can’t take anything for granted as a team and a school. It was a nice reminder for life. There are setbacks, but we were taught at Woodrow how to meet those challenges.”

You were in the largest ROTC group in the USA.

In the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, Woodrow had the largest Junior ROTC program in the country with 16 different companies and an ROTC band. Every Wednesday morning, cadets marched in an ROTC parade. “It was a way of life at Woodrow,” Gilliam says. “I took it to heart. It required body and soul.”

You were Student of the Week.

Each week, an outstanding student was recognized with a segment on the local news. But nothing stands in the way of students and their caffeine. “It was a Friday, and my friend and I decided to go get coffee,” Vail says. “I was Student of the Week, and when I came back, the principal was mad. He said the TV people were looking for me. With no cell phones, they couldn’t text me.”

You give back.

You give back.

One of the best ways to stay connected to Woodrow is to give back, Griffith says. The former Dallas City Council member and his classmates founded the Land-Hyland Scholarship Fund, which has given more than $60,000 to student-athletes in honor of two football players who died. And in October, Griffith’s class will unveil a marble stone plaza dedicated to Wildcat legends. Community members can purchase stones engraved with the names of hall of fame members. All proceeds go toward school projects. “Woodrow prepared me in a number of ways to be a volunteer in the community,” he says. “I’m a small story, but the big story is what you learn about community service and civic responsibility.”

Your slogan was, “Woodrow…Enough said.”

Your slogan was, “Woodrow…Enough said.”

Leigh Ann Stovall O’Quinn was brainstorming ideas for a cheer squad fundraiser when she saw a sorority bumper sticker that sparked her imagination. She went to her grandmother, a 1936 graduate who owned a decal business, and created the slogan, “Woodrow…Enough said.” The saying spread throughout the class of 1991, and the decals, which featured red bubble letters on a gray background, can still be seen on a few cars in the neighborhood. “When people ask where you went to high school, you don’t say Woodrow Wilson,” O’Quinn’s classmate Orozco says. “You say Woodrow. You don’t need to say anything else. Enough said.”